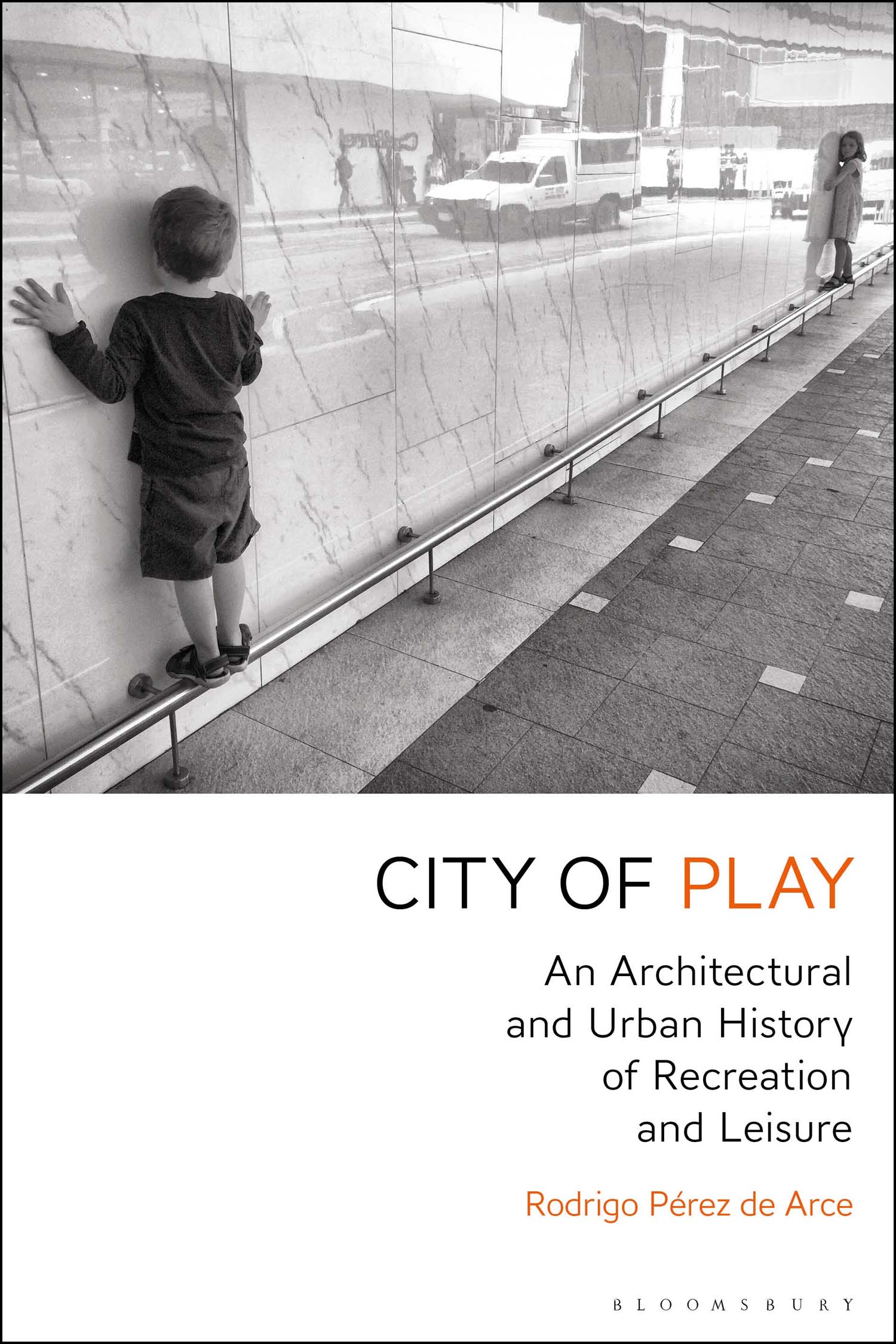

City of Play

To Pilar, Rodrigo and Beatriz

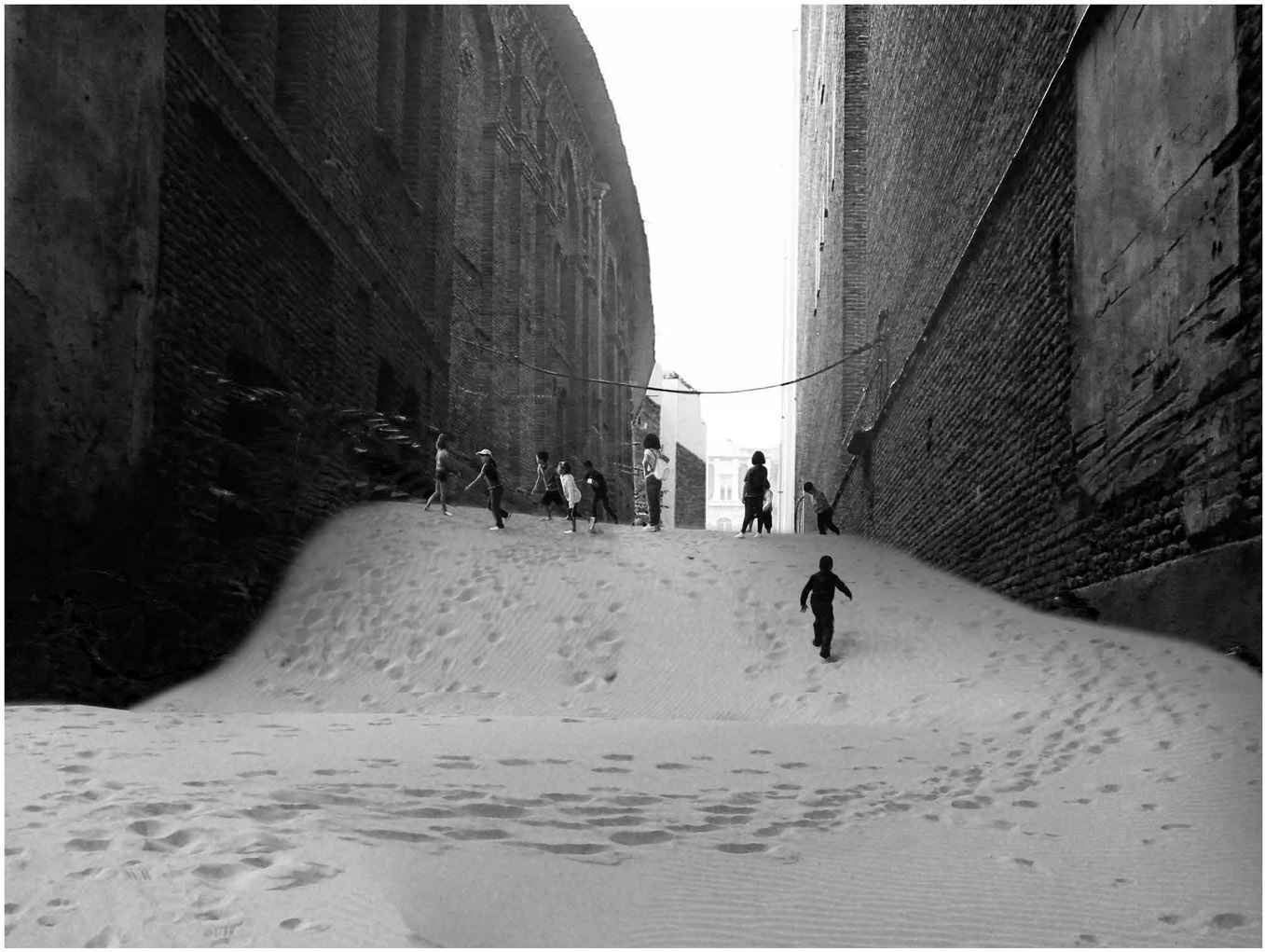

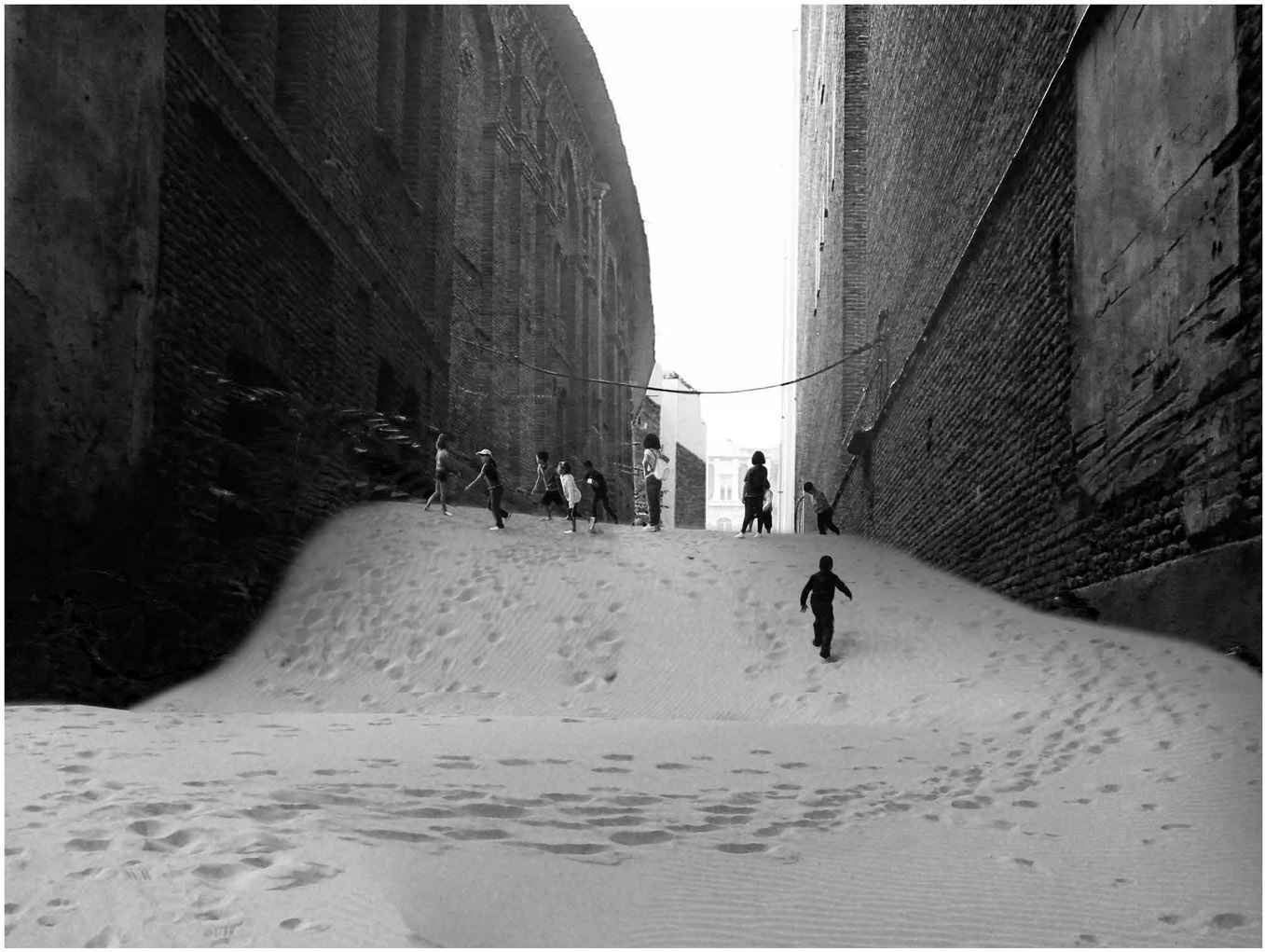

With a massive hauling of sand on the backs of a disused ball court (Beti Jai which translates into always festive) in Madrid, Andres Carretero and Carolina Clocker transformed a derelict space into a playground (2014). See Figure 31(b) for the view of the Basque ball court interior. Image courtesy of Carretero and Clocker; copyright by the authors.

Table of Contents

This research would not have happened if it wasnt for time spent teaching at the Architectural Association, later at Bath and various universities in North and South America. My hosts, the Pringle family, introduced me to English life. Chairman Boyarsky trusted me to teach at the AA, whilst Williams and Winkley supplied me with much needed job opportunities. Through Patrick Hodkinson I got to meet Peter Smithson, as we taught at Bath. The spirit of play was present in diverse ways in the aforementioned settings as it also was in Guillaume Jullian, the late Corbusiers assistant whom I was lucky to befriend. As will become evident, the way ludic inventions interweave with a particular landscape culture in Britain left a lasting impression on me. My long-standing interest in the so-called Valparaiso School resulted in an encounter with Manuel Casanueva who was then forging fascinating links between ludic practice and design inventions. I greatly benefited from seminars held at my alma mater, Universidad Catolica, Santiago, also at Universidad Central Caracas, Cornell, and Harvard GSD. Dean Mostafavi at Cornell, (later at the GSD), and professors Azier Calvo and Jose Rosas in Caracas opened up invaluable teaching opportunities that led to my Doctoral study entitled Materia Ludica. I am also indebted to Jose Rosas for his generous advice. The students and collaborators are too numerous to mention, but my thanks are due to them all.

