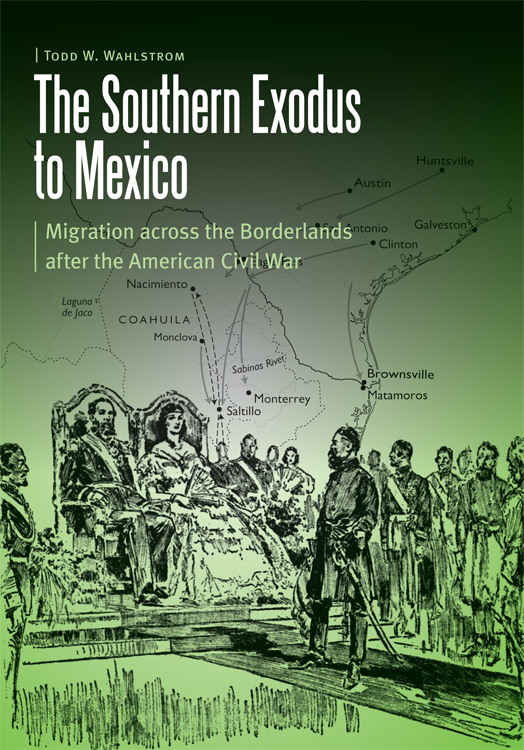

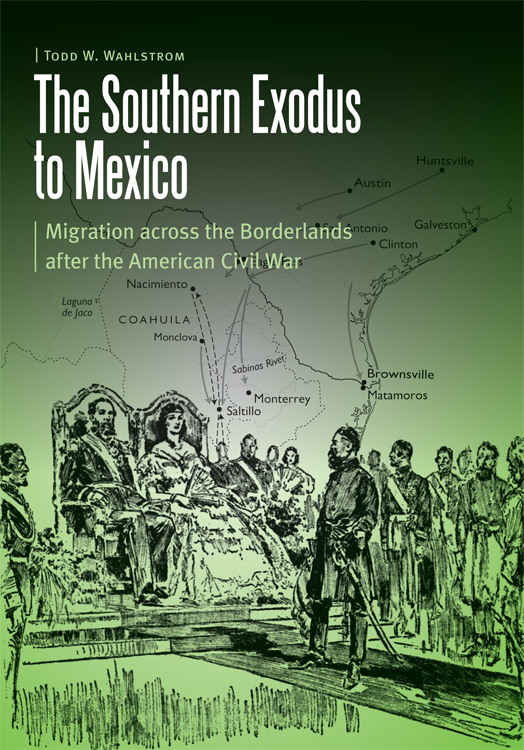

The Southern Exodus to Mexico is an intervention in borderlands history, in black-white-Indian history, in migration history, in economic history, and in the history of national, class, and racial identities. It is also that rare and wonderful kind of historical writing: a tale of roads not taken, of dreams not quite fulfilled. Even though most of the migrants did not achieve all that they had hoped, there is much for us to learn from their ventures. Wahlstrom showsus a dynamic borderland and the peoples who traversed it.

Paul Spickard, author of Almost All Aliens: Immigration, Race, and Colonialism in American History and Identity

The Southern Exodus to Mexico

Borderlands and Transcultural Studies

Series Editors:

Pekka Hmlinen

Paul Spickard

The Southern Exodus to Mexico

Migration across the Borderlands after the American Civil War

Todd W. Wahlstrom

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln & London

2015 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.

Author photo by Matt Yamaguchi.

A portion of chapter 1 originally appeared as A Vision for Colonization: The Southern Migration Movement to Mexico after the U.S. Civil War, Southern Historian 30 (Spring 2009): 5066.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wahlstrom, Todd W.

The southern exodus to Mexico: migration across the borderlands after the American Civil War / Todd W Wahlstrom.

pages cm.(Borderlands and transcultural studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-4634-8 (hardback: alkaline paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-7422-8 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-7423-5 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-7424-2 (pdf)

1. AmericansMexicoHistory19th century. 2. American Confederate voluntary exilesMexicoHistory19th century. 3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Refugees. 4. Southern StatesEmigration and immigrationHistory19th century. 5. WhitesSouthern StatesAttitudesHistory19th century. 6. Coahuila (Mexico: State)History19th century. I. Title.

