Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

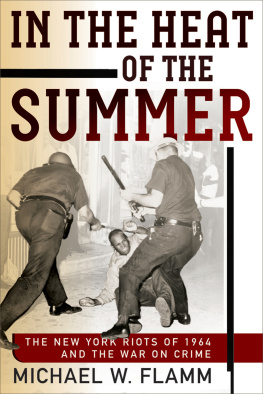

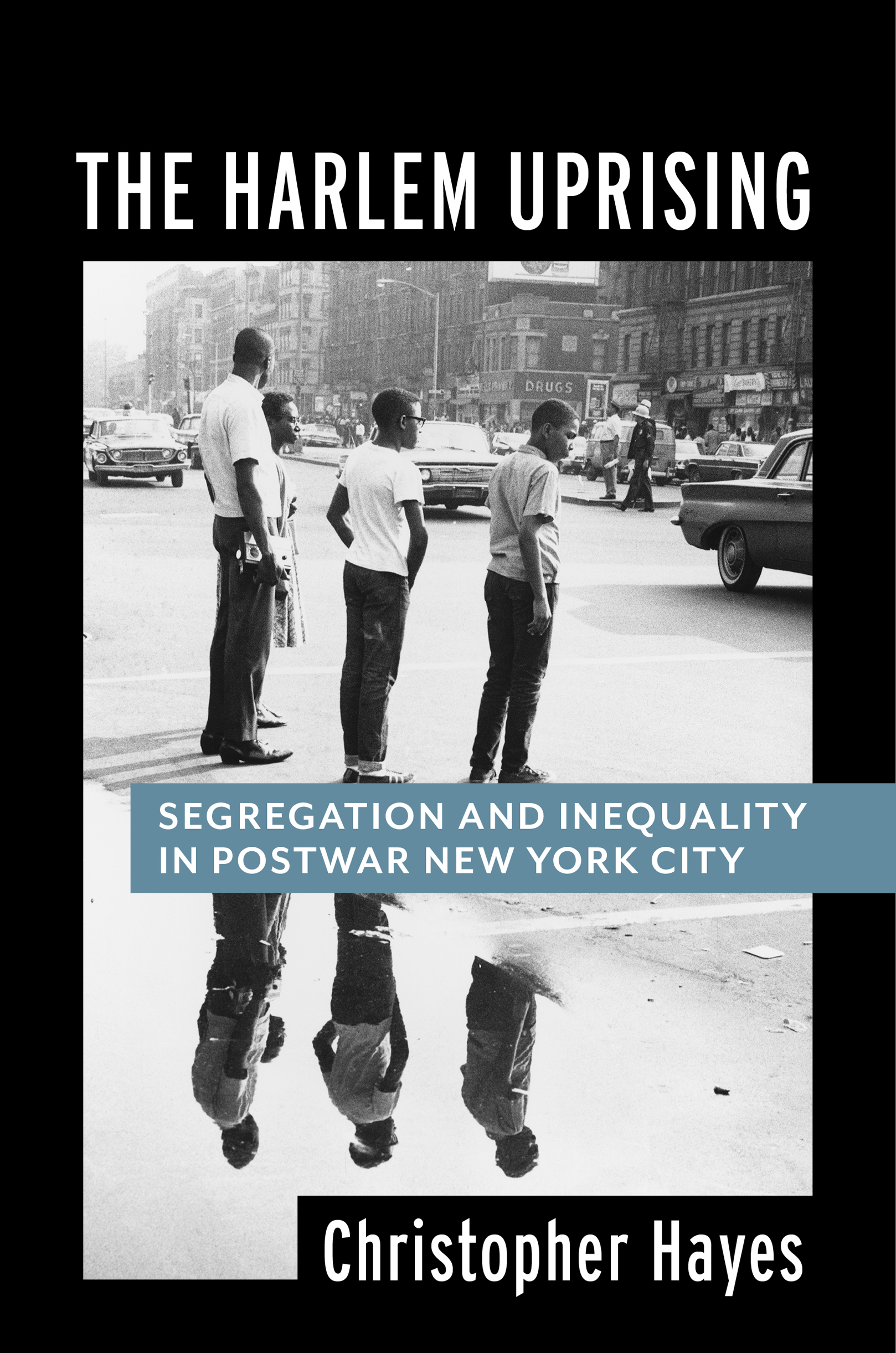

THE HARLEM UPRISING

THE HARLEM UPRISING

Segregation and Inequality in Postwar New York City

Christopher Hayes

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support for this book provided by Publishers Circle member Stephen H. Case.

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2021 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hayes, Christopher, 1979 August 8 author.

Title: The Harlem uprising : segregation and inequality in postwar New York City / Christopher Hayes.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021016648 (print) | LCCN 2021016649 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231181860 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780231181877 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9780231543842 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Harlem Race Riot, New York, N.Y., 1964. | Powell, James, 19491964Death and burial. | African AmericansCivil rightsNew York (State)New York20th century. | African AmericansSocial conditionsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | Civil rights movementsNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | PoliceNew York (State)New York. | Harlem (New York, N.Y.)History20th century. | Race discriminationNew York (State)New York. | New York (N.Y.)Race relations.

