Preface

Sharmilas real contribution lies in her drawing the critical feminist discourse (that normally remains confined to the portals of university departments and their facultyseminars and workshops) into the dalit movement and the feminist movement. Sharmila untiringly endeavoured to avoid the ghettoisation of the dalit and gender questions and to get the satyashodhak agenda into the mainstream of social science discourse. Pratima Pardeshi , Loksatta

In this volume, Sharmila Rege provides us a theoretically advanced interpretation of Babasahebs thinking on the interstices of the caste and feminist questions. Reges work assumes significance especially in the context of limited engagement with caste in mainstream feminism. Gopal Guru , Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University

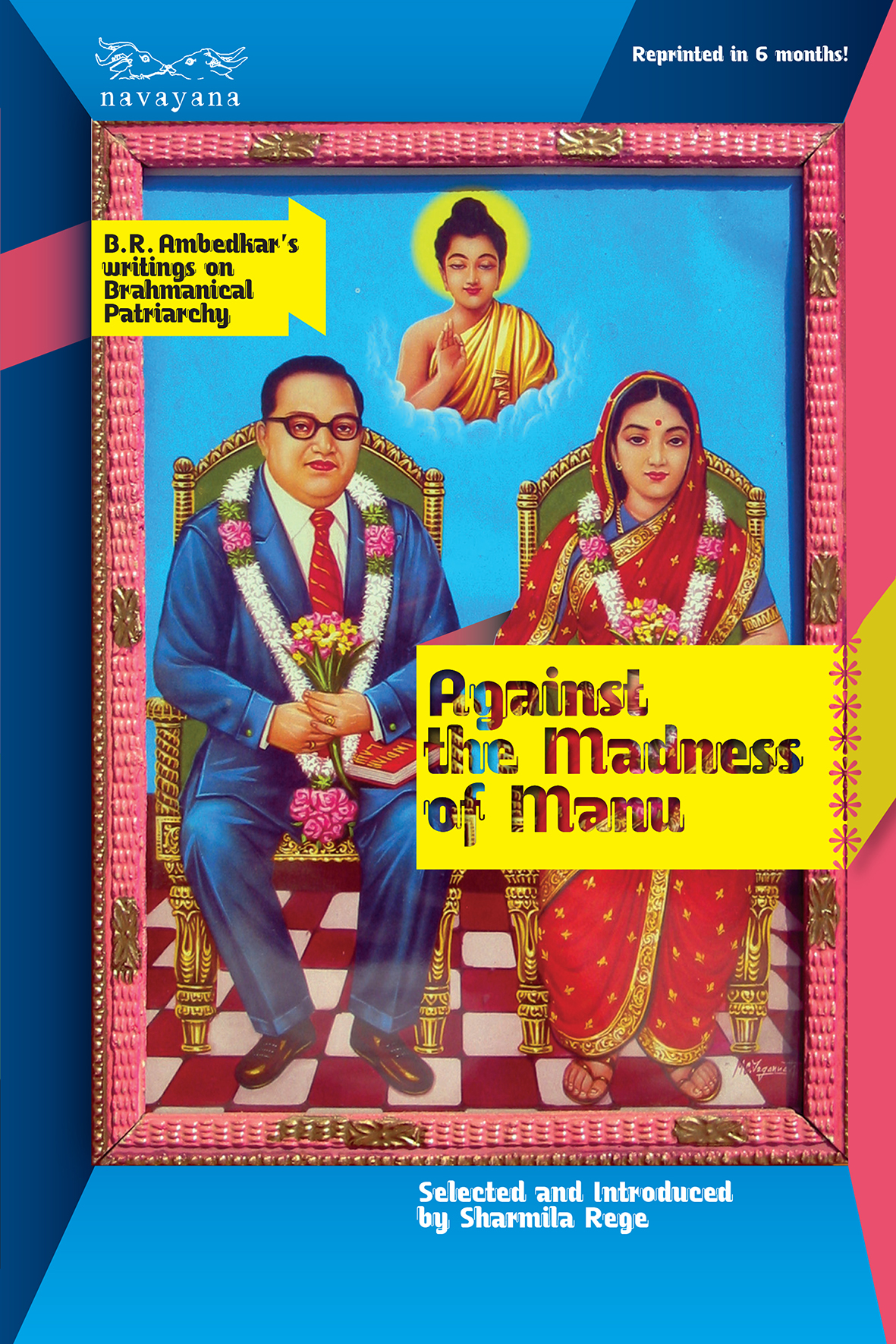

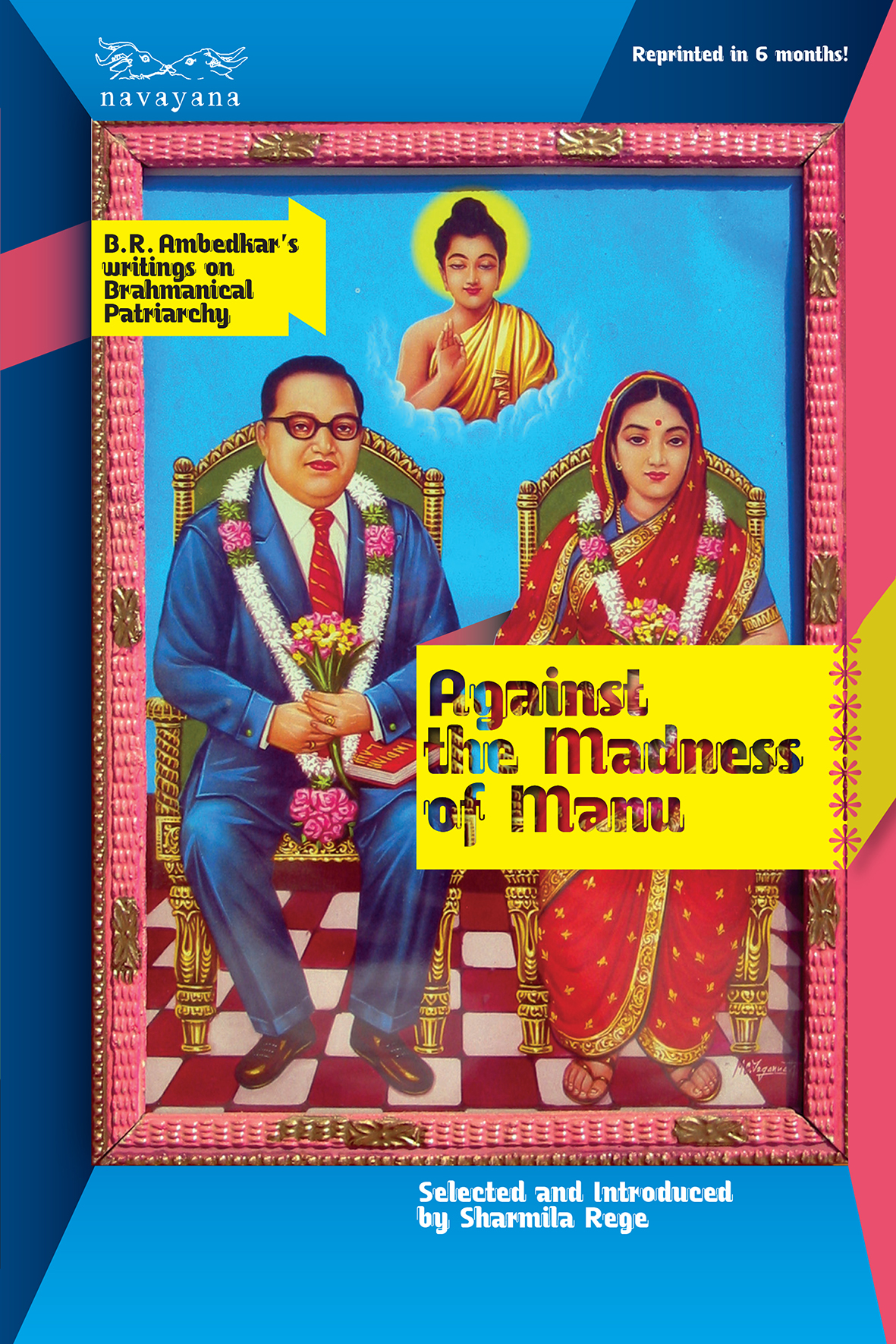

Against the Madness of Manu compiles a vast number of Ambedkars writings on gender and caste. Each of his lengthy expositions is accompanied by original contextual introductions as well as summaries by Professor Rege, leaving the reader with the tools by which to link caste with gender, and to reclaim Ambedkars works as feminist classics on Brahmanical patriarchy... Reges hallmark talent in reading popular cultural sources shines through. For many years she has been collecting and unpacking the vast outpouring of poems, songs and artworks produced amongst Ambedkarite communities, and bringing these materials to a wider world. Shefali Chandra , Seminar

A brilliant and timely intervention in feminist scholarship in India, Dalit studies, legal sociology, and the sociology of caste. Kamala Visweswaran , author of Un/Common Cultures

Through her work on caste, and the issues she raised, she forced metropolitan feminists to first read and then think about caste before they jumped in to take positions on controversial issues generated all around us. Uma Chakravarti , historian

This book is for

Pappa for making Babasaheb my childhood hero through the memories of his early years at Siddharth College;

Ambedkarite shahirs and gayan parties , scholars and activists of the PhuleAmbedkarite movement for introducing me to the life and work of Babasaheb and its many interpretations;

and students at the University of Pune doing courses on Dalits and the Public Sphere, and Gender and Caste: History and Memory for making me believe that I could do this book.

Publisher's note

All references to Dr B.R. Ambedkars writings and speeches, unless stated otherwise, are from the series Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches ( BAWS ), published by the Education Department, Government of Maharashtra, Mumbai. Copyright permission has been obtained from Prakash Ambedkar, grandson of Dr B.R. Ambedkar.

