For my big sister Naomi,

who called me a Groucho Marxist when I was in college.

In short, this left-wing radicalism is precisely the attitude to which there is no longer, in general, any corresponding political action. It is not to the left of this or that tendency, but simply to the left of what is in general possible. For from the beginning all it has in mind is to enjoy itself in a negativistic quiet. The metamorphosis of political struggle from a complusory decision into an object of pleasure, from a means of production into an object of consumptionthat is this literature's latest hit.

Walter Benjamin, Left-Wing Melancholy

Acknowledgments

I cant even begin to formulate a proper thanks to all the people who helped assemble this book of essays. Indeed, given the number of folks involved in this books production, rather than indulge in specifics, Ill try and summarize your value to me in as few words as possible.

First off, I want to thank all of the contributors for putting so much work into their essays. All of you did an absolutely terrific job, using time that wasnt neccessarily yours to give. In between your jobs, partners, and children, you put in an unbelievable amount of effort into this project.

Secondly, I want to thank a number of generous folks who either made themselves available for interviews or allowed us to reprint their work: Naomi Klein, Slavoj Zizek, Wendy Brown, Ramsey Kanaan, Colin Robinson, Giuseppe Cocco, Doug Henwood, Maurizion Lazzarato, and Thomas Frank. Equal gratitude is extended to Michael Hardt for providing us with the fantastic interview with Toni Negri, and to Kathleen Devereaux for the fabulous French-English translation. Aaron Shuman gets ten free dinners in Oakland for all the article-solicitation assistance he provided. And Charlie Bertsch gets the free Sony 17" for his advice, his energy, and the extremely large number of crucial interviews he pulled out of his proverbial hat for this book.

