Conclusion

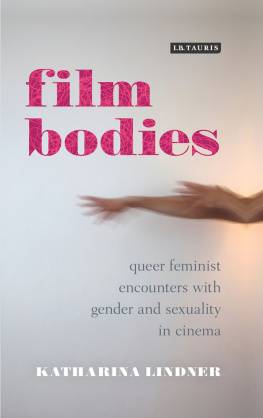

Throughout this book, I have demonstrated how embodied performances have given voice to psychological, biological and cultural layers that map the many aspects of our existence and experiences as lived bodies. I am not suggesting that by giving my subjects a voice I have unmediated direct knowledge of their experiences, but that I have offered a perspectival account of their experiences. Thus, in my dialogue with textual excerpts, theory and my own (felt and embodied) experiences, I have hoped to show how interrogation is possible without an interpretive or directorial stance. This dialogical approach also reflects how I interact with individuals in my DMP and choreographic practice. Consequently, I have re-presented text and film alongside each other and resisted the traditional academic practice of interpretive analysis. By doing so, I locate this work within new developments in the performing arts which form a bridge between academia and professional practice (Allegue et al. 2009; Bannerman et al. 2006). Moreover, in the context of the academy, the notion of producing work for an audience in addition to an academic peer group allows previously discussed intentions to be fulfilled, since the presentation of the work through an artifact allows it to come full circle: from public perceptions through individual processes and mirrored back into the public domain.

In concluding, I would like to revisit the interdisciplinary discourses that I embody and that are interwoven throughout this book in order to consider the emerging implications and contributions of this practice-based evidence, for DMP, dance film, sexuality and gender. In doing so, my intent is to highlight how bodies, intellectual discourse, art, psychotherapeutic and political intervention is one and the same (Alderman 1996).

Embodied discourses in dance movement psychotherapy

I have felt heartened to incorporate writings from established feminist and non (self-consciously) feminist philosophers, scientists, sociolinguists and therapists with a turn to the political. Moreover, a prevailing strength of feminist theory is not its closure of certain positions with which it disagrees, but its openness to its own retranscriptions and rewritings (Grosz 1995: 80). This openness is an essential component of progress and most of these writings have been published during the course of this project and, thus, offer support to my claim that DMP would benefit from theorization of the body and its political implications in practice. In this book, I have suggested further ways of theorizing specific aspects of the therapeutic relationship with an emphasis on, and political awareness of, intersubjective bodies, and body counter/transference. I wonder if this emphasis is distinctly feminist. Perhaps it is, since I not only argue for the importance of how the body is deconstructed but also how it can be re-constituted in relation to sexuality and gender. Thus, it is important to incorporate, within the discipline of DMP, reflexive attitudes towards sexuality and gender as a first step towards changing them.

The DMP profession would benefit from reclaiming its roots in the art form of dance and choreographic practice. As the Embodied Performances show, a doing, undoing and re-doing of sexuality and gender emphasize the bodys experience, psychological and developmental history. In this project, I have taken this a step further by capturing how this process of psychological change is revealed and not only contained in the therapy room. I argue that choreographically forming this process into a dance film for the public allows individuals the possibility of further integration since the therapeutic issues of seeing and being seen are addressed. As I have posited (in ), I approach seeing and being seen directly by using the camera as an intersubjective seer. Below, Vaughan describes the effect of seeing and being seen during Lab 2:

Buddha

Vaughan: it completely took me by surprise I had this image of this Buddha and I cant remember which one it is but is has all these eyes and fingers all over its whole body and this idea of seeing everything and everybody but also all inside and it just got bigger and bigger and it started changing and then suddenly what started happening was almost like seeing the heart and seeing other peoples hearts and when two peoples hearts come together, then they sort of go, phuffff really gentle, cos theres a tenderness there, its not from a place of defence or anything, it did take me completely by surprise, I didnt intend for that to quite happen but it was a different experience of what being observed is about and allowing yourself to be observed.

As a result of the experientials in the Lab, Vaughan describes a process of moving with the image of Buddha and seeing everything and everybody seeing the heart and seeing other peoples hearts. The effect of seeing in this way allowed him to experience tenderness and that this heart connection was not from a place of defence. Woven into this reflection is the reciprocal process of seeing and being seen as well as seeing oneself. Vaughan says: it did take me completely by surpriseit was a different experience of what being observed is about and allowing yourself to be observed. It seems as though Vaughans Buddha embodiment allowed him to re-constitute his notion of allowing himself to be seen, of seeing himself in a more compassionate way.

I have established the politics of seeing (throughout ). For me, therapeutic and social intervention intersect and this is also the basis rethinking psychopathology from a feminist perspective (Brown and Ballou 2002). A feminist approach urges us to reflect on the political implications of everyday life and in our daily practice rather than identifying with a political movement. Therefore, I am not suggesting that everyone become feminist, but I am urging practitioners and artists to consider contemporary feminist principles since they offer ideologically and politically responsible ways of positioning ourselves in praxis where we can work more explicitly with body politics, power and agency. During the Lab, I encouraged each individual to exercise their own sense of agency at various stages. For example, during Lab 2, Vaughan reflected:

If it gets too overwhelming I can just run

Vaughan: at the beginning of the weekend I was thinking about how Beatrice did say that we did have a choice, that we could leave if we wanted to and pull ourselves out, and so there was always this bit in the back of my mind saying, Oh, if it gets too overwhelming, I can just run, but I dont feel that any more and everyones just been really open. Its quite fantastic really its quite rare in our everyday lives.

Encouraging a clients sense of agency in therapy is vital, otherwise the therapist and client may carry unrealistic expectations of themselves and each other into their interactions. The fact that I presented Vaughan (and the group) with the choice to pull out paradoxically acted as a holding mechanism, allowing him to stay.

Within clinical practice, there is the potential to address marginalized aspects of power, sexuality and gender in the clienttherapist relationship, at both a verbal and non-verbal level. In this book, I have demonstrated more explicitly the verbal and non-verbal continuum in DMP as well as stressing the importance of verbal integration. The effects of this are a more integrated understanding of the core themes of sexuality and gender: a physical, emotional and mental awareness. In the following excerpt, Tracey describes her process of integration.

I feel more integrated every time

Tracey: What Im always struck by when I move things is how I feel more integrated every time. It feels like theres been a lot of holding for me, holding of myself and holding of my selves holding others, others holding me and the space felt more held