Since Ambedkars work has been published by various publishers over decades (between 1917 and 1956), and many times posthumously, there is inconsistency in spelling and usage even within the BAWS volumes. In this edition, we have standardised the spellings since this does not detract from the import. (Where both Sudra or Shudra have been used we have stuck to Shudra; where Brahman and Brahmin are used, we have stuck to Brahman.) Since Dr Ambedkar in general seems to have preferred capitalising caste terms such as Brahman, Mahar or Shudra, this has been retained.

Dr Ambedkars work has not been edited or rearranged, except for the odd article or two inserted for readability. Jumps in the text, if any, have been indicated with ellipses or explained in the notes.

In the case of Castes in India, we have followed the original Indian Antiquary (1917) edition of the text, and have numbered the paragraphs.

Dr Ambedkars original footnotes have been retained within square parentheses. Additional notes and annotations have been provided by the publisher in consultation with this volumes editor, Sharmila Rege.

IntroductionTowards a Feminist Reclamation of Dr Bhimrao Ramnji Ambedkar

IN INDIAN UNIVERSITIES today, it is not often that we encounter the writings of Dr B.R. Ambedkar in the curricula of social sciences and humanities. It seems appalling that students and teachers, like myself, can in most cases sail through postgraduate and research degrees in social sciences, and practise womens studies in the academia without ever having read the writings and speeches of Ambedkar. Since the late 1990s, this picture is changing as Dalit scholars in the academy have been integrating the writings of Ambedkar in sociology, political science, cultural studies and literary studies curricula. I begin on this self-reflexive note to highlight the manufacture of ignorance in our institutions of higher education and ways in which one is complicit through the privileges of caste and education. This is also to place on record my debt to teachers in the PhuleAmbedkarite movement; activists, writers, shahirs (bards) and gayan parties (musical troupes) whose work continues to introduce me and others to the writings and works of Ambedkar and to the varied ways of interpreting them.

It is against this backdrop that this reader focuses on Ambedkars writings on Brahmanical or graded patriarchya term that feminist scholar Uma Chakravarti first used in 1993. It seeks to drive home the urgency of a feminist turn to Ambedkar by drawing attention to three seemingly disjunctive instances from the political past and present. Each of these instances projects a distinct relation between caste and gender, albeit on sites disparate in time and space. The first site refers to Brahman Parishads (Conference of Brahmans), both imagined and real. The second concerns a dialogue between non-Dalit and Dalit feminists. The third is about the rhetoric of rape and compensation for Dalit women in contemporary state politics.

In the first instance, let us consider resolutions three and four in The Brahman Parishad of 1950, a text set in the imaginary future, written by Dinkarao Javalkar, one of the best known leaders of the non-Brahman movement in Maharashtra in the 1920s. Javalkar outlines the fictitious resolutions of the Brahman Conference:

Many cases of Brahman women beating up their husbands are being registered in court. Hence a law must be made to protect the Brahman husband I feel ashamed to tell you that in their blind imitation of the Europeans, Brahman women smoke, perform in theatres, and shave in salons. In fact, the entire Bavankhani [the red light area dating to the Peshwa period] is full of Brahman womenone Brahman prostitute has even put up a board declaring herself to be a Peshwa pedigree (Phadke 1984: 149; translation mine ).

Javalkar, writing in the wake of B.G. Tilaks fierce opposition to a Bill introduced by Vithalbhai Patel in 1918 to legalise inter-caste marriages, describes Brahman women of the 1950s as husband-beaters, smokers, and prostitutes entering into mixed marriages with non-Brahman men. The Brahman men, no longer capable of controlling their women, are thus reduced to women with moustaches (ibid., 148). More than fifty years after the projected period of the imagined Parishad, the Multilingual Brahman Mega Convention organised in Pune in 2009 resolved that in order to protect the purity of the Brahman community and in the larger interest of the country, all brothers and sisters of the community should give priority to marriage within the community itself.

Further, the same mega convention, in a published code of conduct for Brahmans for the changing times, spelt out a dress code for women and stressed their duties to the family and community. This points not only to the unrelenting anxiety over mixed marriages in caste society but also to a paradoxical continuity between contemporary elite reactions and early twentieth-century non-Brahman assertions that sexualised Brahman women. However, this ridicule of Brahman women emerged from the non-Brahman publics which placed the central opposition in society as being between the virtuous Hindus and the non-virtuous Brahman. In this, the non-Brahman publics were departing from Jotirao Phules (182790) position. For Phule, the primary opposition was between Shudra, Atishudra and women on the one hand and ShetjiBhatji (moneylenderspriests) on the other, and thus his critique of the ideology of caste radically reconceptualises gender codes too. While the Brahman convention in contemporary Pune reasserts faith in endogamy for national interest, and imposes new codes on Brahman women, non-Brahman intellectuals of the early decades of the twentieth century sexualised the western modernity of Brahman women and rendered non-Brahman patriarchies invisible.

Next page