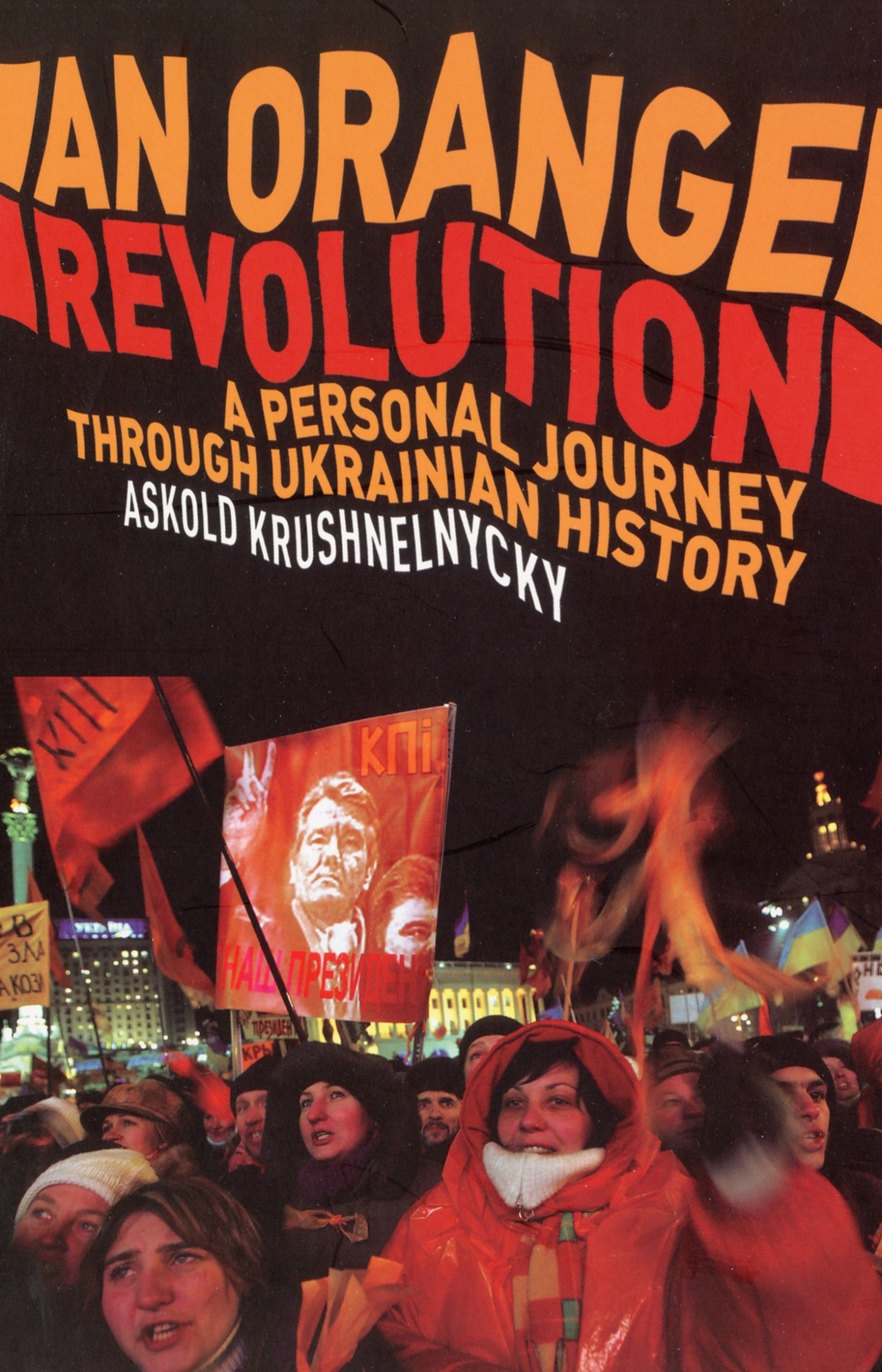

Askold Krushelnycky

An Orange

Revolution

A Personal Journey Through

Ukrainian History

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781446444641

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Harvill Secker 2006

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Copyright Askold Krushelnycky 2006

Askold Krushelnycky has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by

H ARVILL S ECKER

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SWIV 2SA

Random House Australia (Pty) Limited

20 Alfred Street, Milsons Point, Sydney,

New South Wales 2061, Australia

Random House New Zealand Limited

18 Poland Road, Glenfield,

Auckland 10, New Zealand

Random House South Africa (Pty) Limited

Isle of Houghton, Corner of Boundary Road & Carse OGowrie,

Houghton 2198, South Africa

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0436206234 (from January 2007)

ISBN 0436206234

CONTENTS

To my parents and their parents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are many people too many to list them all here who helped me in the writing of this book by sharing their knowledge and providing advice and encouragement. I am grateful to all of them. Particular thanks to my wife, Iryna Chalupa, whose exceptional knowledge of all things Ukrainian was an invaluable resource and whose advice and comments were always wise. Her smiles and support cheered me up and gave me confidence. I also want to thank Ivan Lozowy, Roman Kupchinsky, and Taras Kuzio for their friendly assistance and admirable insights into contemporary Ukraine.

