Race, Riots,

and Roller Coasters

POLITICS AND CULTURE IN MODERN AMERICA

Series Editors: Margot Canaday, Glenda Gilmore,

Michael Kazin, and Thomas J. Sugrue

Volumes in the series narrate and analyze political and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levelslocal, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and popular culture.

Copyright 2012 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wolcott, Victoria W.

Race, riots, and roller coasters : the struggle over segregated recreation in America / Victoria W. Wolcott. 1st ed.

p. cm. (Politics and culture in modern America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4434-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. African AmericansRecreationUnited StatesHistory20th century. 2. African AmericansSegregationUnited StatesHistory 20th century. 3. RecreationSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory 20th century. 4. African AmericansCivil rightsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. I. Title. II. Series. III. Series: Politics and culture in modern America.

E185.86.W65 2012

323.1196073dc23

2012002588

For Erik,

who listens

Introduction

When you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she cant go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children... then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.

Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from Birmingham Jail (1963)

I do not know many Negroes who are eager to be accepted by white people, still less to be loved by them; they, the blacks, simply dont wish to be beaten over the head by the whites every instant of our brief passage on this planet.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (1963)

When Martin Luther King, Jr.s daughter Yolanda Denise asked her father why she could not go to Funtown, she touched on a painful reality that has been largely forgotten. Across the country, North and South, young African Americans discovered that time-honored discriminatory practices limited their access to amusement parks and other recreational facilities. And when they did approach these spaces they often confronted the white violence invoked by James Baldwin. Blacks wanted freedom and mobility without being beaten over the head. They sought to live their lives fully as citizens and consumers without the constraints of segregation. Like King, they wished to protect their children from the reality of racism. Blacks desired not to be loved by whites but to coexist with themand to use the swimming pools, roller-skating rinks, and Funtowns that made urban life in mid-twentieth-century America pleasurable.

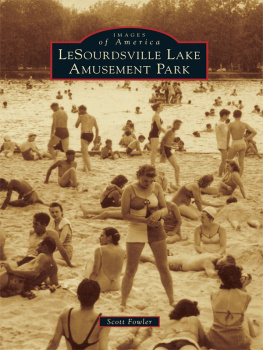

The segregated recreation that the King family encountered in Atlanta was present throughout the country. The problem of segregated amusements was national in scope and the solution required a broad-based movement. African Americans in the twentieth century engaged in just such a movement, not simply for integration but for the occupation of public space in American cities. Among the most coveted urban spaces were those that encouraged young men and women to put aside their daily cares, flirt, and play. This potential for romance, and the association of African Americans with dirt and disorder, led to whites insistence that recreational spaces be racially homogenous. Owners and managers of amusements constantly reassured their white customers that their facilities were clean and safe places to let loose and mix with the opposite sex. The result was an elaborate system of racial segregation in urban recreation. How African Americans challenged this segregation is the subject of this book.

Historians have developed a deep understanding of racial discrimination in housing and labor in mid-twentieth-century cities, yet their understanding of recreation remains shallow. Recreational facilities are public accommodations and can appear marginal compared to economic and political structures.

For historians who focus on political economy, the struggle to open public accommodations is sometimes viewed as legalistic. Focusing on public accommodations can also reify the dichotomy of the innocent North, where Jim Crow supposedly did not exist, versus the evil South, with its system of legal apartheid. Historians of the long civil rights movement reject this dichotomy and demonstrate the culpability of the state in creating and reinforcing patterns of segregation throughout the country. These historians also reject the notion that black power activists commitment to self-defense undermined nonviolence and interracialism, thus leading to the movements decline. Instead, they take seriously the broader goals of black nationalism and refuse to elevate nonviolent activists to near saintly positions in the American imagination.

With these important correctives in mind, is it possible to revisit the struggle to open public accommodations while escaping the integrationist framework? I believe it is, but historians must recognize that our view of what constituted civil rights activism cannot be a zero-sum game. Desegregating public accommodations was a goal powerfully desired by African Americans throughout the country. Just because white liberals, who saw integration as the primary goal of racial equality, also embraced this objective does not diminish its centrality in the black freedom movement. Liberal interracialism coexisted with radical interracialism promoted by nonviolent pacifists and ordinary black citizens who demanded immediate change, not the gradual process of moral persuasion promoted by racial liberals. These movements are related but should not be conflated. Therefore, writing public accommodations out of the civil rights narrative, or downplaying it, is a mistake. Rather, we need to rethink the struggle for public accommodations with the insights of the long civil rights movement historiography in mind.

One way to broaden our understanding of desegregation is by conceiving of it as part of a broader struggle for control of and access to urban space. Popular memories of mid-twentieth-century urban amusements are replete with nostalgia and rarely contain references to segregation. This erasure of white violence has led many to blame the decline of urban recreation on deviant behavior by African Americans in newly desegregated amusements.

The struggle to desegregate public accommodations in the face of white terror did not begin with Rosa Parkss defiant stance in 1954. Even when identifying only activists who employed nonviolent passive resistance to challenge Jim Crow, one has to look at least a decade before the Montgomery bus boycott. The pioneering members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) carried out a major campaign against Chicagos segregated White City Roller Rink in 1942 and fine-tuned organizing strategies that would prove enormously effective a decade later. And prior to the war years many ordinary African American citizens challenged segregated recreation nationwide, swimming at whites-only beaches, boycotting segregated roller rinks, and picketing Jim Crow amusement parks. For most the goal was desegregation, obtaining the right to occupy recreational space, rather than integration, fully sharing facilities with white neighbors. But motivations for engaging in the struggle over recreation varied. Liberal and radical white supporters of desegregation campaignsfor example, the white members of CORE who put their bodies on the line to fight for racial equalitywere more likely to view full integration and interracialism as the goal. Middle-class African Americans often sought the respectability that came with full participation in consumerism. Working-class African Americans frequently conceived of the occupation of public space as a form of community control and a means to protect family members. Together these actors challenged the racial logic that associated white spaces with safety and security.