ISSUE 7, OCTOBER 2019

AUSTRALIAN FOREIGN AFFAIRS

Australian Foreign Affairs is published three times a year by Schwartz Books Pty Ltd. Publisher: Morry Schwartz. ISBN 978-1-74382-1152 ISSN 2208- 5912 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior consent of the publishers. Essays, reviews and correspondence retained by the authors. Subscriptions 1 year print & digital auto- renew (3 issues): $49.99 within Australia incl. GST. 1 year print and digital subscription (3 issues): $59.99 within Australia incl. GST. 2 year print & digital (6 issues): $114.99 within Australia incl. GST. 1 year digital only auto-renew: $29.99. Payment may be made by MasterCard, Visa or Amex, or by cheque made out to Schwartz Books Pty Ltd. Payment includes postage and handling. To subscribe, fill out the form inside this issue, subscribe online at Editor: Jonathan Pearlman. Associate Editor: Chris Feik. Consulting Editor: Allan Gyngell. Deputy Editor: Julia Carlomagno. AFA Weekly Editor: Dion Kagan. Editorial Intern: Lachlan McIntosh. Management: Elisabeth Young. Marketing: Georgia Mill and Iryna Byelyayeva. Publicity: Anna Lensky. Design: Peter Long. Production Coordination: Marilyn de Castro. Typesetting: Akiko Chan. Cover photograph of containers by narvikk/Getty Images.

Contributors

Ben Bohane is a Vanuatu-based photojournalist, producer and policy analyst.

Melissa Conley Tyler is director of diplomacy at Asialink at the University of Melbourne.

Greg Earl was The Australian Financial Reviews Japan correspondent and a board member of the AustraliaJapan Foundation.

Astrid Edwards hosts The Garret podcast and teaches at RMIT University.

David Fettling is a journalist focusing on South-East Asia and an AFA Next Voices winner.

Allan Gyngell is national president of the Australian Institute of International Affairs and an honorary professor at the Australian National University.

David Kilcullen is professor of international and political studies at the University of New South Wales and a contributing editor at The Australian.

Richard McGregor is a senior fellow for East Asia at the Lowy Institute.

Margaret Simons is a board member of the Public Interest Journalism Initiative and an associate professor at Monash University.

David Uren was economics editor of The Australian and is the author of Takeover and The Kingdom and the Quarry.

Editors Note

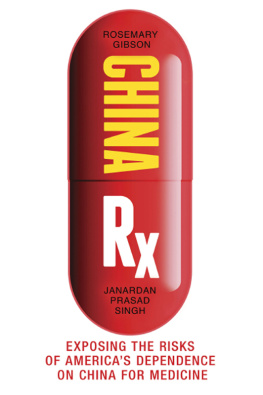

CHINA DEPENDENCE

O n 6 May 2008 Australia declared that China was now its largest trading partner. This development had actually occurred in 2007, but it was only announced by trade minister Simon Crean once annual figures had been released. Still, Crean was reserved: Japan will continue to be Australias largest export destination for the foreseeable future.

A year later, China overtook Japan as Australias largest export market. China now accounts for 40 per cent of Australian exports more than the combined total of the next three countries: Japan, the United States and South Korea. No other developed country is as reliant on trade with China especially not the United States, which has less to lose from a Chinese downturn. This puts Australia in an unusual position. Countries that have been central to Australias economy, such as Britain, the United States and Japan, all share similar geopolitical outlooks. China views Asias power balance differently, and is increasingly capable of reshaping it.

For Australia, this is causing deep anxieties. The worry is that political or diplomatic disagreements with China will prompt it to suddenly disrupt the flow of iron ore, or coal, or students, or tourists. Or that it will misuse its growing presence and assets in Australia. Security and economics are tugging Canberra in different directions, as are its values and its interests.

The first challenge is to understand how China operates, and whether Australia is at risk. In the past two years, relations with Beijing have arguably been worse than at any time since the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. The two countries have disagreed over Australias foreign interference laws, the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, the mass detention of Uyghur Muslims and Chinas arrests of Chinese-Australians. Yet trade has soared. China also has its dependencies, and would suffer if, say, it lost its most reliable iron ore supplier. But Chinas willingness to use its trade clout could change, particularly if ties with Australia deteriorate due to its US partnership.

The second challenge is to adapt to this new predicament. Politicians need to consider how to sensibly handle their differences with Beijing. Businesses need to look at whether investment from China poses security risks, and universities at how their student influx affects their financial risk and the campus experience.

The best hope for the nations stability is that China remains our top trading partner. Australia should do all it can to ensure the mutual benefits from the relationship continue, that the costs and risks are contained, and that any future fallout has been anticipated.

Jonathan Pearlman

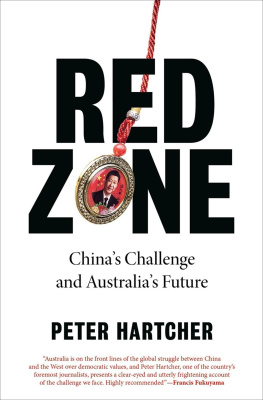

HISTORY HASNT ENDED

How to handle China

Allan Gyngell

In April, Kiron Skinner, until recently head of policy planning in the US State Department and a successor to the legendary George F. Kennan, architect of Americas Cold War strategy of containment, described US relations with China as a fight with a really different civilisation and the first time we will have a great power competitor that is not Caucasian.

Her critics, understandably, piled on. Had she forgotten whose aircraft attacked Pearl Harbor? What did race have to do with great power competition? Didnt the MarxismLeninism of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) emerge from Western roots?

But Skinners comments were a revealing acknowledgement by a senior US policymaker of how Chinas distinctiveness is shaping Western responses to its rise. America has never faced a peer competitor such as this.

In Australia, fears of Asian difference shaped strategic and social policy for much of the twentieth century. The White Australia policy was one of its dismal manifestations. And it was indeed a threat from Asia in 1942 that provided the biggest challenge of the nations history. My professional life began in a world in which anxiety about Chinese communist expansionism dominated foreign policy discussions and Australian diplomats in Asia could not speak to their Mao-suited Chinese counterparts, whose government we did not recognise until 1972.

But for forty years now, since Deng Xiaoping began Chinas economic reforms and advised his country to hide its capability and bide its time, Australia has sailed through magic decades in which, as our leaders regularly intoned, we did not have to choose between our prosperity and our security. John Howard could welcome the US and Chinese presidents to address the Australian parliament on successive days in 2003.

Those days have gone. And for Australia, the sense of strangeness is growing.

We have never had to manage a relationship as important as the one we have with China, with a country so different in its language, culture, history and values. Nor one with an Asian state so confident, and possessing so many dimensions of power. Japan may have been the worlds second-largest economy, but in strategic terms it was a client of the United States.

Even at its current slower pace, Chinas GDP is growing each year by roughly the equivalent of the entire Australian economy. Our governments own projections see it surpassing the United States in total economic size (though not per capita income or comprehensive power) by the end of the next decade.