Contents

Page List

Guide

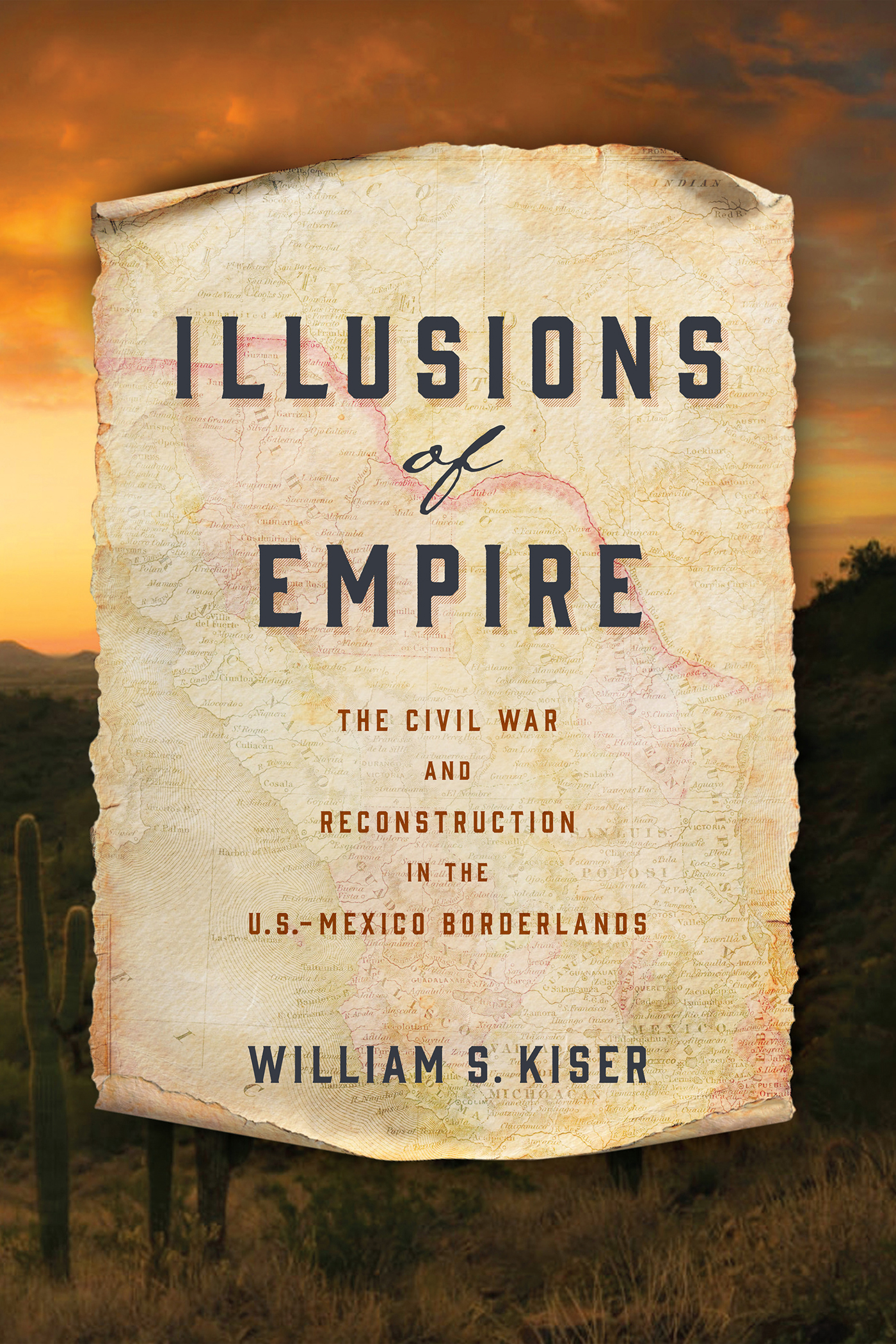

Illusions of Empire

AMERICA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Series editors

Brian DeLay

Steven Hahn

Amy Dru Stanley

America in the Nineteenth Century proposes a rigorous rethinking of this most formative period in U.S. history. Books in the series will be wide-ranging and eclectic, with an interest in politics at all levels, culture and capitalism, race and slavery, law, gender, and the environment, and regional and transnational history. The series aims to expand the scope of nineteenth-century historiography by bringing classic questions into dialogue with innovative perspectives, approaches, and methodologies.

Illusions of Empire

The Civil War and Reconstruction in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands

William S. Kiser

Copyright 2022 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for

purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book

may be reproduced in any form by any means without

written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A catalogue record for this book is available

from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8122-5351-1

For my daughters, Cassidy and Allyson

CONTENTS

Introduction

Just one week before the Confederate siege on Fort Sumter, President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward dispatched Thomas Corwin to Mexico City on a diplomatic mission. Lacking reliable information on the state of affairs in Mexicowhich was just emerging from its War of the ReformLincoln and Seward may have equivocated on some policy details, but they agreed on the overall importance of Corwins ambassadorial assignment.

