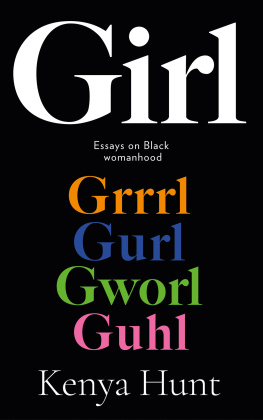

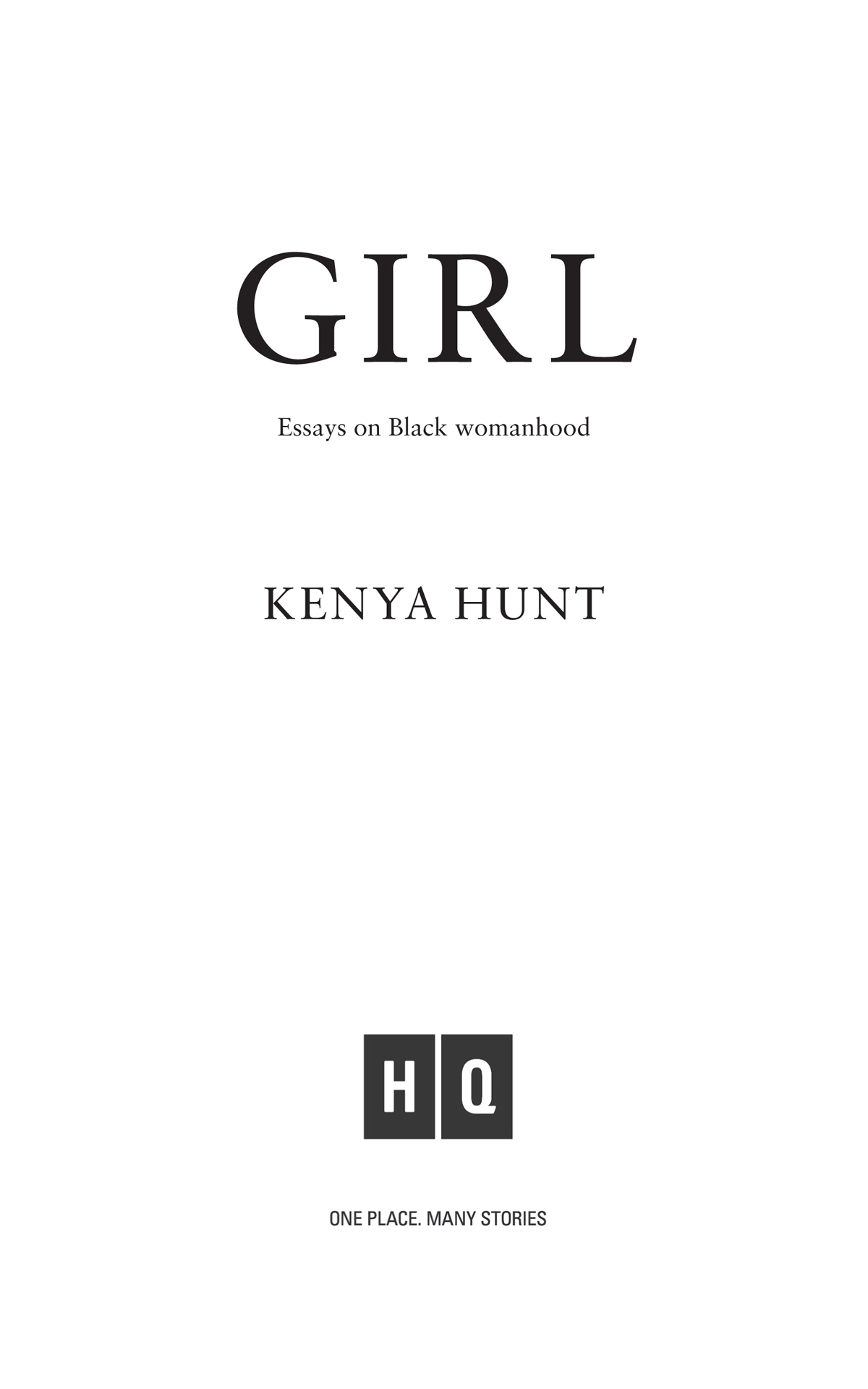

Enlightening, relatable, warm and witty, Girl is a must-read. Sunday Times Style

Girl is an essential, vital and urgent exploration of Black womanhood that should be on everyones reading list. Every page is meaningful and a call for empathy, hope and change. There is such power in the stories that are told, from Kenyas own experience as a mother, as a journalist, as an American in London, to Ebele Okobis essay on the unspeakable loss of a brother to police brutality. If any book should enrich and disrupt your life, let it be this. Harpers Bazaar UK

Powerful, intelligent and thought-provoking. A must read for our times and beyond. ELLE UK

Kenya Hunt provocatively threads cultural observations through relatable stories that illuminate our current cultural moment while transcending it. Refinery29

An essential book to help in becoming an anti-racist ally. Dazed

A provocative, heart-breaking and frequently hilarious collection of original essays on what it means to be Black, a woman, a mother and a global citizen in todays ever-changing world. Glamour UK