F 1266. W 34 2015

972'.07dc23

2014036545

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

For Meghan, Liam, and Owen

Contents

Figures

Tables

Map

I would like to express my gratitude to Matthew Bokovoy, senior acquisitions editor at the University of Nebraska Press, for his help with reshaping and finalizing my manuscript for publication. I would also like to thank Heather Stauffer, Joeth Zucco, and Joy Margheim for all their help with completing this book project. I extend much appreciation to Adam Arenson and an anonymous reviewer for reviewing several drafts of my manuscript and for providing critical insights into how to develop my arguments and analysis. Likewise, series editors Pekka Hmlinen and Paul Spickard have been instrumental in guiding the project to its completion and making the manuscript worthy of publication. John Majewski, my former advisor, and Sarah Cline, both at the University of California, Santa Barbara, have also been very supportive and vital contributors to this book.

I would like to thank the personnel at the archival institutions that I have visited while working on this project, especially Reader Services at the Huntington Library, Miguel ngel Muoz Borrego and Lucas Martnez Snchez at the Archivo General del Estado de Coahuila, and the Virginia Historical Society. While working at these research institutions and others, I was able to examine fascinating historical materials and enjoy very productive periods of research and writing. I am likewise thankful for the fellowship and grant support I received while doing the bulk of my research, including a History Department Dissertation Fellowship from the University of California, Santa Barbara, a UC MEXUS (University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States) Dissertation Research Grant, a Mellon Match Fellowship from the Huntington Library, and a Mellon Research Fellowship from the Virginia Historical Society.

I was fortunate enough to present portions of my research at several conferences. The Richards Center Conference The Civil War in Global Perspective at Penn State University and the MESEA (Society for Multi-Ethnic Studies: Europe and Americas) Conference Migration Matters at Leiden University were especially valuable to developing the project. I also published an earlier version of chapter 1 as an article in Southern Historian and coauthored an article on Matthew Fontaine Maury for the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography that helped advance my analysis of southern migration to Mexico after the Civil War.

I extend my largest debt of gratitude to my wife, Meghan, for her unfaltering love and support over these years. My two sons, Liam and Owen (age five and two), have likewise provided support, or more accurately, inspiration for completing this book and brought immeasurable happiness to our lives. My mother, Barbara, brother, Erik, father, Paul, and grandmother, Laura, have also been great sources of support and encouragement. To my family, I extend my greatest appreciation.

Isham G. Harris left for Mexico with a price on his head. As the former Confederate governor of Tennessee, Harris fled the country after the American Civil War. In mid-June 1865, with my baggage, cooking utensils and provisions on a pack mule, he wrote, I set out for San Antonio, where I expected to overtake a large number of Confederate, civil and military officers, en route to Mexico. He was too late. Having missed that group of Confederate migrants, he decided to head for Eagle Pass, Texas, which he reached on the evening of the 30th, and immediately crossed over to the Mexican town of Piedras Negras. The next morning he set out for Monterrey, Mexico, the meeting ground for Confederate exiles crossing the border away from Reconstruction.

Harris was among the vanguard of white southerners who migrated to Mexico after the Civil War, one of the elite Confederates who composed the leadership of the southern migration movement and helped establish the first Confederate colony in Mexico. These Confederate officers were vital to defining southern colonization in the postCivil War era. Indeed, the planning largely sprang from another top-ranking ConfederateMatthew Fontaine Maury, a renowned scientist and Confederate naval officer who came to the helm of this initiative. For Maury, Mexico represented an enticing opportunity for white southerners in the postCivil War world. His fellow white countrymen could escape from U.S. Republican rule and make a fresh economic start by taking advantage of Mexicos agricultural resources. These migrants were expected to contribute their farming skills and a labor forceespecially their former slavesto stimulate the Mexican economy through commercial agriculture. In return, they would secure a prosperous postemancipation life after their lifestyle predicated on slavery had vanished.

Important as these Confederate leaders were to southern colonization, they were ultimately not the backbone of the southern exodus to Mexico. Instead, they were soon eclipsed by a swell of enterprising white southerners of lesser socioeconomic standing. As Harris described, Mexico presents the finest field that I have ever seen. Common white southern migrants (in economic and social terms) came to define southern colonization along lines that both supported the social and political outlook of the leadership and moved it in new directions.

While undertones of racial supremacy helped impel common white southern migrants across the border, the bulk of them were attracted more by the geographic and economic promise of Mexico. That is, more-average white migrants may have harbored a white supremacist perspective that coincided with the attitudes of the leaders of colonization, but they were not as driven by the fear of persecution and Black Republican rule. In seeking out Mexico, most migrants prioritized the transborder economic possibilities of the postwar era, even while sharing in the racialized prism that was central to the American South, and the United States, during the nineteenth century. They represent a key layer in redefining the dimensions of southern migration to Mexico after the Civil War, shifting away from an existing interpretation that views southern colonization only as an attempt to resurrect antebellum plantations on Mexican soil.

Next page