ISSUE 2, FEBRUARY 2018

AUSTRALIAN FOREIGN AFFAIRS

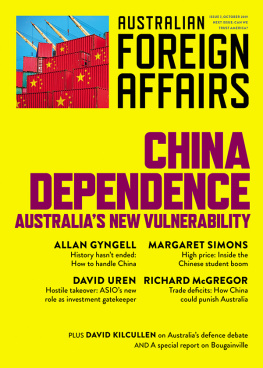

Australian Foreign Affairs is published three times a year by Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd. Publisher: Morry Schwartz. ISBN 978-1-74382-0162 ISSN 2208-5912 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers. Essays, reviews and correspondence retained by the authors. Subscriptions 1 year print & digital auto-renew (3 issues): $49.99 within Australia incl. GST. 1 year print and digital subscription (3 issues): $59.99 within Australia incl. GST. 2 years print & digital (6 issues): $114.99 within Australia incl. GST. 1 year digital only: $29.99. Payment may be made by MasterCard, Visa or Amex, or by cheque made out to Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd. Payment includes postage and handling. To subscribe, fill out and post the subscription card or form inside this issue, or subscribe online: www.australianforeignaffairs.com or subscribe@australianforeignaffairs.com Phone: 1800 077 514 or 61 3 9486 0288. Correspondence should be addressed to: The Editor, Australian Foreign Affairs Level 1, 221 Drummond Street Carlton VIC 3053 Australia Phone: 61 3 9486 0288 / Fax: 61 3 9486 0244 Email: enquiries@australianforeignaffairs.com Editor: Jonathan Pearlman. Associate Editor: Chris Feik. Consulting Editor: Allan Gyngell. Deputy Editors: Kirstie Innes-Will and Julia Carlomagno. Management: Caitlin Yates. Marketing: Elisabeth Young and Georgia Mill. Publicity: Anna Lensky. Design: Peter Long. Production Coordinator: Hanako Smith. Typesetting: Tristan Main. Cover image by T.J. Kirkpatrick / Bloomberg via Getty Images.

Contributors

Cynthia Banham is a visitor at the Australian National University and a University of Queensland research fellow.

Kim Beazley is a former defence minister and former Australian ambassador to the United States.

Andrew Davies is a program director at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

Anna Fifield is the Tokyo bureau chief for the Washington Post.

L. Gordon Flake is the CEO of Perth USAsia Centre.

Jonathan Head is the BBC South-East Asia correspondent.

David Kilcullen is a US-based counterterrorism expert, a former Australian Army officer and a contributing editor at the Australian.

Hamish McDonald is world editor of the Saturday Paper and the author of two books about Indonesia.

Mary-Louise OCallaghan is a former South Pacific correspondent for Fairfax Media and the Australian.

Ian Verrender is the ABCs business editor.

Michael Wesley is dean of the College of Asia and the Pacific at the Australian National University.

Editors Note

TRUMP IN ASIA

D onald Trumps election victory was described by some of his more anguished critics as an American tragedy, but this vastly understates the extent of the problem.

The tragedy and any fallout is global.

Trumps leadership, marred as it is by a mix of inwardness, ignorance, lies, vanity and incoherence, is undermining the credibility, power and prestige of a nation that remains the worlds dominant military, economic and cultural power. Despite the phenomenal rise of China, it is worth recounting the ways in which the United States continues to lead in each of these spheres. Its military spending last year was more than triple that of China (which ranked second); the US dollar remains the worlds chief reserve currency, and Americas gross domestic product was 50 per cent higher than Chinas (which ranked second); and the website, film and television show with the largest global reach in 2017 were, respectively, Google, Star Wars: The Last Jedi and Game of Thrones.

The United States grip on power is weakening, particularly in Asia, but it starts from an extraordinarily high base. Which is to say: Trump not only has much to lose, but also a capacity to cause immeasurable global harm. International agreements on climate change and trade are scrapped or in doubt; tensions in North Korea edge closer to war, possibly nuclear; and everywhere, xenophobes and demagogues are emboldened.

For Australia, this poses two main challenges.

The first is to conduct and develop the relationship with the countrys main ally when it is led by a president whose personality is tempestuous and whose instinct is to mistrust alliances.

The second involves responding to the impact that Trump will have on a fast-changing Asia. China ranks second on most global indices of power but it is catching up, fast. Its economys size, adjusted for price differences, already exceeds that of the United States. Militarily, most analysts believe that, in a war in its neighbourhood, such as over Taiwan, some of its capabilities could match those of the US. There is little sign despite Trumps claim after his twelve-day trip to Asia of a great American comeback.

The power balance in Asia is changing, Trump fuels the instability, and countries are reacting. Australia and Japan are forging closer defence ties, with the prospect of Japanese troops returning to Darwin. The two nations are considering more formal arrangements with India and the US an embrace viewed unhappily by China. Australia and others in the region are re-examining old enmities and considering new alignments, as well as the type of defences they require and the associated cost, as they try to understand their place in this rapidly evolving global order.

Jonathan Pearlman

THE PIVOT TO CHAOS

Australia, Asia and the president without a plan

Michael Wesley

No American president indeed, no modern celebrity has so monopolised our attention as Donald Trump. Rarely is the T-word far from the centre of conversation and consciousness; its a trigger for humour, outrage, despair and mystification. A dollop of the Donald brings effervescence to any discussion. Trump has become the harbinger of so much that alarms us in our contemporary world: populism, political polarisation, crass consumerism, middle-class despair, the decay of respect and moral standards.

Except in Asia. Obsession with Trump is a Western phenomenon. Of course, the forty-fifth American president is discussed in Asian societies, but not with the same intensity as in the West. To travel to Asia is to enter blissfully a Trump-muted zone, free from the saturation coverage of every tweet and micro-detail in the White House soap opera. The American president is spoken about, but in a business-like, unemotional way and then the conversation moves on. Talking about US foreign policy in Jakarta, New Delhi or Manila reminds one of what such discussion was like in our society before Trump was elected.

And yet the impact of Trump will arguably be greater in Asia than in any other region. Asia has relied heavily on American power, rather than on institutions and rules, to provide the stability that has allowed the regions astonishingly rapid development. It is also where a rising China represents the most determined and sustainable challenge to American power. Asian states are not blind to the sudden change of direction in American foreign policy delivered by the Trump administration. They simply view American power differently to us. Understanding this difference will be essential to how Australia adjusts its relations with its region during the Trump era.

Americas triumph

To comprehend the magnitude of Trumps impact on the United States role in Asia, we need to begin with the past quarter-century of bipartisan American strategy in the region. American foreign policy focused on a single objective after the Cold War: to prevent the rise of a rival power similar to the Soviet Union. There were three elements to this strategy.

Next page