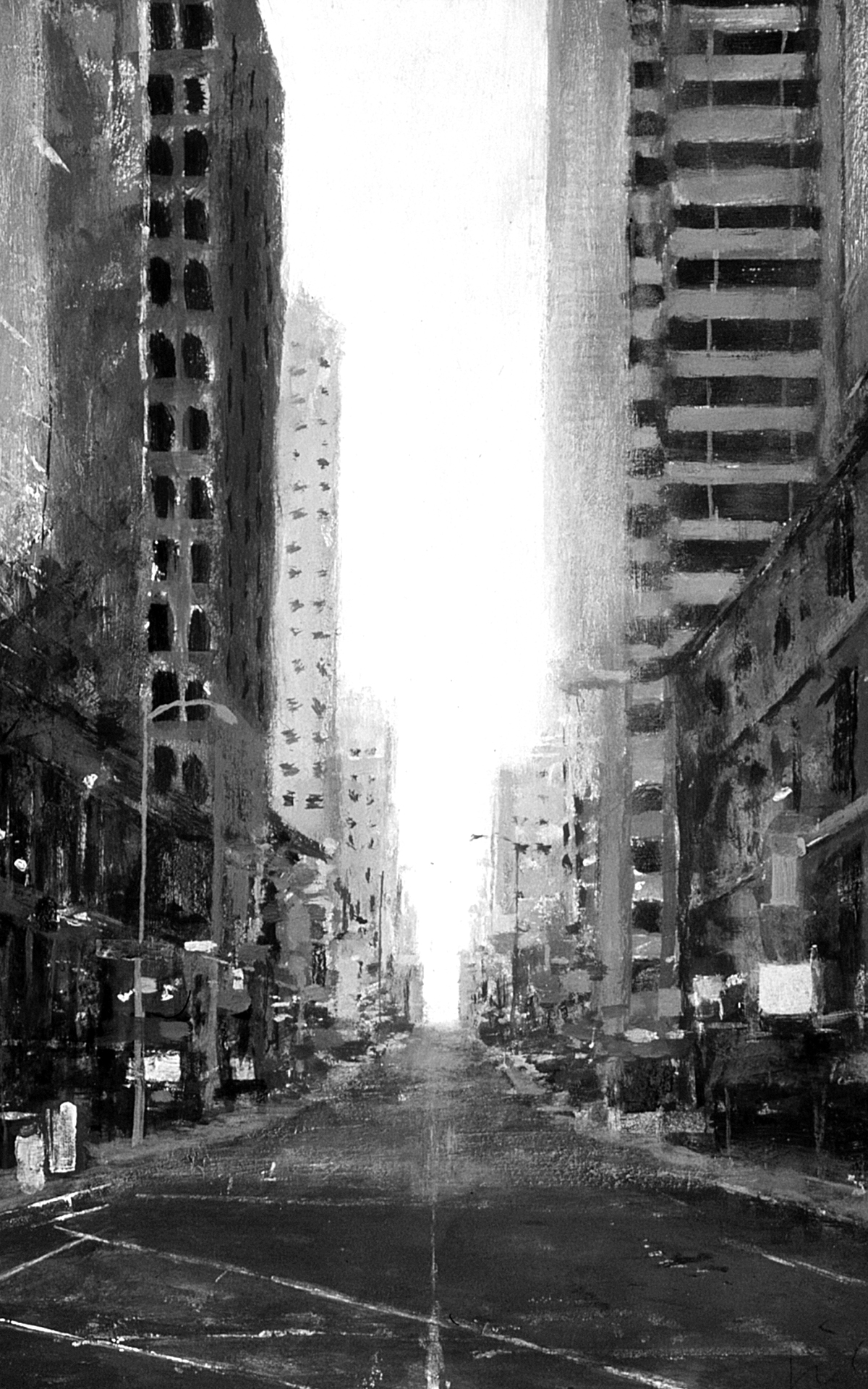

Theres always the subject of presentation to contend with. No collection of excellent political writing would be complete without equally imaginative artwork. Winston Smith made a dream come true when he generously provided us with the faux Norman Rockwell cover image. Having been a fan of his Dead Kennedys/Jello Biafra album jackets since I was a teenager, it was a great honor to have him contribute this image. Also worthy of high praise are photographers Eric Brown, Lisa Knowles, and Ultra-red, painter Jimmy Chen, and performance artist Tim Gordon, who provided wonderful documentary, impressionistic, and incendiary pieces.

Finally, I want to extend deep gratitude to my publisher Johnny Temple, and to this books designer, art director, and contributing photographer, Courtney Utt. This is the second time weve done this in a year, kids. Praise be the two of you for putting up with me and investing so much of your hearts, so much of your time, and every ounce of your patience into our shared projects. I adore and respect the both of you immensely. I think that says it all.

Introduction

W hen I was in the seventh grade, I was fortunate enough to have an older sibling in college to help provide the framework for my own intellectual endeavors. A university senior finishing up a joint degree in Religious Studies and Politics, Naomi had amassed a considerable library that reflected her academic curiosities as a young Jewish leftist. Although I was too young to discriminate between the volumes on her shelves, there were two books with titles that lodged in my mind in the same way that the names of albums circumscribe the imagination of dedicated music fans: Karl Marx and Friedrich Engelss legendary Communist Manifesto, and Rudolf Bahros 1978 work, The Alternative in Eastern Europe.

To this day, I can only begin to surmise why these book titles were so fascinating to me. Perhaps it was because this was the start of the last decade of the Cold War and it was impossible to avoid every name and phrase associated with the conflict becoming a potential gateway to some great realm of ideas. After all, to an inquisitive adolescent living in the United States just before the dawn of the Reagan years, what could have been more compelling than two books outlining the possibilities for utopia from the perspective of communism and the former Soviet Bloc? Even though my reading skills were poor, this much I could intuit. I revelled in the mysterious impenetrability of these two books, knowing somewhere, deep down, that I was holding in my hands the ideological equivalent of forbidden fruit. They felt good. They reminded me of my favorite Black Sabbath records.

It would not be until I actually bought my own copies as an undergraduate student in the late 1980s that Id move beyond the countercultural mystique these rather awkward books held for me and actively try to understand them. By that time, the pro-democracy movement had already started to take root in Eastern Europe, and Bahros anti-Stalinist notion of a third way for socialism would not figure prominently until the mid-1990s, when it became a catch-all phrase employed by former communists in Western Europe to describe their new-found appreciation of the free market.

What are these books about? I once asked Naomi in the spring of 1980.

Oh, she replied, that first book inspired most of the communist revolutions over the past hundred years, and the book by Bahro is about what went wrong, and how a more humane socialism might be achieved.

Looking at the trajectory of my own interests over the years, I find it highly ironic how two volumes I became fascinated with as a teenager came to metaphorically book-end the parameters of my own political thinking, as well as the opinions and perspectives espoused by most of the essays herein. While the historical circumstances informing the basis of this collection are entirely different than those of Marx and Engels during the late 1840s (and those of the German Democratic Republic in the late 1970s), what they have in common is a suspicion about the limitations that market economies impose on peoples freedom, and a decidely heterodox Marxist slant, informed by the varieties of progressive intellectual currents which contributed to the rearticulation of materialist thinking after the 1960s.

The underlying theme which ties this book together is a sense that a healthy respect for democracy requires an appreciation of the forces that inhibit its realization and prevent its logic from being extended to every sector of modern society.

This is not meant to suggest that this book is a nostalgic invocation of Marxism. The Anti-Capitalism Reader is not intended to be a comprehensive representation of the varieties of anti-capitalist movements making themselves felt around the world. To accomplish that task would require a far different, more exhaustive, multi-volume set than this modest collection could ever hope to achieve. Rather, these pieces are contemporary reflections on the role that the market continues to play in our lives, on the ways in which we might construe critical responses to it.

This collection is broken up into four sections. The first, My Definition Is This, concerns itself with defining anti-capitalism. The second, Done By the Forces of Nature, attempts to break down the ways in which some people critically interrogate the political effects of the market in terms of revolutionary social movements; struggles for national self-determination; popular conceptions of the freedoms granted to indviduals by the market; the redefintion of imperialism and sovereignty in a post-9/11 world; as well as the insufficiency of historical discourses about human rights.

Next page