Immigrant Experiences

Immigrant Experiences

Why Immigrants Come to the United States and What They Find When They Get Here

Walter A. Ewing

Rowman & Littlefield

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2018 The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Is Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Is Available

ISBN 978-1-5381-0050-9 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-5381-0051-6 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Introduction

Its not easy to leave the country in which you were born and raised. Its home. But sometimes you dont have much of a choice. You may find yourself forced into the position of a refugeefleeing the violence of a military invasion, civil war, gang war, or government persecution. Perhaps conditions arent quite that dire, but you find yourself in a losing battle to stay above the poverty line in a country where most people are poor; so you take your chances in another nation with more plentiful jobs and higher wages than you can find at home. If youre one of the luckier migrants of the world, you live a relatively comfortable life in your home country, but want to pursue bigger and better opportunities in a nation that occupies a more privileged place in the global economy. And whether youre rich or poor, you may simply want to be with family members who have already moved abroad.

Regardless of why people choose to cross international borders, not all intend to say goodbye to their homes forever. Many plan to go back after a few years of working or running a business or going to school abroad, thereby saving the money or acquiring the skills they need to go back home with brighter prospects than when they left. Some follow through with this plan, while some put down roots in their new home and stay for the rest of their lives. And there are those who want to stay in their adopted homeland for good, but are kicked out because they broke a law or violated an immigration regulation. This is often the case for immigrants who are undocumented; that is, those who couldnt find a legal way of migrating to their destination, but who migrated anyway because they felt that there was no viable alternative.

Just as variable as the reasons people leave their home countries are the receptions they receive when they get where they wanted to go. Even within a single destination country, the reactions of native-born citizens to the presence of immigrants can vary widely from region to region, from community to community. Some people give immigrants the benefit of the doubt and actually get to know them, while others automatically view them with hatred and suspicionsentiments that are usually fed by uninformed stereotypes about what it means to be a foreigner. The same group of immigrants might be welcomed in some communities, and met by angry mobs in others.

Regardless of what the native-born population thinks about immigrants, the economies of the nations to which most immigrants travel derive many benefits from their presence. Immigrants represent new workers, ranging from low-tech to high-tech. Immigrants are also new consumers, taxpayers, and entrepreneurs. In communities that find themselves in decline for whatever reason, with native-born residents either dying out or moving out, immigration can be a life-saving transfusion. In the longer term, immigrants literally give birth to new generations of native-born citizensjust as they always haveand a large percentage of natives today are only a few generations removed from their immigrant forebearers. Even so, todays immigrants are not always welcomed by the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of yesterdays immigrants.