Girl speaks to the Black woman of today. Bethann Hardison, model and activist

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First Published in Great Britain by HQ in 2020

Copyright Kenya Hunt 2020

Kenya Hunt asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition November 2020 ISBN: 9780008371999

Version 2020-10-06

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

- Change of font size and line height

- Change of background and font colours

- Change of font

- Change justification

- Text to speech

- Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008371975

For Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland,

Atatiana Jefferson, Aiyana Stanley-Jones,

Tanisha Anderson, Oluwatoyin Salau,

Gynnya McMillen, Korryn Gaines, Riah

Milton, Joyce Curnell, Dominique Fells

Contents

When I started this book, I was on maternity leave with my second son. The freedom of being home all day, every day, and the disorientation of an on-demand breastfeeding schedule oddly suited my writing. It meant that I was awake and journalling during those quiet moments in the night when everyone else was sleeping. I liked the solitude that came with being housebound for large chunks of time with a newborn. After years spent hopped up on adrenaline, it felt good to be off the work treadmill for a moment and to have an opportunity to reassess my life and recalibrate. Not to mention I appreciated having a break to just focus on my family and my writing, uninterrupted by morning commutes, extended work travel and deadlines.

But now, as I complete the book with this introduction more than a year later, Im housebound for a different reason. Were more than four months into a global pandemic, as the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) steamrolls its way through the world, and eight weeks into a nationwide lockdown. The experience of working from home all day, while in a government-enforced quarantine, feels much less like a freedom, though it is most certainly a privilege.

Small acts we once took for granted like shaking a strangers hand, hugging a friend, visiting loved ones or having dinner in a crowded restaurant, are not possible for the foreseeable. Now, we walk down the street wearing face masks, paranoid about who might have coughed just steps before. And we scrub and disinfect our groceries (purchased in a whirlwind of panic after waiting in socially distanced queues that stretch for blocks outside stores) with a rigour that just months ago would have been declared a symptom of obsessive compulsive disorder.

The basics our health, the food on our tables, a walk outdoors, a deep inhale of fresh air now feel like lifes ultimate luxuries. But luxurys meaning changes with context and the pandemic has made the divisions that separate race and class painfully clear.

When the virus hit, a popular line began circulating that 2020 was the end of identity politics, that COVID-19 was the great equaliser that didnt see race or class. People of colour knew better. And the opposite turned out to be true as the news was confirmed. Black, Muslim, Latin and Asian communities were the hardest hit, and women (who make up the vast majority of essential workers) were shouldering the brunt of the load. The virus wasnt wiping the slate clean, it was deepening pre-existing inequalities.

Ive watched close friends lose their loved ones, jobs and mental health to COVID-19. Ive also watched dear friends, forced to reimagine their lives in the face of disruption, begin exciting new jobs, launch innovative new projects, and enter new romantic relationships. Throughout it all, I saw my friends and family more than we had in years, checking in on each other throughout the week on Zoom, FaceTime and Houseparty to make sure we were holding up okay in isolation as sickness, death and a crippled economy inched closer.

And just when it seemed like the news cycle and our collective angst couldnt get worse, we found joy, laughter and solidarity in the most unexpected places. At an enormous, spontaneous Instagram Live party put on by the American DJ D-Nice, I bumped into old friends I hadnt seen in years (old media colleagues, music industry mates and nightclubbing buddies) and the imaginary ones I had only ever followed from a distance (Michelle Obama, Janet Jackson, Rihanna and Tracee Ellis Ross to name a few).

Each one of our circumstances were uniquely different and yet we were all there, 100,000 of us united in isolation and our need for human connection. Weeks later, over 700,000 of us tuned in to a live stream music battle-turned-mutual appreciation session between two women responsible for soundtracking multiple generations of Black lives, Erykah Badu and Jill Scott, and then bonded for the next twenty-four hours over the endless stream of feel-good memes the evening produced. It was a night of sisterhood and healing. A celebration of us, and all our nuances. Most of the time, Id prefer, I like to be a lady. Sometimes, Im not. Im a lot of things. Arent we a lot of things? Jill Scott said. We were all alone, together.

The show of numbers throughout these moments reminded us of our own agency and collective power, especially when the world erupted in protests over the videotaped murder of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man suffocated under the knee of a white police officer. We mobilised on both small local and sprawling global levels. We raised money for bail funds for protestors, called government officials and demanded arrests, and circulated petitions to defund the police. We protested, both in the streets and virtually. And we called out racism as and when we saw it. We said their names: George. Breonna. Ahmaud. Tony. Aiyana. Eric. Michael. Sandra. Tamir. Tony. Tanisha. Yvette. Rekia. Natasha. Kindra. Kimberlee. Joyce. Ralkina. Kayla. Gynnya. Korryn. And we did all of this in a matter of weeks, with black women powering much of the action, from organising marches and conducting justice work trainings to creating social media campaigns and assets that mobilised millions around a range of action plans. Throughout it all, we asserted our beauty and humanity in the face of tragedy, while continuing to go to work, mother our families and support our friends and relatives. We showed up, together.