Contents

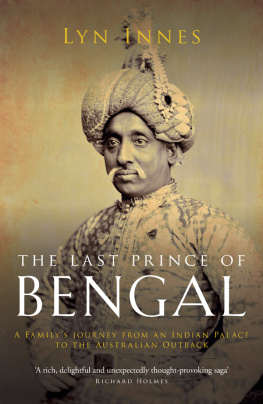

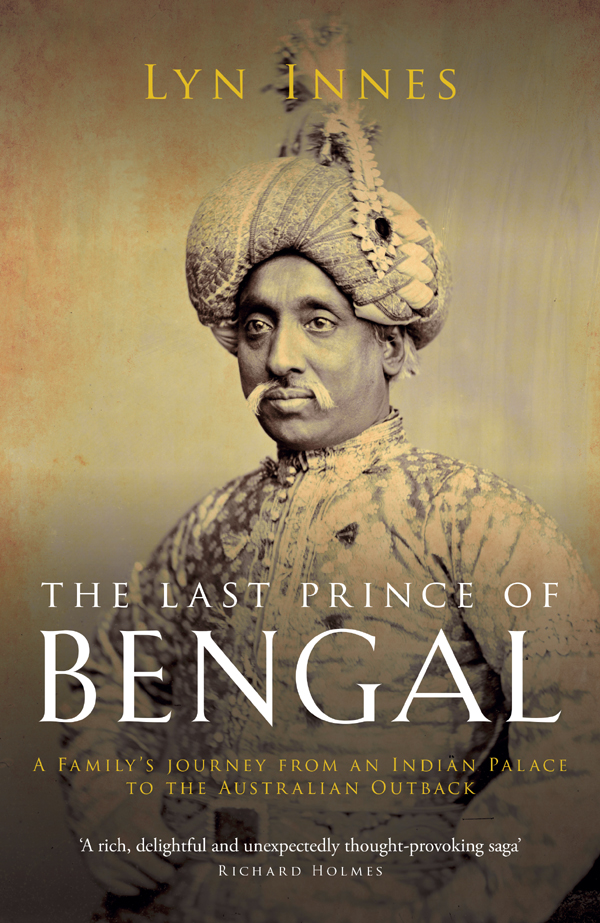

THE LAST PRINCE OF BENGAL

ALSO BY LYN INNES

The Cambridge Introduction to Postcolonial Literatures in English

A History of Black and Asian Writers in Britain, 17002000

Ned Kelly:

Icon of Modern Culture Series

Woman and Nation in Irish Literature and Society, 18801935

Chinua Achebe

The Devils Own Mirror:

Irish and Africans in Modern Literature

THE LAST PRINCE

OF BENGAL

A Familys Journey from an Indian Palace

to the Australian Outback

Lyn Innes

THE WESTBOURNE PRESS

An Imprint of Saqi Books

26 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RH

www.westbournepress.co.uk

www.saqibooks.com

First published 2021 by The Westbourne Press

Copyright Lyn Innes 2021

Lyn Innes has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this Work.

Maps by Lovell Johns.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All rights reserved.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 908906 46 5

eISBN 978 1 908906 47 2

Printed and bound by CPI Mackays, Chatham, ME5 8TD.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Who Did They Think We Were?

But what is a black person then? And first of all, what colour is he? Jean Genet, Les Ngres

A hot summer day in February 1945, a few weeks after my fifth birthday. We had just moved from the slab hut near the road to our new fibreboard house on the hill, and I was watching my mother unpack. At the bottom of a trunk, wrapped in tissue paper, were several old photographs mounted on card. Looking straight out towards the camera in one were my fathers Scottish parents: my grandmother in a high-necked long-sleeved dress, my grandfather in a tightly buttoned suit. There was another photograph of a man in profile an elegant man with a fine, waxed moustache, prominent nose and broad forehead. In the sepia print he is only slightly darker than my Scottish grandparents.

