Contents

Guide

Page List

ONE

MIGHTY

AND

IRRESISTIBLE

TIDE

The Epic Struggle Over

American Immigration, 19241965

JIA LYNN YANG

To my parents,

Ed and Mei-Shin,

for making the journey

We are the heirs of all time, and with all nations we divide our inheritance. On this Western Hemisphere all tribes and people are forming into one federated whole; and there is a future which shall see the estranged children of Adam restored as to the old hearthstone in Eden.... The seed is sown, and the harvest must come.

HERMAN MELVILLE,

Redburn (1849)

CONTENTS

ONE MIGHTY AND IRRESISTIBLE TIDE

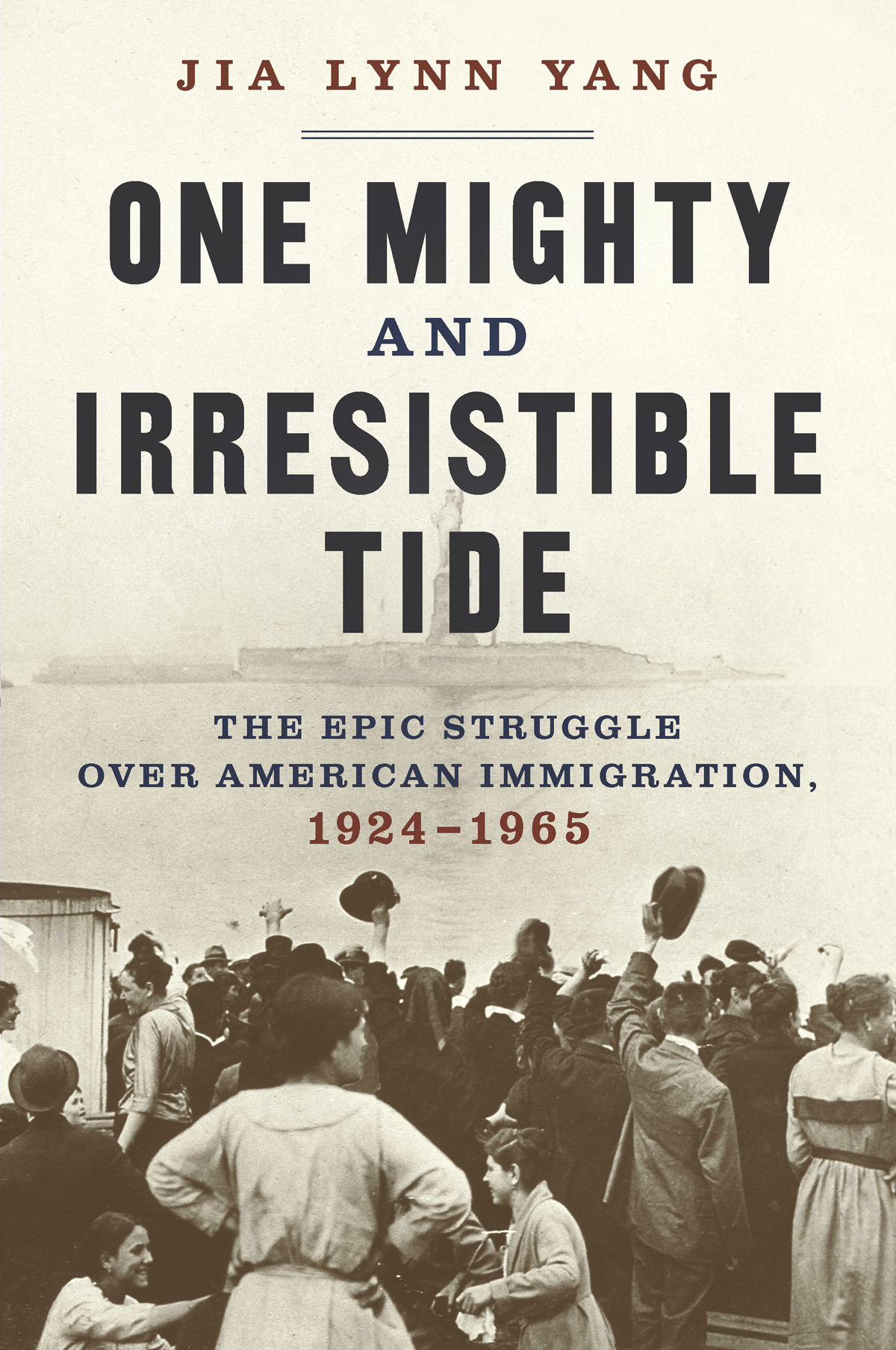

O N NOVEMBER 12, 1954, Edward J. Shaughnessy took one last look around the island that had become his home. A diligent, broad-shouldered man, Shaughnessy had spent decades working his way up the ranks of the countrys federal immigration service, from lowly stenographer to the man in charge of running the famed Ellis Island. So dedicated to the job that he had lived on the island for the last three years, Shaughnessy felt a pang of guilt leaving it all behind and in such a sorry state.