Classification: LCC F128.68.H3 H39 2021 (print) | LCC F128.68.H3 (ebook) | DDC 323.1196/07307470904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016648

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021016649

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Neil Libbert / Bridgeman Images

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Contents

Thank you: Mia Bay, without whom there is none of thisno degree, no career, no bookand that is no hyperbole. Beryl Satter, Ann Fabian, and Brian Purnell for their generosity, patience, and forthrightness. They gave quite a bit to someone who was not so sure of what he was doing but thought he knew. I would be nowhere were it not for their efforts. Philip Leventhal, my editor, whose support, guidance, advice, revising skills, and insight have been invaluable and made this book what it is. My outside readers, for their time and constructive criticism. Michael Haskell for shepherding me through the final stages of this project. Rob Fellman and his eagle eye for details. Those at Columbia University Press who worked on my behalf in anonymity. Bob Schwarz. Paula Voos, Lisa Schur, Adrienne Eaton, Will Brucher, Fran Ryan, Dorothy Sue Cobble, Naomi Williams, Mike Merrill, Todd Vachon, Eugene McElroy, Laura Walkoviak, and all at the Rutgers University Department of Labor Studies and Employment Relations. Ronn Pineo. Johanna Schoen and Dawn Ruskai. Everyone who provided feedback on parts of this book at conferences. J. You.

The real danger of Harlem is not in the infrequent explosions of random lawlessness. The frightening horror of Harlem is the chronic day-to-day quiet violence to the human spirit which exists and is accepted as normal.

Dr. Kenneth Clark, Behind the Harlem RiotsTwo Views, 1964

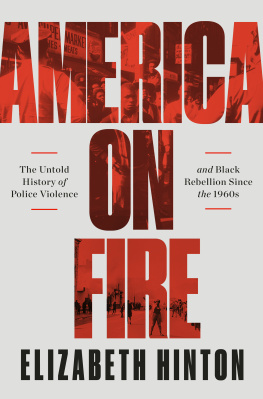

For many African Americans, 1964 was a time of great hope and frustration. The civil rights movement had been winning significant national and regional victories for a decadeBrown v. Board, the Montgomery Bus Boycott, desegregation of public spaces through sit-in campaigns, the Freedom Rides, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 are a fewand the federal government was newly supportive of dismantling the southern apartheid system. These victories all came with challenges, whether states refusing to integrate schools, the lynching of civil rights workers, or terrorists bombing peoples homes and churches, but it seemed like the movement was pushing toward restoring Black Americans constitutional rights, as conferred nearly a century before.

While the millions of Black people living throughout the North applauded these campaigns and what they had won, most of the national victories did not change their lives in significant ways. Black northerners could vote, dine, live, work, and travel as they pleased. Of course, they encountered bigoted individuals who would treat them discourteously or deny them service, but there were no laws mandating the segregation of schools or public accommodations. To the contrary, in the middle of the century, northern cities and states began passing their own antidiscrimination legislation, often well ahead of the federal government. New York City and New York State had some of the earliest and strongest laws against discrimination, beginning with banning discrimination in private employment in 1945. By the late 1950s, there would be laws prohibiting bias in the sale and rental of public and private housing as well. The citys board of education had enthusiastically stated its support for school integration following the Brown decision.

Despite this legislation and lack of blatantly racist statutes, Black New Yorkers suffered enormously under the weight of a vast system of structural discrimination that became more robust and destructive through the fifties and into the sixties, just as the national movement was making substantial strides. Banking and real estate policy compelled them to live segregated, unequal lives in places like Harlem, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Brownsville, and bigoted homeowners and landlords worked diligently to keep out those who had managed to overcome the administrative barriers. The neighborhoods into which the majority of Black New Yorkers were confined were the most overcrowded and contained the oldest housing stock the city had to offer, commonly lacking adequate sanitation and access to quality health care.

The city operated its public schools on the basis of where students lived, resulting in large numbers of segregated institutions, with majority Black schools invariably underfunded, understaffed, overcrowded, and physically decaying. Students tended to learn little of use and fell further behind as they advanced through the grades. Many left high school before graduating, leaving them with no recognized skills in an increasingly education-oriented economy.

Black workers faced a job market offering them low-wage, mostly dead-end service work, with manufacturers leaving the city by the month and white workers wielding an iron grip on construction. The jobs that the city was gaining, in areas like finance, insurance, advertising, and law, required some combination of education, experience, and connections that most Black residents of the city would not have, and for those who did, racist hiring practices at the firm level served as a backstop.

The federal government had given its imprimatur to segregated neighborhoods since the beginning of the New Deal with official, written policies that made homeownership much more difficult for Black people. By denying either mortgage insurance to property in neighborhoods with Black residents or mortgages to Black applicants, these agencies translated American racism into financial and real estate code, leading the way for the private sector. City leaders insisted the schools were segregated by coincidence, based on peoples choices of where to live, and there was nothing the Board of Education could or should do to address the situation, aside from building new schools to relieve overcrowding, which really meant building more apartheid schools. Labor unions were free to admit and exclude whomever they chose, and employers hired the same way. Losing out on prospective employment because of the candidates race was difficult to prove, and the burden fell to the victim of discrimination. Most white New Yorkers met suggestions of affirmative action with deep hostility, and with no incentive to do otherwise, employers in the sectors of the economy offering good wages and opportunities for advancement kept reproducing racially homogenous workplaces.