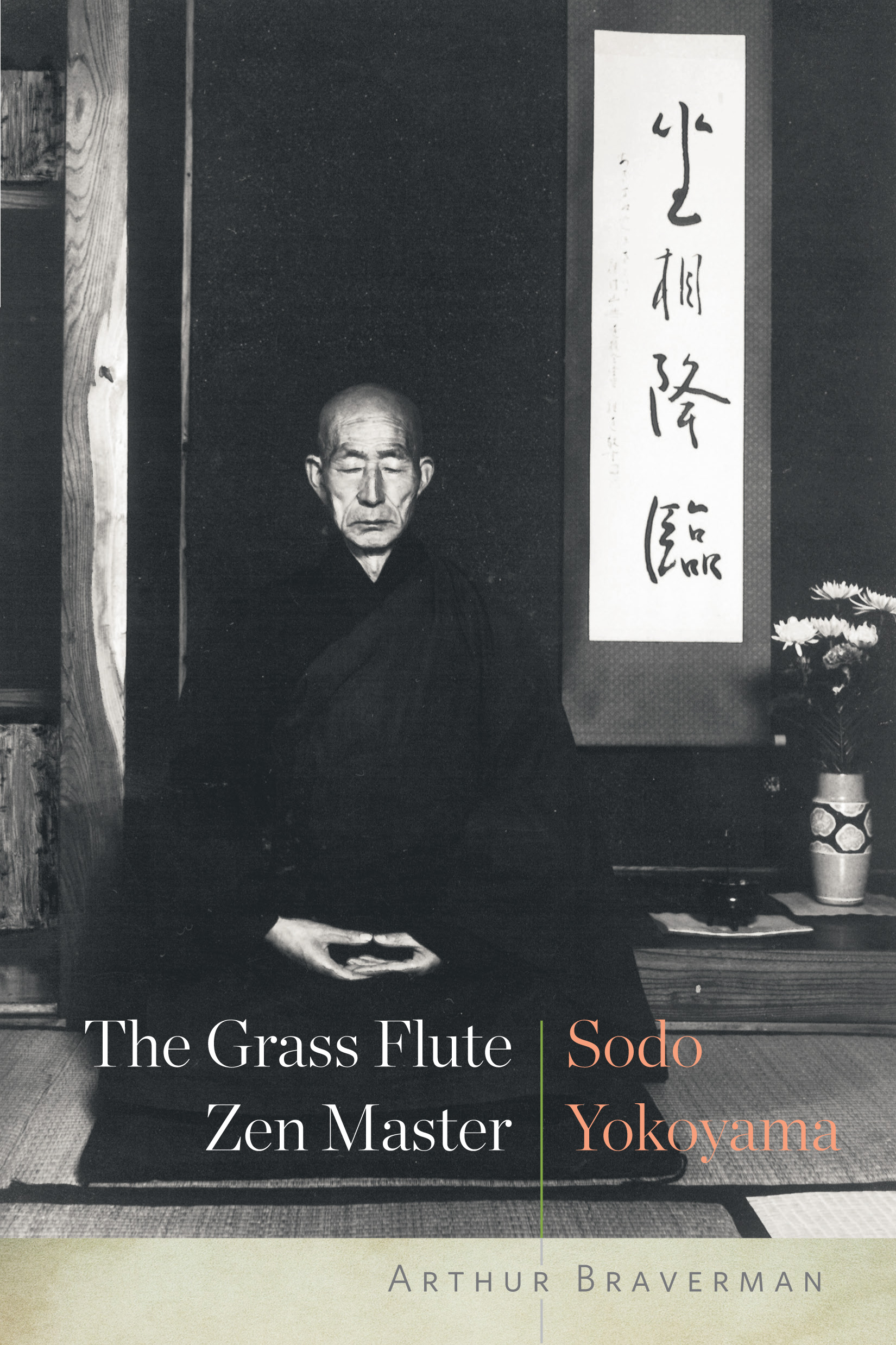

THE GRASS FLUTE ZEN MASTER

A LSO BY A RTHUR B RAVERMAN

Translations:

Mud and Water: A Collection of Talks

by Zen Master Bassui

Warrior of Zen: The Diamond-hard

Wisdom of Suzuki Shosan

A Quiet Room:

The Poetry of Zen Master Jakushitsu

Non Fiction:

Living and Dying in Zazen

Fiction:

Dharma Brothers: Kodo and Tokujo

Bronx Park: A Pelham Parkway Tale

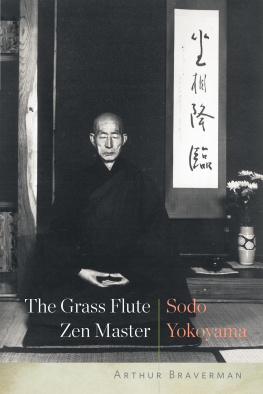

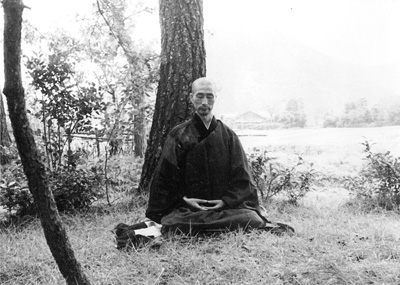

Opposite: Yokoyama playing the grass flute at Kaikoen Park

Copyright 2017 by Arthur Braverman

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Cover and Interior design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

eISBN 978-1-61902-892-0

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Ari, Oliver and Sanae:

The next generation

Contents

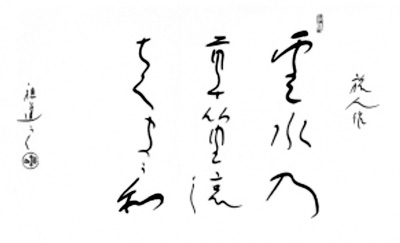

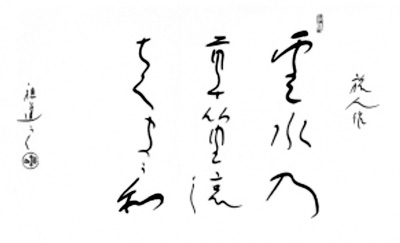

unsui no

kusabue kanashi

chikuma gawa

Floating cloud monk

Plays leaf whistle soulfully

Chikuma River

Written by a traveler

(from Living and Dying in Zazen )