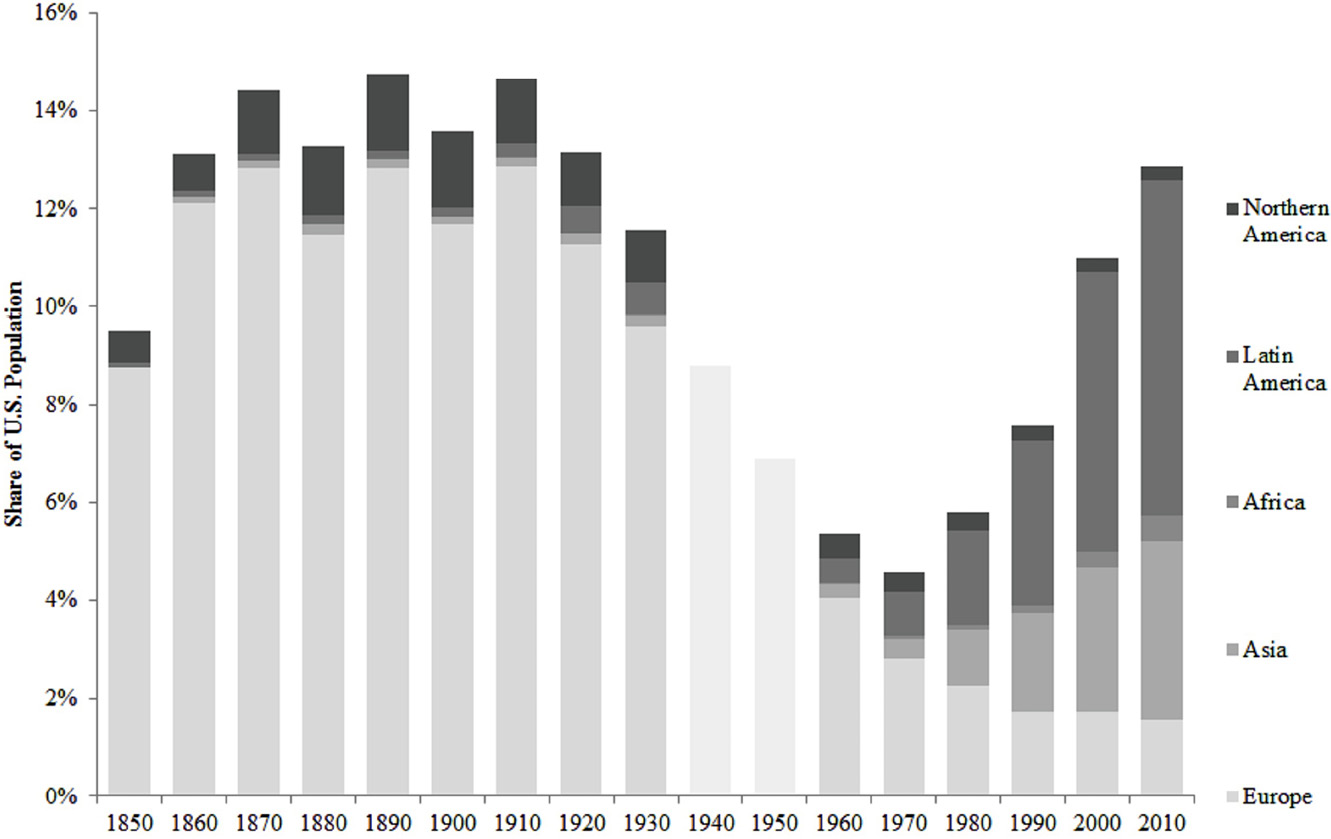

Not all of these themes capture the realities of immigrant life in every country. But they do describe well the lives of immigrants in the United States, both past and present. In the late eighteen hundreds and early nineteen hundreds, immigrants comprised anywhere from 13 percent to 15 percent of the U.S. population and came mainly from Europe. Debates raged over whether or not these immigrants were stealing jobs, committing crimes, and refusing to learn English. Fast forward to today, when the immigrant share of the population again stands at around 13 percent (although immigrants now come predominantly from Latin America and Asia), and the same debates are raging about a new generation of immigrants. Some of the virulent anti-immigrant activists now on the political scene had grandparents who arrived during that last period of large-scale immigrationand who were no doubt reviled by the anti-immigrant activists of that era. It is historical repetition at its worst. It is also socially self-destructive, given that, in addition to the 13 percent of the population that was born somewhere else, another 12 percent were born here, but have at least one immigrant parent. What that means is that fully one-quarter of the U.S. population has a very direct and visceral connection to immigration in some form or another.

Foreign-Born Share of U.S. Population by World Region of Birth, 18502010

Sources: Campbell Gibson & Kay Jung, Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 18502000, U.S. Census Bureau, February 2006; 2010 American Community Survey.

Capturing Complexity

There is no one immigrant experience. There are many experiences of immigration depending on where you start out, where youre heading, and where you finally end up. This book attempts to capture the complexity of these experiences in a systematic, straightforward manner, drawing upon the research of academics, buthopefullywriting in a more accessible style. The book is divided into three parts, and each part contains three chapters. Some material is occasionally repeated in different chapters in order to make each chapter self-contained and easier to read. And each chapter draws heavily from just a few, primarily academic sources from different disciplines that can serve as one-stop shopping for any reader wishing to explore a particular theme in greater detail.

Part 1, The First Steps, describes the forces which motivate migrants to leave their home countries and come to the United States. Chapter 1, Living in Fear, details the refugee experience, with a focus on Jews who fled the anti-Jewish riots in eastern Europe in the 1880s (also known as pogroms), and Iraqi interpreters who fled the horrific aftermath of the U.S. invasion of their country in the early twenty-first century. Chapter 2, Hand to Mouth, changes focus to the migration of people desperately trying to get out or stay out of poverty, detailing the experiences of Irish migrants fleeing the Potato Famine in the middle of the nineteenth century, and the modern-day migration of Mexicans to the United States. Finally, chapter 3, The Ladder of Success, highlights migrants with advanced skills or higher education who are looking for more opportunities for socioeconomic advancement than their home countries provide. For instance, many German immigrants of the 1850s and contemporary migrants from India came here with highly specialized skills in hand, in search of new chances for upward mobility.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.