Eight hundred miles away from Lincolns White House, in the first Confederate capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Jefferson Davis and Robert Toombs were also contemplating foreign relations.

Although their missions were not directly connected, Corwin and Pickett both arrived in Mexico at the dawn of the Civil War, and their activities below the border assumed great significance for the Union and the Confederacy. Aside from the timing and purpose of the trips, one remarkable commonality between Corwin and Pickett was that their respective assignments constituted the most normal diplomatic approaches to Mexico that either side would pursue during the Civil War. Outside of these two menboth of whom traveled in official State Department capacities to meet with Mexican dignitaries in pursuit of formal international arrangementsthe methods that Union and Confederate operatives employed when dealing with Mexico perpetuated a kaleidoscopic array of personal scheming that originated in the antebellum decades. Nowhere would the gravity of this convoluted outreach be felt more acutely than in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, where Union agents, Confederate officers, Mexican governors, French imperialists, independent Indians, foreign filibusters, Hispanic and Tejano revolutionaries, and roving bandits competed for power on the extreme peripheries of national control. As they pursued their own ambitions, these groups promulgated some of the most idiosyncratic modes of diplomacy and intrigue that North America had yet seen, and their ability to do so stemmed from two factors: the eruption of major wars in the United States and Mexico, and the longstanding sense of regional autonomy along the border.

Situated within the historiographies of nineteenth-century Mexican politics, American foreign policy, U.S.-Mexico borderlands, and the Civil War, Illusions of Empire argues for the centrality of Mexican regionalism in the course of hemispheric empire building, as longstanding divisions between centralists and federalists seeped across the border to influence Union and Confederate strategy in the Civil War as well as Greater Reconstruction initiatives during and after that war. Confederate leadersJefferson Davis and his secretaries of state among themambitiously imagined a stand-alone nation that included a Pacific coastline and portions of Mexico as slave states, and they believed that the backing of regionalist governors in Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Len, and Tamaulipas could not only drive that expansionist agenda but also facilitate the vital export of Southern cotton to Europe and Asia. United States officials, including Lincoln and Seward, correspondingly feared that Mexican support for the South and foreign routes around the U.S. naval blockade might tip the scales of the war and help secessionists make a reality of an empire they previously could only imagine. Furthermore, Emperor Napoleon IIIs so-called Grand Design created the possibility of an alliance between the illegitimate entities of Jefferson Davis and Maximilian I of Mexico that would have expanded the American struggle into a hemispheric conflict. Unionists hoped to prevent French monarchists from creating an empire of their own in Mexico, because they believed that European footholds in the Western Hemisphere posed a direct threat to the security and sovereignty of the United States.

For these reasons, the U.S.-Mexico border became a focus of international strategies in the mid-nineteenth century. To be sure, formal channels of diplomacy were retained through national embassies and local consulates. But this conventional approach usually failed to achieve the desired resultsthe calamitous Trent Affair of 1861 comes to mind, as does Picketts blundering in Mexico City and John Slidells abortive efforts in Parisand national diplomacy often yielded to personal scheming. As Nathan Citino points out, By focusing on official diplomacy, historians of American foreign relations tend to neglect behaviors on the ground and the complexity of inter-group relations carried on beneath the radar of state policy.

Beyond these direct historical arguments, the U.S.-Mexico borderlands provide a case study for the overt and covert nature of diplomacy in regions of contested sovereignty. North American history is replete with complicated borderlands diplomacy involving various degrees of coercion and accommodation. A middle ground in which Great Lakes Indians met French colonizers in an environment of shared authority, temporary alliances between hegemonic indigenous confederations and imperialistic Europeans during conflicts like the French and Indian War, and treaties that Comanche leaders negotiated with Spanish officials in Texas and New Mexico during the late 1700s are just three of many examples. But several things made the mid-nineteenth-century U.S.-Mexico borderlands stand out in the longue dure of North American diplomatic history. One was the sheer number of actors involved: no less than two dozen military officers, a dozen Indian tribes or divisions of tribes, a dozen foreign consulate officials, half a dozen bandit groups, half a dozen filibusters, half a dozen revolutionary factions, half a dozen Mexican governors, half a dozen American governors, two U.S. presidents and their cabinets, a Confederate president and his cabinet, a Mexican president and his cabinet, a Mexican monarch and his court, and a French king and his court. Another was the simultaneous occurrence of major wars in the United States and Mexico that distracted each nations attention away from affairs on its peripheries, making those borderlands, which stretched more than two thousand miles from east to west, a place where all these actors enjoyed some degree of autonomy. The unconventional approaches to foreign relations along the border line demonstrate the complex ways in which independent local actors can influence the course of global affairs and reveal that borderlands, despite their political porosity, economic messiness, and cultural complexity, can simultaneously enable and stifle imperial growth. This offers a critical new way of thinking about Greater Reconstructionor the dramatic nineteenth-century expansion of American capitalist empire and assimilation of minority racial groupsbecause postwar U.S. officials built upon their diplomatic and clandestine achievements in ways that increased federal power in the Southwest and far beyond.