Elizabeth Hinton - America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s

Here you can read online Elizabeth Hinton - America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2021, publisher: Liveright, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s

- Author:

- Publisher:Liveright

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- City:New York

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

If you want to understand the massive antiracist protests of 2020, put down the navel-gazing books about racial healing and read America on Fire. Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination

From one of our top historians, a groundbreaking story of policing and riots that shatters our understanding of the postcivil rights era.What began in spring 2020 as local protests in response to the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police quickly exploded into a massive nationwide movement. Millions of mostly young people defiantly flooded into the nations streets, demanding an end to police brutality and to the broader, systemic repression of Black people and other people of color. To many observers, the protests appeared to be without precedent in their scale and persistence. Yet, as the acclaimed historian Elizabeth Hinton demonstrates in America on Fire, the events of 2020 had clear precursorsand any attempt to understand our current crisis requires a reckoning with the recent past.

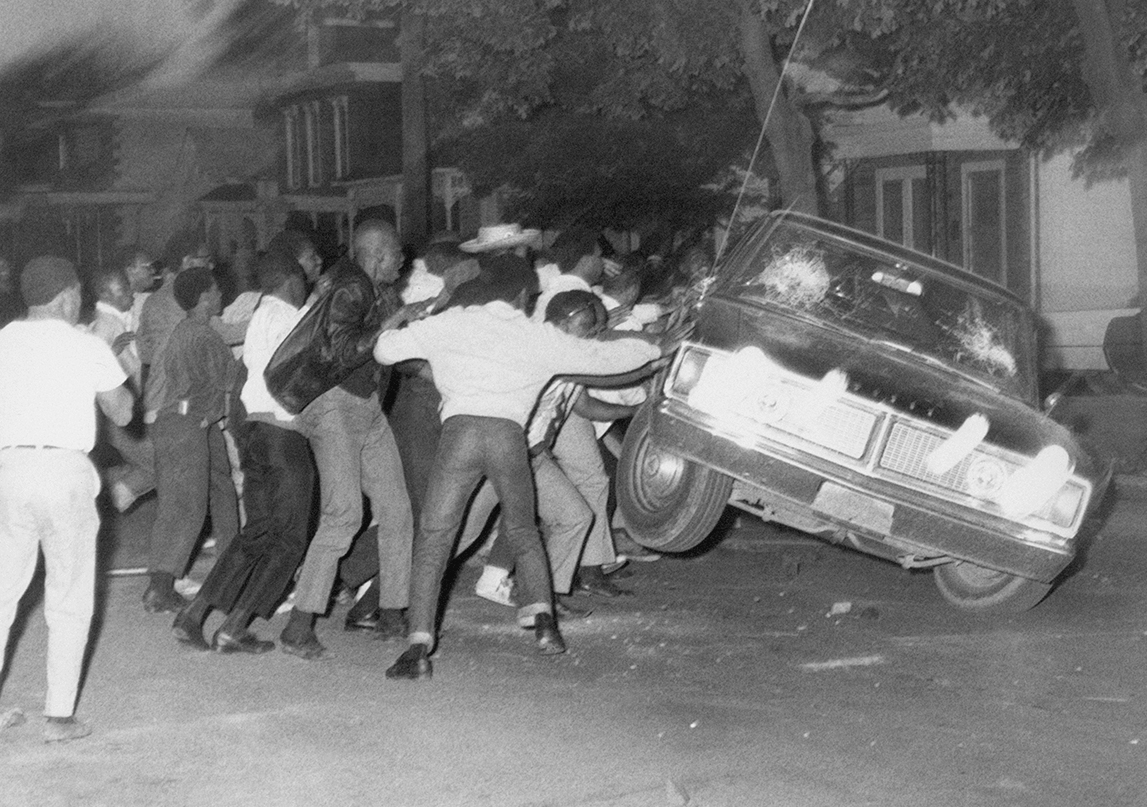

Even in the aftermath of Donald Trump, many Americans consider the decades since the civil rights movement in the mid-1960s as a story of progress toward greater inclusiveness and equality. Hintons sweeping narrative uncovers an altogether different history, taking us on a troubling journey from Detroit in 1967 and Miami in 1980 to Los Angeles in 1992 and beyond to chart the persistence of structural racism and one of its primary consequences, the so-called urban riot. Hinton offers a critical corrective: the word riot was nothing less than a racist trope applied to events that can only be properly understood as rebellionsexplosions of collective resistance to an unequal and violent order. As she suggests, if rebellion and the conditions that precipitated it never disappeared, the optimistic story of a postJim Crow United States no longer holds.

Black rebellion, America on Fire powerfully illustrates, was born in response to poverty and exclusion, but most immediately in reaction to police violence. In 1968, President Lyndon Johnson launched the War on Crime, sending militarized police forces into impoverished Black neighborhoods. Facing increasing surveillance and brutality, residents threw rocks and Molotov cocktails at officers, plundered local businesses, and vandalized exploitative institutions. Hinton draws on exclusive sources to uncover a previously hidden geography of violence in smaller American cities, from York, Pennsylvania, to Cairo, Illinois, to Stockton, California.

The central lesson from these eruptionsthat police violence invariably leads to community violencecontinues to escape policymakers, who respond by further criminalizing entire groups instead of addressing underlying socioeconomic causes. The results are the hugely expanded policing and prison regimes that shape the lives of so many Americans today. Presenting a new framework for understanding our nations enduring strife, America on Fire is also a warning: rebellions will surely continue unless police are no longer called on to manage the consequences of dismal conditions beyond their control, and until an oppressive system is finally remade on the principles of justice and equality.

20 black-and-white imagesElizabeth Hinton: author's other books

Who wrote America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.