This, my mother told me, was her father. He was Indian no, not an American Indian but from India and he was the man who had painted one of the two oil landscapes that hung in our freshly decorated living room. His painting is unobtrusive: a small, black-framed pastoral scene depicting a field with dark green trees, six inches by nine inches. The colours are sombre. There is no sunlight. Growing up I had assumed that the field was English since it did not look Australian. Examining the picture more closely now as it sits above the desk in my study in Kent, I see that the frame is not black but brown, that the trees in the foreground are a pine and an oak or chestnut, that there are brown cows in the field, and there is a suggestion of a ruined tower in the distance. The scene could be English or French.

This painting is the only thing my mother inherited from her father or at least the only thing she had kept. He had died four years previously, just before my first birthday. To me then and now this quiet and unmistakably European rural scene evokes a distinctive and intriguing aspect of my grandfathers character: somehow, his Indian identity had to include being a painter of European landscapes. My mother later told me that her parents had lived in the suburb of Saint-Cloud, Paris, for several years; that her father had studied art there; and that his work had been exhibited in Paris. Once, she recalled, her parents had visited the Paris zoo, and on recognising an elephant as one that he had known as a boy in India, her father had called it by name and commanded it to kneel, which it did. She told one other story about my grandfather. When he was young, he and his older brother had caused outrage amongst the Hindu community in their neighbourhood by tying firecrackers to the tail of a cow and setting light to them. Their Muslim father had had to pay a large sum of money in compensation. It was a story my mother repeated several times in later life without, as far as I could tell, any concern for the cow.

Our own cows grazed quietly in the paddocks below the house on our isolated mountain farm, named by my father Rhu-na-Mohr, Gaelic for on the bend of the hill. The nearest neighbours were three miles away, the nearest small town, Rylstone, twenty-one miles. From the windows of our new home we looked out over a wilderness of distant mountain ranges. We were taught at home with the aid of correspondence-school lessons and knew no other children. Since there were six of us, three girls and three boys, we did not miss the company of others. Nor did we experience the need to identify ourselves in social or cultural terms, although we were aware that our father was Scottish, and our mother English, and that this made both of them a little different from our neighbours on Nulla Mountain, at least with regard to the way they spoke. My mothers father and his Indian past existed as a vague footnote in the family story.

Soon after I turned seven my parents bundled us all into our 1928 Dodge car, and we drove the fifty miles of dusty roads for the first of several semi-annual visits to Glen Alice, where my grandmother lived on the property she and her husband had bought in 1926, soon after they had arrived in Australia. It was Easter and we began the visit searching for the small gifts that our grandmother had wrapped in yellow tissue paper and concealed behind the yellow and golden autumn leaves of the grapevines, rose bushes and shrubs which filled her English garden.

Indoors we were overawed by the elegance of the wide, verandahed house, and the sitting room with its polished parquet floors, leaded French windows, shining copper tables and crystal glassware. For these special family visits my grandmother dressed formally in a long, green taffeta dress with a white lace collar, and an amber necklace. In the sitting room I remember leafing delightedly through old copies of Punch magazine, looking for cartoons, and glancing through stacks of old newspapers, mostly the Sunday Times, which contained pictures of huskies and Eskimos. These pictures were illustrations for feature articles written by my grandmother and based on the experiences of an Arctic explorer. On top of a chest rested my grandfathers Quran, which we were told to treat with care indeed, we were told that if one of us dropped the Quran, we would have to pay our weight in gold in compensation. We were not told to whom this payment should be made.

On a later visit my grandmother showed us her late husbands our grandfathers court dress and sword. I remember only that the tunic was made of bright green muslin, and that the long, slightly curved sword had a large green stone decorating its hilt. With it, there was a yellowed newspaper cutting from The Times dated 5 June 1914, that showed a photograph of my grandfather wearing an embroidered coat, the sword, and a cap with a feathered plume. There was a caption under the photograph: The Nawabzada Misrat Ali Mirza [sic] of Murshidabad, who attended court on June 5th. The Prince is the son of his Highness, the late Nawab Nazim of Behar, Bengal, and Orissa, and is the uncle of the present Nawab of Murshidabad.