To Kill A Democracy

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Debasish Roy Chowdhury and John Keane 2021

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021938150

ISBN 9780198848608

ebook ISBN 9780192588272

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198848608.001.0001

Printed and bound by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Contents

Theres an old proverb that tells how all nations are slaves to imaginings about their origins, blind pride in their finest hours, pure joy in those moments when its said extraordinary things were achieved that others thought beyond reach. India is no exception to this time-tested truism. The story runs like this: back in the mid-twentieth century, against formidable odds, the people and leaders of India courageously mobilized to snap the chains of imperial domination and set out on the rough road to democracy. They built a democracy thats today not only the planets biggest, but a democracy that breathed fresh life into its ideals and boosted Indias global reputation as a country that survived a murderous Partition, defeated an empire and blessed the fortunes of self-government by its people, and for its people, in radiant style.

Like other national stories, Indias rests on a belief in a beginning that ranks as the beginning of beginnings: that magical moment of birth of Indian democracy, just before sunset on the 14 August 1947, when the Indian tricolour was raised over the old imperial Parliament, to flutter in the late-monsoon Delhi sky, blessed by a distant rainbow. Later that evening, just before midnight, runs the founding story, Jawaharlal Nehru, boyishly slim, dressed in a white achkan with a red rose in his lapel, stood before the Constituent Assembly to declare that the half-century struggle for full independence from British rule was finally over. The four-and-a-half minute speech by Nehru is said to be among the most compelling made by any modern world leader. Nehrus words combined humility with ambition and the yearning, expressed in formal English spoken with an upper-class accent, to start something new in a world broken and battered by war, cruelty, and domination. It is fitting, he said forcefully, into the All India Radio microphone, that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity. The world was now One World, he continued. Peace and freedom had become indivisible. Local disasters now produced global effects. Beginning with India, democracy thus had to be brought to the world, so that power and freedom were exercised responsibly. Long years ago, he said, we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially. He added: This is no time for ill-will or blaming others. We have to build the noble mansion of free India where all her children may dwell.

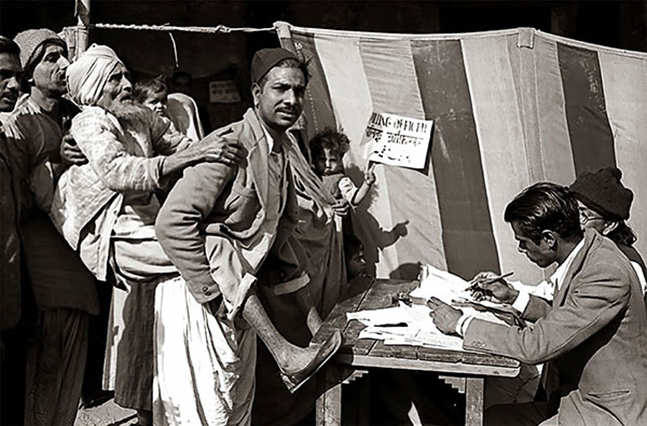

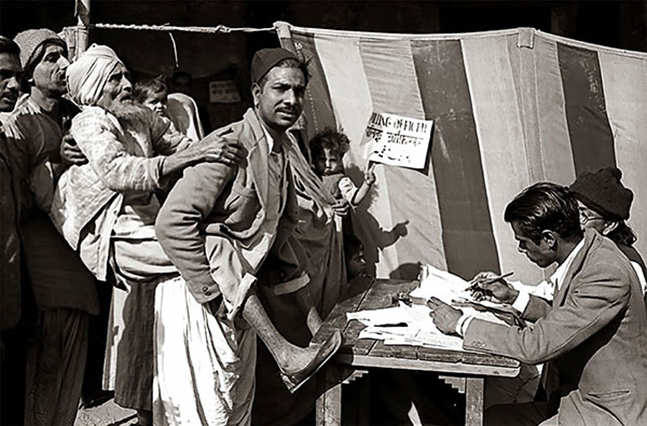

The allegory of Indias tryst with democracy notes the formidable obstacles confronting its transition from a trampled British colony to a proud power-sharing democracy. Nehru and his Congress party envisaged an Asian democracy that wasnt simply a replica of the West. It had to solve two problems at once. The new democracy had to snap the chains imposed from the outside by its colonial masters; and unpick the threads of colonial domination at home by creating a new nation of equally dignified citizens of diverse backgrounds. Democracy was neither a gift of the Western world nor uniquely suited to Indian conditions. India was in fact a laboratory featuring a first-ever experiment in creating national unity, economic growth, religious toleration, and social equality out of a vast and polychromatic reality, a social order whose inherited power relations, rooted in the hereditary Hindu caste status, language hierarchies, and accumulated wealth, were to be transformed by the constitutionally guaranteed counter-power of public debate, multiparty competition, and periodic elections ().

Figure 1. A polling station in Delhi, 1952, during the first general election

Efforts to build an Indian democracy are said to have done more than transform the lives of its people. India fundamentally altered the nature of representative democracy itself. During the first several decades after independence, a new post-Westminster type of democracy resulted, in the process slaughtering quite a few goats of prejudice. None of the standard political science postulates about the prerequisites of democracy survived. They had spoken of economic growth as its fundamental precondition, so that free and fair elections could be practicable only when sufficient numbers of people owned or enjoyed such commodities as automobiles, refrigerators, and wirelesses. Weighed down by destitution of heart-breaking proportions, the country managed to laugh in the face of academic insistence that there was a causalperhaps even mathematicallink between economic development and political democracy. Millions of poor and illiterate people rejected the imperial and pseudo-scientific prejudice that a country must first be deemed materially fit for democracy. Struggling against poverty, they decided instead that they must become materially fit through democracy.

This was a change of epochal significance, say those who tell the India Story, as its been called. In contrast to post-1949 China and many postcolonial countries, Indias transition to democracy did not just show that Mugabe- and Stroessner-style dictatorship and military rule were unnecessary in the so-named Third World. Indian democrats proved that political unity within a highly diverse country could be built by respecting its social differences. They showed, despite everything, that the hand of democracy could come to include potentially billions of people defined by a huge variety of histories and customs that had one thing in common: they were people who were not Europeans, and did not want to be ruled by them. In this way, the region defied the common-sense rule of the white sahibs of Britannia that democracy takes root only where theres a demos bound together by a common culture. Churchill had said so repeatedly. In contrast, say, to the colonies of Australia or Canada, India was the white mans burden, he insisted, a muddled place that was immune to purposeful change in the Western way, which meant that the British were condemned to play the role of custodians of a pagan wilderness in need of law and order. The rescue of India from ages of barbarism, tyranny, and intestine war, and its slow but ceaseless forward march to civilisation constitute the finest achievement of our history, he crowed. Then he grumped. India is an abstraction, he said, a geographical term. It is no more a united nation than the Equator. This fact posed a special difficulty.