The Dawn Broke Hot and Somber

The Dawn Broke Hot and Somber

U.S. Race Riots of 1964

Ann V. Collins

Copyright 2019 by Ann V. Collins

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Collins, Ann V., author.

Title: The dawn broke hot and somber : U.S. race riots of 1964 / Ann V. Collins.Other titles: US race riots of 1964 | U.S. race riots of 1964

Description: 1st edition. | Santa Barbara, California : Praeger, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018028639 (print) | LCCN 2018030585 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440837258 (ebook) | ISBN 9781440837241 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Race riotsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. | African AmericansSocial conditions20th century. | United StatesHistory19611969.

Classification: LCC HV6477 (ebook) | LCC HV6477 .C654 2019 (print) | DDC 363.32/3097309046dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018028639

ISBN: 978-1-4408-3724-1 (print)

978-1-4408-3725-8 (ebook)

23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available as an eBook.

Praeger

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

www.abc-clio.com

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

To my parents

Martha Luan Carter Brunson Haynes

B. R. Brunson (December 7, 1924December 17, 1988)

Richard Kent Haynes

Contents

Preface

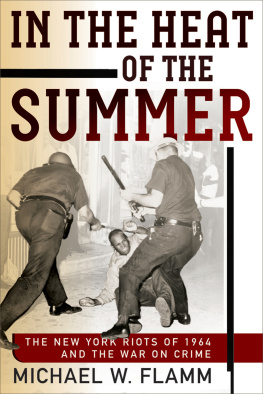

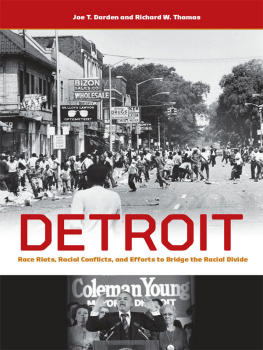

An enraged and exasperated crowd took to the streets of Harlem on the afternoon of July 18, 1964. Residents joined in with activists of the civil rights group Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which originally had organized a protest that day to demonstrate against the disappearance of three civil rights workers in Mississippi almost a month earlier. Instead CORE leaders decided to spotlight the issue of police brutality in light of a recent incident closer to home. Just two days earlier in the Yorkville neighborhood on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, 15-year-old James Powell, an African American summer school student from the Bronx, had been shot and killed by an off-duty police lieutenant who said the boy had charged at him with a knife. The rally culminated in a march to the officers regional precinct, with some of the events leaders pushing for immediate action against him. Satisfied that the encounter between Powell and the officer was being looked into, they left. But the rest of the protesters were fired up and ready to vent their frustrations. What originally started as a peaceful gathering to raise civil rights concerns in the United States soon turned into an avenue for African Americans to voice their dissatisfaction with their status in society. The next morning, front-page newspaper articles blared that thousands of black residents had participated in riotinglooting businesses and taunting their white neighbors. For a total of six nights the violence and destruction continued, first in Harlem, then in neighboring Brooklyn. Soon after, other northern cities erupted with racial violence, too. The dawn broke hot and somber in Harlem yesterday, declared the New York Times on July 20. And, indeed, the dawn of a new era of rioting broke as well.

Before the 1964 Harlem uprising, white Americansfueled by racism and fearwere the primary participants in rioting, using this type of violence on their black neighbors to murder, terrorize, and eliminate whole thriving communities. Their ultimate goal was to deny African Americans an equal footing in society. Dozens, or even hundreds (see During the 1960s and beyond, African Americans rioted hundreds of times to make their voices heard, focusing their ire particularly on the destruction and looting of businesses. James Powells fatal encounter with a police officer in Harlem on that hot July day marked the first of many that would spark unrest throughout the decade and over the years to come. This book focuses on one critical span of timeJuly and August 1964the moment when a new era of activism and race relations in the United States began.

As I pondered in the summer of 2014 what new research to undertake, I became very interested in a time in U.S. history that continues to this day to resonate in the American psyche. That year marked the 50th anniversary of Freedom Summer, the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act, and the epic election between Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwaterall consequential occasions. Having grown up in Central Texas and graduated from Texas State University, Johnsons alma mater, I have long had a fascination with his political career and presidency. I also knew that I wanted to continue the analysis of U.S. riots that I landed on as a graduate student at Washington University in St. Louis. As I dug deeper into the political and social turmoil of the 1960s, I noticed that many studies jumped straight to the Watts riot in Los Angeles in 1965 when they analyzed the racial violence of that decade. But eight major riots, including the one in Harlem, had erupted in four states a year earlier than the one in Watts. In this book, I hope to shed light on those 1964 incidents and fill a gap in the collective violence literature.

More importantly, however, I hope to provide an understanding of why we still seem to be living this history today. Shortly after I finalized the agreement on the idea of this book with my publisher, Praeger, Michael Brown and Darren Wilson had their ill-fated confrontation on Canfield Drive in Ferguson, Missouri, only 30 minutes from where I currently live. Sadly, the scene played out in an all-too-familiar way: a violent encounter between a white police officer and a young African American man, against the backdrop of a city with a predominantly white power structure, a rapid influx of African Americans in a relatively short period of time, a higher unemployment rate among African Americans, a struggling public school system, and systematic institutional racism practiced in daily life. The rioting that broke out in Ferguson looked a lot like what I was researching from the 1960s. In some ways, it was unbelievable that these events were happening five decades after they became so prevalent during the long, hot summers of years ago. In other ways, it is amazing that this type of violence does not occur more often.

Race relations continue to play a significant role in the United States today. Although we have made genuine strides through the blood, sweat, and tears of courageous defenders of equal and civil rights, we still have a long way to go as evidenced in the violence that endures. Valid questions linger about disparities in our criminal justice system, as well as access to good public education, health care, and affordable and decent housing. Debates over policing, civil liberties, free and fair elections, white privilege, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the Confederate flag often pit us against each other rather than unite us to make the United States a more perfect union for all people, not just some. In order to understand these arguments of today, we must recognize the issues of the past in the realm of race relations. It is my hope that

Next page