When he speaks in public he is galvanic, creative, and almost embarrassingly to the point. To compare the average oration of a Congress politician with a speech by Doctor Ambedkar is like comparing a Hindu chant with a fusillade of pistol shots

Beverley Nichols , British writer, in 1944

Dr Ambedkars warnings on caste and religion dictating terms to democracy have been ignored at peril. We are in a crisis. His speeches here show us a way out

Prof Sukhadeo Thorat , Indian Institute of Dalit Studies

What a steam-roller intellect: irresistible, indomitable, unconquerable, levelling down tall palms and short poppies: whatever he felt to be right he stood by, regardless of consequences

Dr Pattabhi Sitaramayya , member, Constituent Assembly

There are no more worlds for him to conquer

Prof Herbert Foxwell , London School of Economics, in 1916

The value of Ambedkars contribution lies in objective recitation of the facts and the impartial analysis of the interesting development that has taken place in his native country. The lessons are applicable to other countries as well; nowhere, to my knowledge, has such a detailed study of the underlying principles been made

Prof Edward Seligman , Columbia University, 18911931

There is certainty of complete success in regard to anything which he knows himself fit to undertake

Prof Edwin Cannan , London School of Economics

One of Indias leading citizens, a great social reformer and a valiant upholder of human rights

Grayson L. Kirk , President of Columbia University, in 1952

A Stake in the Nation: Selected Speeches

B.R. Ambedkar

E-ISBN 9788194447160

Published June 2020

Introduction, Anurag Bhaskar

this edition and annotations, Navayana Publishing Pvt Ltd 2020

Selections, Bhagwan Das

First Published by Bheem Patrika, Jalandhar in 1963 as

Thus Spoke Ambedkar: Volume 1

Published in 2010 by Navayana as

Thus Spoke Ambedkar: A Stake in the Nation, Vol 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Navayana Publishing Pvt Ltd

155 2nd Floor, Shahpur Jat, New Delhi 110049

Phone: +91-11-26494795

navayana.org

Subscribe to updates at navayana.org/subscribe

Follow on facebook.com/Navayana

Distributed in South Asia by HarperCollins India

A Stake in the Nation

SELECTED SPEECHES

B.R. Ambedkar

edited by

Bhagwan Das

introduced by

Anurag Bhaskar

annotated by

S. Anand

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (18911956) was a radical thinker, statesman, lawyer, editor of newspapers, author of many books, economist, jurist, philosopher, and founder of a school of Buddhism. Born into an Untouchable Mahar family in Mhow in present-day Madhya Pradesh, he waged a relentless, lifelong struggle for the rights of Dalits. Having earned doctorates from both Columbia University and the London School of Economics, he went on to serve as Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Indian Constitution. Ambedkar converted to Buddhism along with half a million followers a few months before his death in 1956.

Bhagwan Das (19272010) was an Ambedkarite and a historian of the dalit movement. After serving in the Royal Indian Air Force as a radar operator during World War II, a meeting with Ambedkar in Shimla, in 1943, defined the trajectory of his lifea single-minded pursuit of Babasahebs ideals. Das worked with Ambedkar as a research assistant in 195556. Among his several books are the four volumes of Ambedkars speeches that he selected, edited and published in the series Thus Spoke Ambedkar beginning in 1963. The speeches featured in A Stake in the Nation are taken from the first volume of this series. Supported by a coalition of dalit organisations, Das testified against untouchability in 1983 before the UN Subcommission on Human Rights in Geneva, much to the chagrin of Indias official delegation at the conference. He is the author of In Pursuit of Ambedkar: A Memoir (2010) where he writes of how his father spoke of Ambedkar as Ummeedkar, the Harbinger of Hope ( ummeed ).

Anurag Bhaskar teaches at Jindal Global Law School, Sonipat. He is an Affiliated Faculty of the Center on the Legal Profession at Harvard Law School, and a Visiting Faculty at Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, Delhi. He holds a Masters in Law degree (2019) from Harvard Law School.

Contents

When Justice Y.V. Chandrachud, the former Chief Justice of India, was a young lawyer, he would often go to a caf called The Wayside Inn in Kala Ghoda, Bombay. One of the commonest sights there was a man who spent the entire afternoon writing and making notes. It was Dr B.R. Ambedkar. At the time, he was making copious notes for the future constitution of India. In a life spanning polities, milieus and countries, this was a familiar sightAmbedkar writing, thinking.

In a manner, Ambedkar was archiving his own thoughts for a future generation; as if he did not want thinking itself to end. He did not want how and what he thought to die with him (Das 2010, 61). Despite his failing health in 1956, by the end of which year he would pass away, he spent all day researching and writing, while also planning the future course of public action. An expert of economics, political science, law, and administration, Ambedkar propounded his thought through speeches, invariably momentous, and writings, some self-published, and several left behind as manuscripts. But his ideas were never considered mainstream.

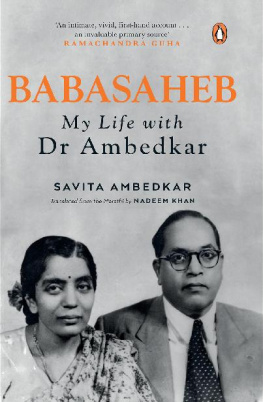

The late Bhagwan Das, editor of this collection and a former research associate of Ambedkars, notes: In spite of [Ambedkars] encyclopedic learning, his humanity, his patriotism and his unimpeachable integrity, there was no Indian more maligned, misrepresented and vilified publicly and privately by his own countrymen (p. 31). In his life, Ambedkar was called an anti-national, a traitor and a British stooge. Cartoons in most newspapers largely upheld these prejudices (Syama Sundar 2019). The apathy and vilification continued after his death. Eleven years after his passing, in 1967, his private papers were initially dumped in an open yard after his wife Savita was evicted from the Alipur Road bungalow that had been the rented home of the Ambedkars in Delhi. Arun Shourie, who used his editorship of the Indian Express to mount a campaign against the Mandal Commission and the very idea of reservation, wrote an entire book in 1997 to portray Babasaheb as a self-centered, unpatriotic, power-hungry anti-national. Many liberals secretly admired Shourie then, and today he is a liberal darling for criticizing the Modi-led iteration of the Bharatiya Janata Party. Despite all these hurdles and a serious lack of resources, and against consistent denigration, Dalits have kept alive powerful memories of their hero. For them, he has always been Ummeedkar, the one who brings hope, as Bhagwan Das fondly remembers his father speaking of him (Das 2010, 21). Ambedkar, however, has become more relevant today for everyone than he ever was. Once known for the record number of statues built in his honour, he has now become the most quotable figures. Judges, opposition leaders, liberals, feminists, and even the social conservative forces he so despised, clamour to make known their adoration for him. Yet he remains a figure who cannot be squarely placed in any one conceptual category.