Copyright 2021 by Curtis Bunn, Michael Cottman, Nick Charles, Patrice Gaines, and Keith Harriston

Cover design by Allison Warner. Cover photo Alessandrobiascioli/Alamy Stock Photo. Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

grandcentralpublishing.com

twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First Edition: October 2021

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bunn, Curtis, author. | Cottman, Michael H., author. | Gaines,

Patrice, author. | Charles, Nick (Journalist), author. | Harriston,

Keith, author.

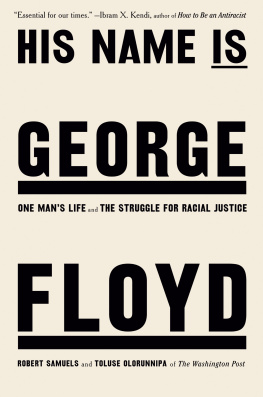

Title: Say their names : how Black lives came to matter in America / Curtis

Bunn, Michael H. Cottman, Patrice Gaines, Nick Charles, and Keith

Harriston.

Description: First edition. | New York : Grand Central Publishing, 2021.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021023045 | ISBN 9781538737828 (hardcover) | ISBN

9781538737842 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African Americans--Social conditions--1975- | Black lives

matter movement. | African Americans--Politics and government. | United

States--Race relations.

Classification: LCC E185.615 .B84 2021 | DDC 323.1196/073--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021023045

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-3782-8 (hardcover), 978-1-5387-3784-2 (ebook)

E3-20210817-DA-PC-ORI

For the courageous Brothers and Sisters who have marched, spoken, rallied, stood up, fought, and died for Black people to matter.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

by Marc H. Morial, President and CEO, National Urban League

I was already Mayor of New Orleans, and Michael Cottman was a seasoned journalist with a Pulitzer Prize under his belt when first we met. But we share a deeper connection as children of the Civil Rights Movement. Born into the waning days of Jim Crow, we are a generation whose childhood was shaped by desegregation and Black Power, who came of age during the cultural backlash of the Reagan Revolution.

In the years since I moved on from mayor to president and CEO of the National Urban League, we have spoken frequently about the issues and developments impacting Black Americans, from the devastation of Hurricane Katrina, through Barack Obamas historic election as the nations first Black president, to the alarming rise of white supremacist ideology under Donald Trump.

There are perhaps no journalists working in the United States better positioned to put the Black Lives Matter movement and the cultural uprising of 2020 into historical perspective than Michael Cottman, Curtis Bunn, Patrice Gaines, Nick Charles, and Keith Harriston. Through moving personal accounts and a detailed grasp of history, they trace the spiritual legacy of anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells to the fearless women who created #BlackLivesMatter and laid the groundwork for a moment when the world is cracked wide open.

I call myself a child of the movement in the most literal of senses: My mother, Sybil Haydel, was home in New Orleans on summer break from her graduate studies at Boston University when she attended a Great Books discussion of W. E. B. Du Boiss Souls of Black Folk. After the book discussion, she became immersed in a conversation with a self-confident young civil rights attorney about Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, which had been decided just weeks earlier. She returned to Massachusetts that August wearing Ernest Dutch Morials fraternity pin.

The struggle for civil rights and social justice and its violent backlash have been an ever-present force in my life from my earliest childhood. I remember my father honking his car horn each evening when he arrived home from work and waiting for my mother to flash the car port lights on and off; this was the system they devised in response to the constant death threats he received as president of the New Orleans chapter of the NAACP. Racially motivated police brutality was among the greatest challenges both during my fathers term as Mayor of New Orleans and during mine. When I took office, New Orleans led the nation in the number of civil rights complaints against its police department.

But 2020 was a year like no other. Even as the COVID-19 pandemic was just beginning to tighten its grip on the nation, the National Urban League identified it as a crisis of racial equity. The limited access to quality health care, lower rates of health insurance, higher rates of chronic illness, and implicit bias in health care delivery that saturated Black America before 2020 were the accelerant that spread the flame of COVID-19 racing through our communities. African Americans and Latinos were more than three times as likely to contract the coronavirus as whites, and African Americans nearly twice as likely to die.

Black workers were overrepresented among low-income jobs that could not be done from home as the economy cratered, and Black unemployment soared by nearly 250% from February to April.

As the nations economic first responders, the National Urban League and our network of ninety affiliates around the nation faced our greatest challenge in a generation. As our affiliates leaped into service as COVID testing facilities, distribution points for food and medical supplies, and emergency employment clearinghouses, we waged a fierce and unrelenting advocacy campaign to target economic relief to communities Black-owned businesses.

Into this simmering cauldron of grief and economic desperationalready overheated by the staggering rollback of civil rights protections under the Trump administrationfell the brutal killing of George Floyd.

For Black Americans battling a disease that left its victims gasping for air, George Floyds final words, I cant breathe, became a heartbreaking emblem of systemic racism. The aloof expression on Officer Derek Chauvins face, as he calmly crushed the life from Floyds body, became an emblem of white indifference to Black suffering.

It was a time to respondnot with despair, but with determination. The National Urban League joined with other civil rights organizations to demand the reforms that became the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act. As a community, we demanded justice for the victims of racially motivated police violence across the country.

This book, like 2020 itself, ends with what Washington Post journalist Dorothy Butler Gilliam calls an explosion of Black hope. But our hope must be tempered with caution. We cannot emerge from this year of crisis only to fall back into the same patterns and practices that created the crisis in the first place. We need to see the span of history encapsulated in these pages and let it inform the future. We must be vigilant, we must be forceful, and we must continue to Say Their Names if we are to sustain the momentum of this movement.