Teaching assignments at Penn, Porto Alegre, Tucson, Arizona, University of East London and Yokohama, allowed me insights into diverse ludic cultures. Carlos Comas, David Leatherbarrow and Thomas Weaver offered invaluable critical support. My thanks to Professors Frampton and Cohen for their generosity. Also to Emilio De la Cerda, Daniel Taliesnik and Felipe de Ferrari and Ivan Gonzales Viso. Even if they do not know, Alan and Marina Morris helped in great measure and so did Alberto Sato. Paloma Gonzales and Rodrigo Camadros made a decisive contribution with the illustrations. Special thanks to Agustina Labarca for her help in drawing and for her critical insights, whilst Mauricio Pezo, Christian Juica, Eduardo Castillo lent valuable images: my thanks to them all. Finally my thanks to the editors and proof readers.

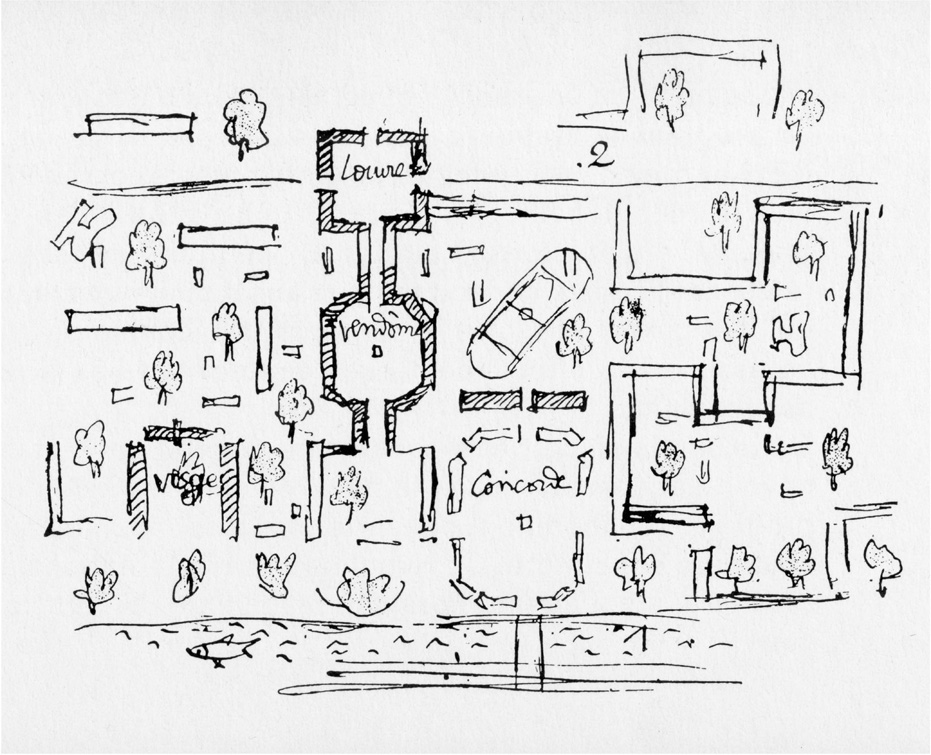

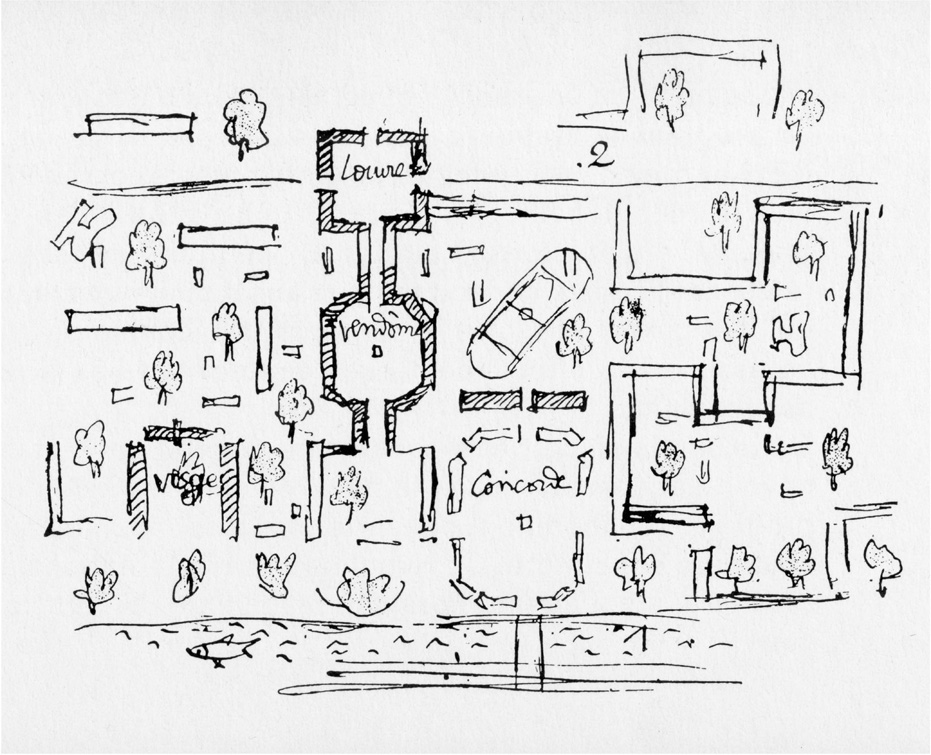

War had been raging all over Europe when Le Corbusier envisioned fusing the contours of Place Vendme, the Court of the Louvre and Place de la Concorde ( a legacy of objects we admire whose dimensions and presence are an unfailing source of joy ) in a linear pattern of slab blocks (Le Corbusier, 1946, 154). His diagram was of course validating the notion of the rednts, their apartment blocks folding about open courts. Where the squares would have formerly hosted sculptures or obelisks, he emplaced a football pitch. By 1953, the Smithsons substituted the CIAM charters four functions (as conceived by Le Corbusier) with forms of association that were lavishly illustrated with vignettes of children at play. Embodied in their Golden Lane scheme, the patterns intimated spontaneity and chance. Later still, and inebriated with the idea of Homo Ludens as the true twentieth-century citizen, Constant Nieuwenhuys (who abhorred Le Corbusiers captive nature), conceived a city of improvisation, chance and play. By 1972, Robert Venturi incited his peers to learn from Las Vegas, the Mecca of gambling where the non-judgmental observer could learn as much as from Rome. The ludic agendas of athletes, children and assorted citizens became prioritized, whilst play was reckoned as significant as programme and concept. Its entry in the twentieth-century architectural agendas was simply unprecedented, and so were the shifting meanings attached to the subject by architects, planners and landscape architects.

Play fills our early years with an intensity that cannot be easily matched. Ushering our minds away from mundane concerns, its praxis and spirit as recreation (to differentiate it from performance (theatrical or musical)) accompanies us through life The child is father to the man said Wordsworth. Genius is childhood recovered at will added Baudelaire. More often than not, modern artists yearned to share the childs enchanted vision: play, we reckon, is by no means solely a childhood affair.