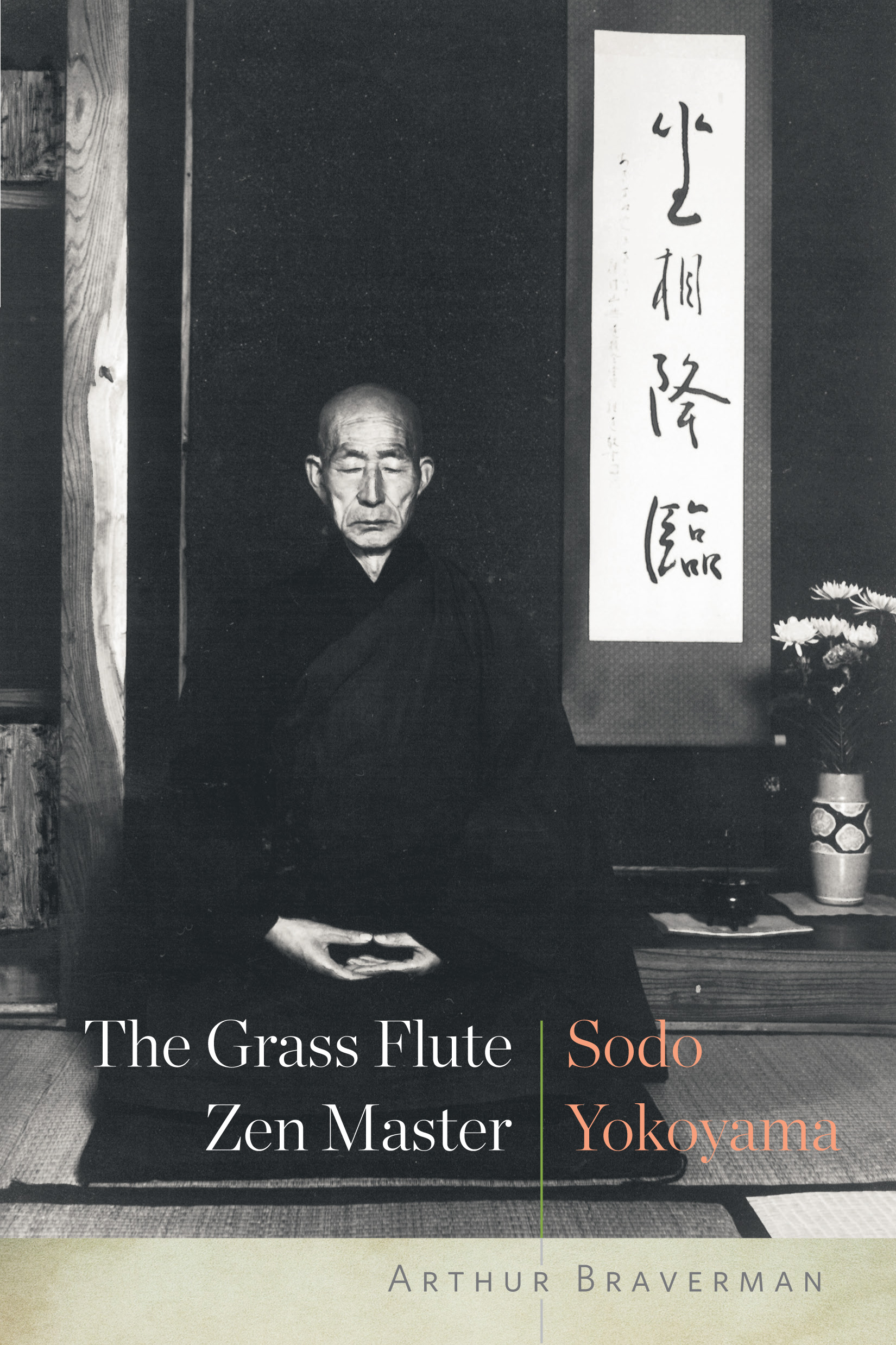

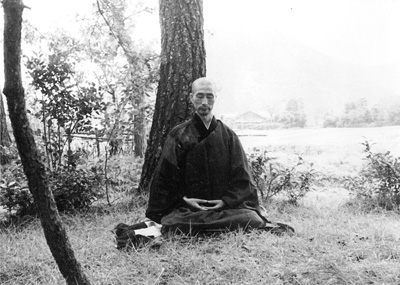

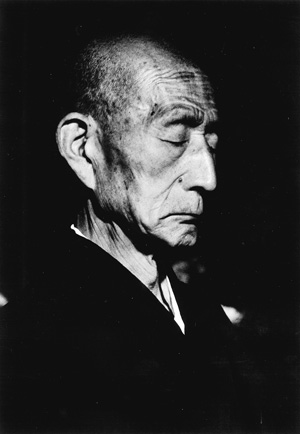

Sodo Yokoyama practicing zazen

1

In Search of a Japanese Maharshi

I step outside of the Komoro Train Station into the afternoon sunan unusually dry sunny day for early June in central Japan. The year is 2014. The station is approximately fifty yards from the entrance to Kaikoen Park, where Sodo Yokoyama spent more than twenty years meditating, playing the leaf flute, and brushing beautiful calligraphy.

Ive come here to meet Joko Shibata, Yokoyamas sole disciple. Joko and I have become friends since my first interview with him in 1996. I try to visit him whenever I come to Japan. Our connection, of course, is Jokos late teacher, the hermit of Kaikoen Park, Sodo-san, as he is familiarly called. Im trying to learn more about this colorful Zen man who spent the last twenty-two years of his life demonstrating to Japanese who happen to be strolling through the park what it means to be forever young.

As I sit on a rickety wooden bench outside the station waiting for Joko, I reflect on my first encounter with the Grass Flute Zen Master. It was autumn 1970. Together with two friends from Antaiji Temple, Steve and Lew, I came to meet this unique Zen man Id so often heard about. At the time my knowledge of Sodo-san was a mixture of fact and myth.

