Contents

Guide

Page-list

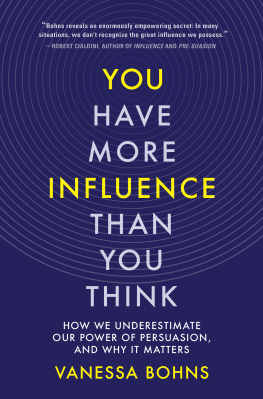

YOU HAVE MORE

INFLUENCE

THAN YOU THINK

How We Underestimate

Our Power of Persuasion,

and Why It Matters

Vanessa Bohns

Copyright 2021 by Vanessa Bohns

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design: Simon Wilkinson Creative

Production manager: Devon Zahn

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Bohns, Vanessa K., author.

Title: You have more influence than you think : how we underestimate our power of persuasion and why it matters / Vanessa Bohns.

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : W. W. Norton & Company, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012207 | ISBN 9781324005711 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781324005728 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Persuasion (Psychology) | Influence (Psychology)

Classification: LCC BF637.P4 B545 2021 | DDC 153.8/52dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012207

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Hanna and Evelyn

Contents

I LOVE TEACHING, but from the lectern at the front of the room it can be hard to tell if youre having any impact at all. You pour your heart and soul into a lesson, only to stare out at a sea of unreadable faces, most of whom will disappear out the door the second class is over. Until one day, you get an email from a former student detailing the influence you had on their life, and, like a bolt of lightning, you experience a moment of teary-eyed recognition of the impact your words and actions can have on others.

Most of us, however, dont regularly get this sort of insight into how we influence others. Whether we affect others in big, life-changing ways (like EMTs or social workers) or in smaller, everyday ways (like good-humored baristas), we typically only gain insight into a very tiny sliver of our true impact. In other words, we may get one email for every hundred students weve taught. And because we rarely get insight into our influence over others, we may chronically underestimate it. After all, if hardly anyone tells you how good your compliment made them feel, or that they were smiling all day about that joke you told them, how would you know you had any impact at all?

Curious about this phenomenon, fellow psychologist Erica Boothby and I thought up an experiment: What if we asked people before they engaged in an ordinary interaction with another person what they expected their impact on the other person to be, and then immediately asked the other person how much they were actually impacted? Would people underestimate the influence they have on others in these sorts of commonplace, everyday interactions?

We recruited people to participate in our study and told them that it essentially consisted of a single task: They were to leave the lab and go outside, approach a random stranger (of the same gender), and compliment them. We even told them what to compliment the stranger on: They were simply to say, Hey, I like your shirt.

Before they left the lab, we asked our participants to guess how good this compliment would make the other person feel. Then we gave them an envelope to hand to the other person right after complimenting them. Inside the envelope was a survey asking the other person how good the compliment made them feel and a second envelope for the approached stranger to put their completed survey in and seal so our participants couldnt see what the other person had said (which could have made strangers less honest in their responses).

What we found in this study has changed the way I interact with strangers: If I have something nice to say to someone, I make the effort to say it. Because I now know my seemingly trivial, awkwardly phrased compliment will make the other person feel significantly happier than I think it will. The strangers participants approached and complimented in our study said they enjoyed the interaction and that the compliment made them feel more flattered and good than our participants expected it would when they imagined giving it. More than this, when we ran the study again and asked participants how annoyed and bothered people would feel being approached and complimented by a random stranger, participants thought their actions would be perceived as much more annoying and bothersome than the people who were approached reported actually feeling.

And its not simply about complimenting someone on their shirt. We found the same pattern of results when we asked participants to find somethinganythingthey genuinely liked about a random stranger to say to them. Overwhelmingly, the recipients of such praise appreciated it more than the people offering it anticipated.

So, people underestimate how good a simple compliment will make others feel, and overestimate how annoying it is to be stopped by a random stranger who wants to express their admiration. This phenomenon also goes beyond superficial praise. People also underestimate how appreciative and good it makes others feel when we express our gratitude for the bigger impact they have had in our livesand overestimate how awkward it makes others feel.

In a study conducted by social psychologists Amit Kumar and Nicholas Epley, participants wrote gratitude letters to notable people in their lives. Some wrote letters to their parents, others to teachers or coaches, and others to friends. Before sending these letters, participants guessed how good the recipients would feel receiving these letters, as well as how awkward the other person would feel reading them. The researchers then contacted the recipients of the letters and asked them how they actually felt when they read the letters. As in the compliment study, participants underestimated how good it would feeland overestimated how awkward it would feelfor the important people in their lives to receive these letters of gratitude.

In another study, Kumar and Epley asked participants to think about how often they wrote these sorts of gratitude letters to other people who had impacted them: Did participants think they wrote such letters too often? Or, not often enough? Overwhelmingly, people reported feeling as if they did not write such letters often enough. It turns out, we all tend to fall short in conveying our gratitude to the very people who would most appreciate hearing it.

My husband and I are certainly not immune to this tendency. When our oldest daughter was born, she had to spend a few days in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) at Grand River Hospital in Kitchener, Ontario. She was fine, but it was harrowing for my husband and me to see our tiny baby hooked up to monitors and IVs. The nurses there were incredible. The care they provided not only to our daughter, but also to us, as first-time parents, was astounding. The three intense days we spent in the NICU with them served as an impromptu crash course in parenting. Once our daughter was discharged, people would comment on how comfortable we seemed changing diapers, nursing the baby, and comforting her through her first vaccines. It was the NICU nurses, we would say. They taught us so much about parenting. We told everyone how amazing our experience with these nurses had beeneveryone, that is, except for them.