Fascinated with its explorative nature, twentieth-century culture valued its creative and formative potentials. Moreover, it greatly enhanced its visibility through the conception of novel spaces for its deportment. Indoors, the playroom superseded the aristocratic nursery. Outdoors, playing fields sprouted all around. Indeed, play was so highly valued by the fathers of modern urbanism as to endow the modern city with that holiday air that we associate with a superabundance of sunshine and greenery. Play time summoned freedom. An expanded leisure society embraced all. Spare time became a statutory right; Homo Ludens beckoned everyone.

Play has been described as a mirror of ordinary life. Huizinga, Ortega, playground defined?

This enquiry is above all about the play-ground, a particular space released from productive ends in the pursuit of festive plans; about its emplacements, configurations, material description, and equipment. The issue is not so much one of frameworks, scenarios or backdrops, as one of interplays and entanglement with place, space and matter. It involves, therefore, the unveiling of the singular perhaps privileged rapport that binds play as action with architecture as support; it enquires about how these are forged, and about how these may become embedded in ludic practices to such a degree as to render it futile to extricate one from the other. It emphasizes how play manifests itself through artefacts and space.

High altitude field near Uyuni, Bolivia. Image courtesy Christian JuicaC. Juica.

The subject has been extensively explored from such focused perspectives as child play or sport. In surveying the developments on the playground, Ledermann and Traschel delineated fundamental ideas about its structure and spatial requirements only that focused upon children; Hertzberger grounded his ideas about play in evocative architectural descriptions, whilst claiming an uncommon urban primacy to it, yet again his interest was unstructured play. Both Bale and Teyssot looked into sports cultural, political and spatial dimensions, whilst Cranz described the conflictual inscription of playgrounds (for all ages) in the North American park, embracing thus a broader range of ludic expressions, but with a prime concern for the politics. A body of technical manuals offered detailed advice on ludic infrastructures. Recent exhibits at MOMA (The century of childhood), Zurich (The Playground Project), Reina Sofia, Madrid (Playgrounds) made substantial contributions to the subject. All these delineate a fascinating landscape of ideas, events and forms; yet without, on the whole, delving in the urban impact of play.

Next page