This dollop of land in New York Harbor had once been a mighty gateway to the New World. More than 20 million immigrants had passed through Ellis Island, each embarking on a new life carrying unknown promise, joy, and sorrow. But now the site of their baptism into the American dream was shutting down. At ten-fifteen that morning, officials had processed the last foreigner: Arne Peterssen, a Norwegian seaman who had overstayed his shore leave and had been briefly detained on the island. Next, officials planned to move furniture and equipment to an immigration office on Columbus Avenue in Manhattan. The rest of the twenty-seven-acre complex would be abandoned. Business is closed, Shaughnessy declared.

The news hardly registered with the public. Only the New York Times editorial board paused to eulogize: If all the stories of all the people who stopped briefly or for a longer time on Ellis Island could be written down they would be the human story of perhaps the greatest migration in history.... Perhaps some day a monument to them will go up on Ellis Island. The memory of this episode in our national history should never be allowed to fade.

The idea of the United States as a nation of immigrants is today so pervasive, and seems so foundational, that it can be hard to believe Americans ever thought otherwise. But deep into the twentieth century, the countrys immigrant past had become a hazy memory, widely regarded as a strange blip of history never to be repeated. The year after Ellis Island closed, historian John Higham concluded that the mass immigration that had formed one of the most fundamental social forces in American history had been brought to an end. The old belief in America as a promised land for all who yearn for freedom had lost its operative significance. The Atlantic Monthly, one of the countrys premier publications, did not run a single article about immigration between 1925 and 1953. The issue had fallen so far off the radar that when Senator Herbert Lehman of New York told listeners in a 1952 radio address that he wanted to discuss an important subject with them, he prepared them gently: Some members of this radio audience may be surprised to hear that immigration is an issue. But it is.

The country did not regard immigration as worthy of discussion because, quite simply, there were not many immigrants. A 1924 law passed by Congress had instituted a system of ethnic quotas so stringent that large-scale immigration was choked off for decades. The quotas aimed to limit not only the volume of people entering the country but the type. In order to keep America white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant, the laws sharply curtailed immigration from southern and eastern Europe and outright banned people from nearly all of Asia. More immigrants entered the country in the first decade of the twentieth century than between 1931 and 1971. By the time Ellis Island closed, the share of foreign-born immigrants had dropped into the single digits and kept falling for years as older immigrants passed away. This was exactly as the writers of the 1924 law had intended. As David A. Reed, one of the bills sponsors, crowed just before its passage:

The new immigration legislation marks a complete reversal of our previous policya landmark in our national history. We no longer are to be a haven, a refuge for oppressed the whole world over. We found we could not be, and now we definitely abandon that theory. America will cease to be the melting pot.

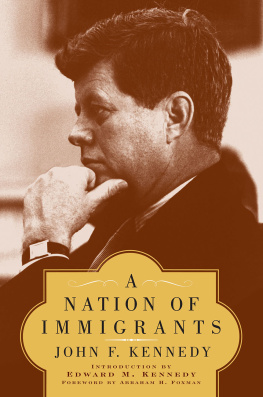

That would have been the end of the story, except that for the next forty years a small number of lawmakers, activists, and presidents worked relentlessly to abolish the 1924 law and its quotas. Their efforts established the new mythology of the United States as a nation of immigrants that is so familiar to all of us now. Through a world war, a global refugee crisis, and a McCarthyist fever that swept the country, these Americans never stopped trying to restore the United States as a country that lived up to its vision as a home for the huddled masses from Emma Lazaruss famous poem. Their effort culminated in 1965, when President Lyndon Johnson signed into law a bill that abolished the quotas and banned discrimination against immigrants based on race or ethnicity. It also decreed that preference be given to immigrants who were reuniting with family members, as well as those with special skills in the arts and sciences.

Not many Americans today know about the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, but it was one of the most transformative laws in our nations history. By ending a system of racial preferences among immigrants, the law reversed a decades-long decline in immigration levels and opened the door to Asian, Latin American, African, and Middle Eastern immigration at a scale never seen beforechanges that are so evident now that they seem to have been inevitable. But while the architects of the 1965 law imagined themselves to be restoring a lapsed ideal, they were in fact doing something unprecedented. For most of this countrys past, it had been firmly established that being an American was inextricably tied to European ancestry. The Immigration and Nationality Act obliterated that notion by daring to outline a vision of belonging that transcended race and ethnic origin, in effect saying to the rest of the world, especially the wide world outside Europe, that all peoples were eligible for the American project.

To the extent that the laws significance has been discussed at all in recent years, it is typically treated as a footnote to the landmark civil rights legislation of the same era, and assumed to have been swept into existence by the undertow of the fight for black equality. While the civil rights movement did popularize a moral framework and contribute political momentum for the law, the Immigration and Nationality Act was the culmination of a distinct, decades-long struggle with its own set of players: the descendants of Jewish, Irish Catholic, and Asian immigrants who saw the countrys immigration system as a painful symbol of nativist prejudice. Some of the key figures remain household names. John F. Kennedy and his brothers Ted and Bobby became champions for immigration reform as they tried to win over white ethnic voters. Others were once-powerful lawmakers whose names have faded from public consciousnessfierce liberals including Emanuel Celler and Herbert Lehman, who were descended from German Jews. Still others were never well known outside a community of immigration activists, including Japanese-Americans whose families suffered in shameful internment camps during World War II. Together this coalition of the powerful and the powerless battled to codify the idea that a person could become wholly American, no matter where she had been born.