Theres a monk named Sodo-san, a brother disciple of Uchiyamas, who lives in the woods in Nagano Prefecture. He spends his days sitting in zazen, brushing poems, and playing music on a leaf, Lew said.

The image appealed to both of us. Lew and I had read the life of Ramana Maharshi, the early twentieth-century Indian saint, who left his home at seventeen years old to live on a sacred mountain in Southern India. Ramana stayed in a cave on Arunachala Mountain, in deep samadhi , content to just be . Some people who lived at the foot of the mountain recognized that the boy, Ramana, was spiritually advanced and took it upon themselves to take care of him. Had they not been there he would surely have starved to death.

Id come to Japan secretly hoping to meet a Japanese Maharshi . I hoped Sodo-san was my man.

When we arrived at the park at 8:30 that morning we were told that the Grass Flute monk wouldnt arrive before 10. I knew by then that Sodo-san didnt live in the woods; that he spent his nights in a boardinghouse and his days in the park. Still I assumed he would be in the park by five or six in the morning. The mythic aspect of my image of this monk started to crumble.

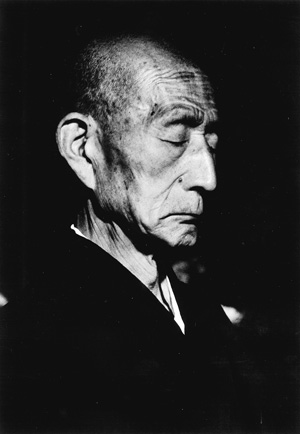

We left the park and went to the nearest grocery store and picked up some fruit and tea as an offering. When we returned a little after 10, he was sitting, legs folded, his bottom resting on his ankles in formal Japanese seiza position, his torso long and upright, giving the false impression that he was a tall man. He wore monks work clothes and a black beret, and his dress and carriage were dignified, suggesting to me a traditional upbringing. He was a thin man with narrow classical features.

Seeing three foreigners standing near him, he picked up a leaf from a bowl of leaves in water, placed it on his lower lip, and holding it in place with two fingers of his right hand played Old Folks at Home. It was the funkiest version of the Stephen Foster tune Id ever heard.

Sodo Yokoyama practicing zazen near Antaiji Temple. Though a shy man by nature, he practiced zazen wherever he was. Here he is in the fields around Antaiji Temple, meditating under the open sky.

2

Noodles and Memories of a Leaf-Blowing Monk

It was a few minutes before noon when Id arrived at the Komoro Train Station and I didnt want to disturb Joko when he was about to have lunch. I knew he would invite me to join him and run around to prepare something more substantial than the meager fare he usually made for himself. Thats the way Japanese are. So, before calling him, I went to a noodle shop on the second floor above a pharmacy across from the station to have some lunch.

The place was small. Five tables and a counter. Though it was noon there were no other customers. I sat at the counter. A small thin woman Id guessed to be in her early fifties, grey streaks in her permed black hair, tied in the back, came to take my order. I assumed she was the owner. The TV was on, an NHK serial drama that Id been watching at my in-laws home in Sakai City, and I immediately became absorbed in it.

What will you have, sir?

I ordered udon noodle soup with tororo (grated yam).

The story on the TV dramatized the life of Hanako Muraoka, the woman who translated Anne of Green Gables into Japanese. She grew up during the Taisho period, just before the fascists takeover of the country. This period from 1911 to 1925 is referred to as the Taisho Democracy, a brief interlude in the history of Japan, when the influence of the democratic ideals of the West seeped into the consciousness of Japanese intellectuals.

Though Hanako Muraoka was born at the end of the Meiji era, her coming of age was during that Taisho period when individual expression was no longer frowned upon by many of the young learned people. If Sodo-san was reading some of the popular writers of this period, since he, too, came of age at this time, he may very well have been influenced by the same democratic spirit of the times.

Your udon , the woman said, as she placed a tray with a bowl of noodles and a small dish of daikon pickles in front of me.

I thanked her, split my chopsticks and started eating while I kept my eyes and ears on the drama of this young, educated Hanako returning to her country village.

Next page