Contents

The World Turned Inside Out

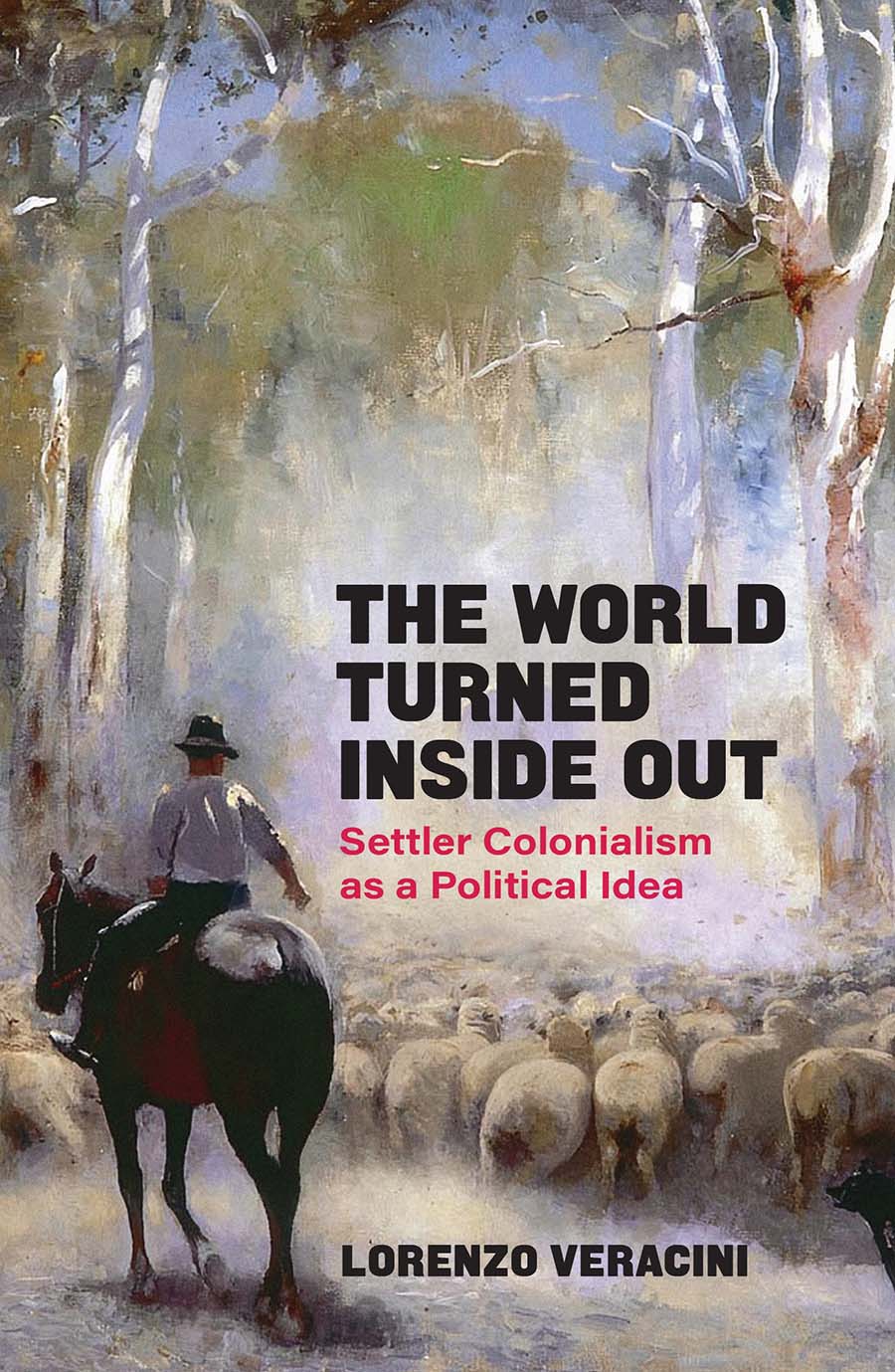

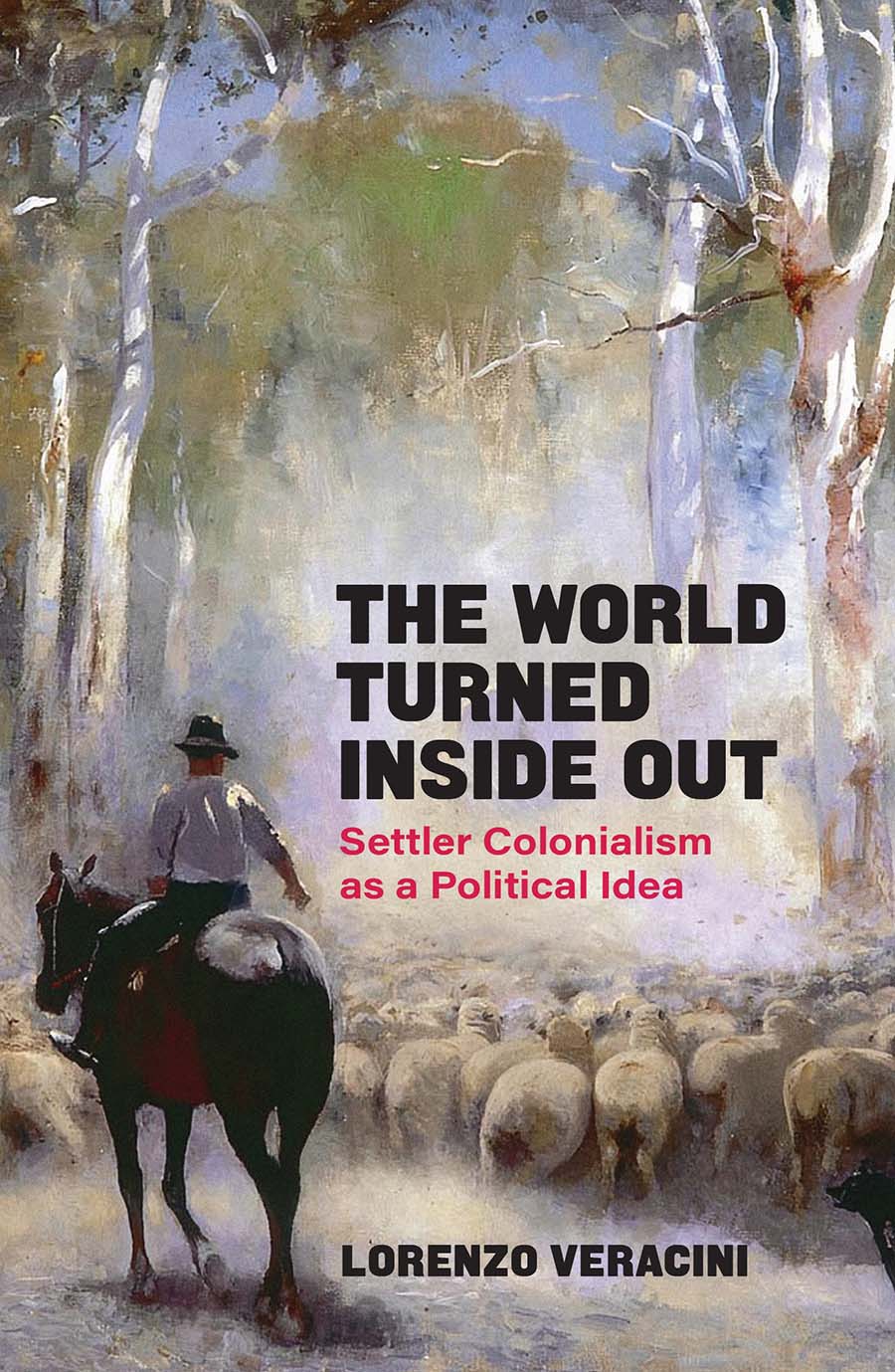

Cover image: Walter Withers, The Drover, Oil on

Canvas (1912). Image above: Thomas Benjamin

Kennington, Homeless, Oil on Canvas (1890).

Both reproduced with permission of the Bendigo Art Gallery, where the two paintings are on display. Together, like panels in a comic book sequence, they tell a story: the child moves away from dysfunction, hunger, and the satanic mills. His sickly pale face turns into a vigorous red neck, rain turns into sunshine, lack of nourishment turns into an enormous amount of meat, and a precarious childhood in the Old World is followed by secure manhood in the new one. This book tells the global history of this fantasy.

The World Turned Inside Out

Settler Colonialism as a Political Idea

Lorenzo Veracini

First published by Verso 2021

Lorenzo Veracini 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-382-3

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-383-3 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-384-1 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Minion by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

This one is for Clare. She was there when I wasnt.