This is the first time I have written a book and fortune dealt me an immensely fine hand in the form of my agent, Kevin Conroy Scott, and editor, Stuart Williams. Kevins sage knowledge and boundless enthusiasm propelled the project forward. Stuarts astute advice was always given gracefully and the subsequent improvements demonstrated the finesse of his skill. I have learned a great amount from both of these new friends.

During my research for this project I read many books and articles which were informative and thought-provoking. Among the books that I found most helpful were Orest Subtelnys outstanding Ukraine A History, Danylo Yanevskys Ukrainian-language Chronicle of the Orange Revolution, and Jaroslav Koshiws Beheaded The Killing of a Journalist. Of considerable use have been an English-language Internet publication called Action Ukraine Report, edited by E. Morgan Williams, and the Ukrainian and Russian-language Ukrayinska Prvada Internet daily newsletter. Both provide comprehensive coverage and analysis of the countrys news and the latter has been a brave champion of Ukrainians fight for democracy.

Chapter One

MOMENT OF TRUTH

In October 2004, Ukrainians knew that the forthcoming presidential election might determine whether their country finally emerged from centuries of slumber, cocooned in repression and tragedy. They had been talking about little else for a year, and all the omens were that it would be a very dirty election: people feared the regime would not shrink from using violence to prolong its corrupt and increasingly authoritarian rule. The sort of techniques used to usurp elections in Third World tinpot republics were already at work, with secret police intimidating and arresting opposition supporters and planting explosives and weapons on them. There would soon be an assassination attempt against the opposition leader and scares about a possible civil war.

When I returned to Ukraine to cover the first round of the election, the country was at a fever pitch of excitement and apprehension. I had covered most of Ukraines presidential and parliamentary elections since the country became independent in 1991 when the Soviet Union disintegrated, but the previous elections had not generated a fraction of the emotion that now crackled in the air of the capital, Kyiv. Ukrainians recognised they were at a historic crossroads: these were the most important elections ever held in their country and the vote would determine whether Ukraine charted a path westwards towards democracy, or whether it would be subsumed in a putative new authoritarian Russian empire.

I had expected to be in Ukraine for several weeks. In the end I stayed for more than three months as the election unfolded into a tense and often dangerous drama that became known as the Orange Revolution. It was also a magnificent and exhilarating time. When television screens carry depressing daily news of war and terror, people crave evidence that the corrupt and the wicked are not invulnerable. The protests in Ukraine provided some inspiring proof. Viewers around the world who had never before heard of Ukraine watched avidly the courageous, graceful and good-natured display of people power. They identified with the protestors, the men, women and children, whose attentive, dignified faces were sometimes creased with laughter and at others streaked with tears; determined faces that seemed fearless but not ferocious. It was easy to admire these genial revolutionaries they were not a mob baying for blood but ordinary, peaceful people from diverse backgrounds who had risked their safety to defend simple ideals of decency and fairness that were readily understood throughout the world.

My entire working life has been spent as a journalist and I have been privileged to cover stories about the hopes, and often savage fates, of people who grasped at ideals so difficult to define, yet instinctively easy to grasp, as democracy and freedom. I have seen civilians standing their ground against ranks of security personnel for these ideas in Kosovo, or enduring prolonged sieges and savage artillery poundings in Croatia and Bosnia. I have witnessed poorly armed and outnumbered fighters under assault from armies with superior weapons in Afghanistan, the Middle East and Nagorno-Karabakh, because they believed freedom and decency were worth making sacrifices for. I have always been captivated by these people of conviction and I have often been sympathetic to them. As events gathered speed in Ukraine in the autumn and winter of 2004 it seemed that violence was almost inevitable and the conflicts I had seen happen in many places elsewhere in the world would happen in Ukraine, the country of my parents.

I was born and raised in Britain but my parents instilled in me a lifelong fascination in, and affection for, Ukraine. Journalists are not supposed to take sides, but in a situation that is loaded with emotions it can be impossible not to, especially if one has come to know a place and its people closely. Objectivity, however, is more than uncritically allowing both sides to have their say, particularly when one of them is a proven liar. But then a journalist can be open to charges of subjectivity if he uses judgment and experience to select facts and comments that he believes accurately reflect, in the space and time available, the essence of what is happening. It is the way the selection is made that distinguishes between propaganda and an attempt at honest reporting. And whilst I have always tried to be an honest reporter, I have frequently been a far from dispassionate observer. The regime that had been in power for a decade in Ukraine was irredeemably bad and getting worse, and my sympathies were firmly with the opposition.