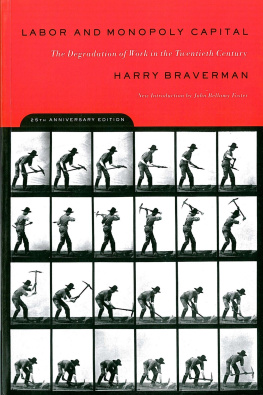

Labor and Monopoly Capital 25th Anniversary Edition

Labor and Monopoly Capital

The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century

Harry Braverman

25th Anniversary Edition

Foreword by Paul M. Sweezy

New Introduction by John Bellamy Foster

New Edition Copyright 1998 by Monthly Review Press

Copyright 1974 by Harry Braverman

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Braverman, Harry.

Labor and monopoly capital : the degradation of work in the

twentieth century / by Harry Braverman; foreword by Paul M. Sweezy

: new introduction by John Bellamy Foster.25th anniversary ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-85345-940-1 (pbk.)

1. LaborHistory20 century. 2. CapitalismHistory20th

century. 6. Working classHistory20th century.

I. Title.

HD4851.B66

331.0904dc21

98-46497

CIP

Monthly Review Press

122 West 27th Street

New York NY 10001

Manufactured in Canada

10 9 8 7 6

Acknowledgments

To the following, for permission to reproduce short passages from the works named: Oxford University Press, from White Collar by C. Wright Mills, copyright 1951 by Oxford University Press; Division of Research of Harvard Business School, from Automation and Management by James Bright, copyright 1958 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College; University of Minnesota Press, from The Sociology of Work by Theodore Caplow, copyright 1954 by the University of Minnesota; Harvard Business Review, from Does Automation Raise Skill Requirements? by James Bright, July-August 1958, copyright 1958 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College; Columbia University Press, from Women and Work in America by Robert W. Smuts, copyright 1959 by Columbia University Press; Public Affairs Press, from Automation in the Office by Ida R. Hoos.

Contents

Introduction to the New Edition

John Bellamy Foster

Work, in todays society, is a mystery. No other realm of social existence is so obscured in mist, so zealously concealed from view (no admittance except on business) by the prevailing ideology. Within so-called popular culturethe world of TV and films, commodities and advertisingsconsumption occupies center stage, while the more fundamental reality of work recedes into the background, seldom depicted in any detail, and then usually in romanticized forms. The harsh experiences of those forced to earn their living by endless conformity to boring machine-regulated routines, divorced from their own creative potentialall in the name of efficiency and profitsseem always just beyond the eye of the camera, forever out of sight.

In social science, the situation is hardly better. The dismal performance of legions of orthodox economists and sociologists in the area of work is testimony to the dominance of ideological imperatives within mainstream social science, despite its scientific pretensions. There is no other realm requiring as much concealment to permit the continued dominance of capitalist relations of production. What must remain impenetrable is not so much the stultifying character of modern working life: that is hard to deny in a time when the neologism McJob has entered the language to describe a form of employment experienced by millions. The secret is the prevailing social orders systematic tendency to create unsatisfying work.

Orthodox economists have consistently steered clear of issues of production and the organization of work, viewing these from the distant standpoint of the exigencies of the market (the buying and selling of factors of production). They almost never engage directly with the realm of production itself, in which capital and labor struggle over the control of working time and the appropriation of surplus productissues discretely left to those concerned with the everyday practical realities of business and management. As the heterodox economist Robert Heilbroner has written, The actual social process of productionthe flesh and blood act of work, the relationships of sub- and superordination by which work is organized and controlledare almost strangers to the conventional economist.

Sociologists, it is true, have analyzed occupational reality, looking for signs of alienation. But sociology, like economics, has usually been divorced from any real understanding of the way in which working life is objectively organized around the division of labor and profitability. All too often academic investigators have assumed that the essence of working life is to be discovered simply in the subjective responses of scientifically selected samples of workers to carefully constructed questionnaires. Even radical theorists, familiar with the results of such economic and sociological research but lacking direct experience of their own with the capitalist labor process, have frequently fallen prey to illusions generated in this way, as Paul Sweezy eloquently explains in his foreword to the present volume.

When it was published in 1974, Harry Bravermans Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century immediately stood out among twentieth-century studies in the degree to which it penetrated the hidden abode of the workplace, providing the first clear, critical understanding in more than a century of the labor process as a whole within capitalist society. It thus opened the way to the flood of radical investigations of the labor process that followed. Bravermans success, where so many others had failed, was not simply fortuitous. Much of the basis for his achievement is to be found in his personal background.

Braverman was born on December 9, 1920, in New York City, the son of Morris Braverman, a shoeworker, and Sarah Wolf Braverman. Caught up in the fervent radical intellectual spirit of the Depression years, he aspired to a college education and enrolled at Brooklyn College, only to be forced to terminate his schooling within a year due to the hard economic times. Beginning in 1937, Braverman apprenticed at the Brooklyn Naval Shipyard, where he began as a coppersmith, branched out into pipefitting, and eventually supervised a team of eighteen to twenty workers at refitting pipes of docked ships. Drafted near the end of the war in 1945, he was sent by the Army to Cheyenne, Wyoming, where as a sergeant he taught and supervised locomotive pipefitting. In 1947, he and his wife Miriam settled in Youngstown, Ohio, where he worked in steel layout and fitting at Republic Steel (where he was quickly fired at the instigation of the FBI), William B. Pollock Co., and Owen Structural Steel.

From his teenage years in Brooklyn on, Braverman had identified with socialism, participating first in the Young Peoples Socialist League and later in the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), as part of a small but vibrant Trotskyist movement. During the 1940s and early 1950s, he wrote frequently for various SWP publications under a party name, Harry Frankel. But in 1953, Braverman broke with the SWP and left his job in the steel industry to establish, along with Bert Cochran, a new independent periodical, The American Socialist, which lasted until 1960. Bravermans editorial experience on The American Socialist opened the way to a new career from 1960 to 1967 as editor and later vice president and general manager at Grove Press, where he was credited with publishing The Autobiography of Malcolm X. During his Grove years, he picked up a B.A. at the New School for Social Research. In 1967, he became director of Monthly Review Press, a position he held until his death on August 2, 1976.

Next page