2016 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Espinosa Nova by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

Portions of chapter 1 were previously published in somewhat different form in J. Michael Butler, Economic Civil Rights Activism in Pensacola, Florida, in The Economic Civil Rights Movement, edited by Michael Ezra, 91103 (New York: Routledge, 2013); reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis Group, LLC, a division of Informa PLC. Portions of chapter 6 were previously published in somewhat different form in J. Michael Butler, More Negotiation and Less Demonstrations: The NAACP, SCLC, and Racial Conflict in Pensacola, 19701978, Florida Historical Quarterly 86, no. 1 (Summer 2007): 7092; reproduced with permission.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

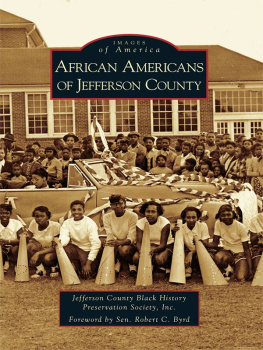

Cover illustration: Young marchers join hands for the 1.4-mile march, Tampa Bay Times/ZUMA (photographer and specific paper unknown, labeled Pensacola Demonstration 75, reference number ycl615)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Butler, J. Michael, author.

Beyond integration: the black freedom struggle in Escambia County, Florida, 19601980 / J. Michael Butler.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2747-2 (pbk: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-2748-9 (ebook)

1. African AmericansCivil rightsFloridaEscambia County.

2. RacismFloridaEscambia CountyHistory. 3. Civil rights movementsFloridaEscambia CountyHistory20th century. 4. Escambia County (Fla.)Race relationsHistory20th century. I. Title.

E 185.93. F 5 B 88 2016 305.896730759990904dc23

2015031949

Acknowledgments

I have long imagined that preparing an acknowledgment of those who helped me in the preparation of this book, a project nearly fifteen years in the making, would either be similar to writing an obituary for the topic or preparing a lengthy acceptance speech for an award that does not exist. For those reasons, and a few more practical ones, I made it the last significant piece that I wrote prior to the works publication. Yet because of the studys relevant nature and the number of people who contributed to the academic insights and conclusions that I ultimately reached, I found that expressing my gratitude was a fitting anddare I say, enjoyableway to cap a transformative intellectual and personal odyssey. The recognition of the numerous debts I have incurred during this manuscripts preparation is, therefore, done in a celebratory fashion with the realization that my study would not be as meaningful or thorough without the help of many people. I also apologize in advance to those who contributed to my research, writing, and thinking about the project that I fail to recognize in this public acknowledgment. Any errors of interpretation, fact, omission, or style within these pages are mine and mine alone.

I have been fortunate enough to work at an institution that has allowed me to complete this endeavor at a reasonable pace, particularly given our teaching load and institutional commitments. The administration and staff at Flagler College have supported me with this book well beyond my 2008 arrival. President William T. Abare twice took a chance on me and, for that, I will always be extremely thankful. Alan Woolfolk, our faculty dean, has been one of my greatest on-campus advocates. He sponsored many research excursions and provided a Fall 2013 sabbatical that allowed me to complete the initial draft. My department chair and fellow historian Wayne Riggs supported numerous funding requests which allowed me to finish the project in an efficient manner. Flagler has also connected me with a number of excellent colleagues in disciplines outside of history, particularly economist Allison Roberts. Allison not only took time away from her position as a new department chair to review my economic and educational figures; she challenged me to go beyond the basic facts I provided and locate statistics that revealed deeper truths about the nature of race relations in Northwest Florida. Without her guidance and tutelage, the final chapter would be much less powerful. Art Vanden Houten answered every political science question I shouted across the hall to his office with patience and clarity, and Hugh Marlowe, Jim Pickett, Doug McFarland, and Tracy Upchurch likewise demonstrated sincere interest in my project from their philosophy, communication, literature, and law perspectives. Terry Bennett satisfied my numerous printing requests in rapid fashion.

One of the benefits of teaching at Flagler College has been the chance to work with a tremendous library staff. Mike Gallen and Brian Nesselrode, the past and current Proctor Library directors, satisfied all of my book order requests and added numerous volumes to our expanding southern history collection. Blake Pridgen scoured the web, seemingly in good cheer, when I needed research aid and offered many interesting insights on the greater civil rights movement. If I ever had trouble with a citationparticularly in Chicago styleKatherine Owens took an almost incomprehensible amount of pleasure in helping me format properly. Finally, Peggy Dyess is the most efficient, friendly, and supportive interlibrary loan librarian I could ever want. I am also grateful to the many students, both past and present, who have expressed an interest in and asked thoughtful questions concerning my project. I remain convinced that they are some of the hardest working undergraduates I have ever encountered. Lyndsey Nauman, in particular, assisted with some mundane steps in the publication process and her husband, Andy Nauman, restructured and formatted the graphs that appear in my appendix.

Several other librarians and archivists also went above and beyond my research queries, such as Kenneth Dukes, Christy Manuel, and Marie LaCap with the Florida Department of Education, Guy Hall from the National Archives at Atlanta, James Mathis and Joe Scanlon from the National Archives in College Park, Carl Chatman and Barbara Rust at the Fort Worth National Archives, George Henderson at the Department of Justices Civil Rights Division, David P. Sobonya with the FBI Records Management Division, and Peter Minarik, at the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Southern Regional Office. Boyd Murphree and Deborah Mekeel assisted during my multiple visits to the State Library of Florida, Sara Logue and Randall Burkett made my experience at Emory Universitys Manuscript, Archives & Rare Book Library quite productive, and Jim Cusick and Michele Wilbanks did the same during my trip to the University of Floridas Special and Area Studies Collections. Allison Burke at ZUMA Press helped with a number of my image permission requests.

I am especially indebted to all of the people from Pensacola and Escambia County who satisfied my numerous questions and requests. It was not always easy to conduct primary source research from nearly 400 miles away, so I relied upon several people to obtain documents that were not at my immediate disposal. Wilma Davio provided invaluable data from the Escambia County Supervisor of Elections, while Ericka Burnett found similar materials as the Pensacola City Clerk. Jackie Dwelle and Teri Szafran supplied materials from the Escambia County School District, and Joel Hollon did a tremendous amount of research to supplement the data I possessed concerning county schools. Likewise, Dean DeBolt recommended I explore specific holdings in the University of West Florida Special Collections and granted permission to use images from the J. Earle Bowden Cartoon Archive in my book. Wendy Zirkin assisted with my Escambia High School yearbook inquiries, while Barbara Hoard and Calvin Avant gave me unprecedented and unlimited access to all of the Escambia-Pensacola Human Relations Commissions existing files. Finally, Ashley Joyner and Scott McDonald answered my records request through the Pensacola Police Department while Darci Cobb and Debbie Coburn provided documents through the Escambia County Sheriffs Office.