Contents

The World Turned Inside Out

rather than Upside Down

William Lane and his comrades removed to New Australia, Paraguay, after the Queensland shearers strike of 1891 had been ruthlessly repressed. Lane was a well-travelled socialist and a prolific journalist: originally from England, he had been in Montreal and in Michigan before moving to Australia.should be able to withdraw their own share of their societys wealth if they decided to leave. They should be able to travel with an endowment; their wealth should travel with them. The concept was ideal for sovereign people on the move. But the Colonia Nueva Australia was not only about responding to defeat; it was also a way to advocate coherently for political change given the recession, the repression, and the general circumstances of 1890s Australia. If a new world could not be built in one location, it might be built elsewhere (another response to defeat was the establishment of the Australian labour movement; those who decided to persevere aimed to change society where they were). As we will see, Lane is certainly not an isolated example of this sensitivity when facing defeat and crisis. This book appraises the global history of the exchange between emplaced and displaced transformation.

Voluntary displacement can be a political stand, which is ironic, considering that making a stand usually implies a determination to remain still. As this book will relate, settling communities in empty lands somewhere else has often been proposed throughout modernity as a way to head off revolutionary tensions. Building on a growing body of research on settler colonialism as a specific mode of domination and on its political imaginaries, the book uncovers an autonomous, influential and coherent transnational political tradition. It appraises a recurring and yet under-analysed stance: facing the prospect of revolutionary upheaval, many highlighted the need to remove to separate locations while celebrating the regenerative possibilities of such a move. Tradition literally means carrying something forward; it derives from the Latin term for carry across. In the case of the politics of volitional displacement, tradition was both a literal and a metaphorical process. It was by displacement to somewhere else that those who embraced the new locales constituted a political tradition.

Modernity is often linked to the anxious perception of upheaval. Those who decided to relocate as they perceived the impending upheaval that modernity brought contributed to a developing global imagination of settlement. They were opting out of both revolution and reaction and, in a sense, out of modernity or at least what they perceived to be its most intractable contradictions. Their recurring insistence on quiet possession underscores the perception of turbulent times defined by loss, the very opposite of possession. They felt they had to go.

There are many displacements. While volitional and forced displacements are often difficult to disentangle from each other, the two may be considered as opposite ends of a spectrum of possibility. This book focuses on the volitional end of this spectrum, even if those who advocated voluntary displacement would typically have argued that it was an absolute necessity: that there was ultimately no choice. Thus, the books focus does not deny other dislocations there were many or that nonvoluntary displacements did not interact with voluntary ones. Either way, opting out demanded an elsewhere. The places had always been there and were not empty, many indigenous sovereign polities populated these lands, but settler colonialism as a globally expanding mode of domination and new modes of transport provided control and access to many elsewheres.

If you decide to go, it must sound like a viable proposition. You must think you will be empowered in the colony. In the last twenty years or so, settler colonial studies has emerged as an autonomous scholarly Political history remains a nationally framed discipline.

This is problematic because the political projects that advocated displacement escape nationality by definition. They disappear from the frame as they depart, and when they reappear in distant locations they are seen as contributing to the history of the new setting. The political geometry that underpins their politics, the ways in which relocating is politics, is overlooked.

Arneil focused on the Dutch founder of early-nineteenth-century domestic colonialism, Johannes Van den Bosch, who saw the farm colonies he was establishing, the Colonies of Benevolence, as supporting an emerging capitalist regime because productive labourers ready to enter the labour market would be moulded in these secluded spaces (a worthwhile investment, even though the colonies would detract from labour markets in the short term). The colonies became a veritable template in an international network of domestic colonial activity an activity prompted by pan-European social and economic crisis following the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Revolution and colonialism were linked. Indeed, poverty concerned Van den Bosch greatly, but he was more concerned by the possible outcomes of poverty in terms of social instability, against a background of economic depression, rapid industrialisation and urbanisation. His Discourse on the opportunity, the best way of introduction and the important benefits of a General Institution for the Poor in the Kingdom of the Netherlands (1818) argued that, since

the poverty of our times is a consequence of our present social institutions, and must therefore be considered susceptible to a considerable increase, as the most recent circumstances of England, and part of Germany and Switzerland, seem to prove then it is undeniably also true that this must finally have consequences, dangerous as much for the security of society in general, as for the special interest of the more affluent classes; and that the State, by extension, could be subjected to disturbances by others, the more harrowing as the number of its needy members would have grown, and the tendency, the urge, to provide themselves by force with what they have been denied by the course of circumstances, would find stronger encouragement in the greatness of their misery.