Antisemitism on the Rise includes a broad and engaging array of research and essays, including scholars and practitioners among the writers. The contributions are well grounded in research or experience.

Kevin Spicer, author of Hitlers Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism

Contemporary Holocaust Studies

Series Editors

Ari Kohen

Gerald J. Steinacher

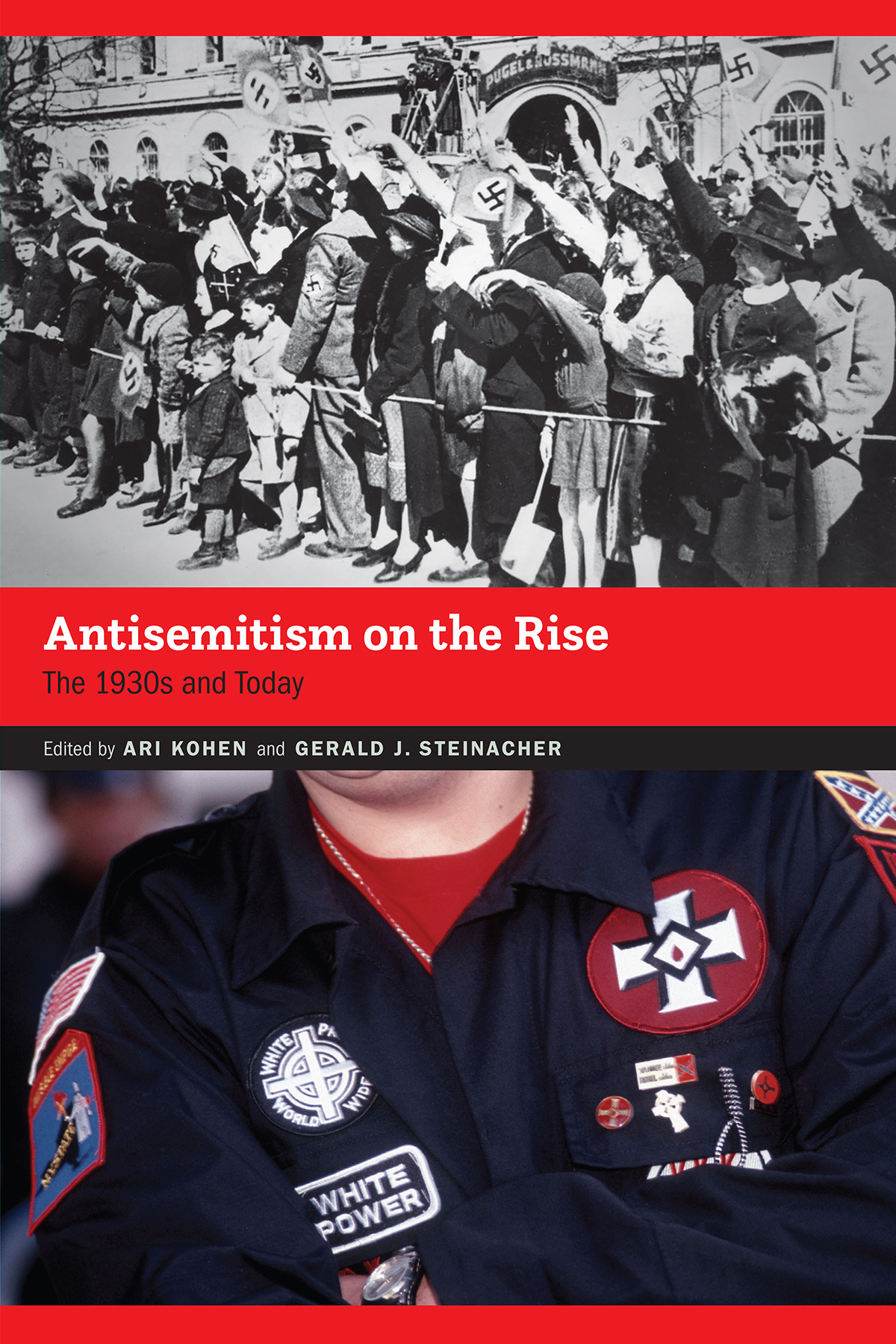

Antisemitism on the Rise

The 1930s and Today

Edited by Ari Kohen and Gerald J. Steinacher

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2021 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover images: top: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy Perquimans County Library; bottom: Alamy/Richard Levine.

All rights reserved

Publication of this important and timely volume was assisted by a donation from Bruce F. Pauley, professor emeritus of history at the University of Central Florida, and his wife, Marianne Pauley.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kohen, Ari, 1977, editor. | Steinacher, Gerald, editor.

Title: Antisemitism on the rise: the 1930s and today / edited by Ari Kohen and Gerald J. Steinacher.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2021] | Series: Contemporary Holocaust studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020057443

ISBN 9781496226044 (paperback)

ISBN 9781496228468 (epub)

ISBN 9781496228475 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : AntisemitismHistory20th century. | AntisemitismHistory21st century. | AntisemitismStudy and teaching.

Classification: LCC DS 145. A 6335 2021 | DDC 305.892/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020057443

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

Ari Kohen and Gerald J. Steinacher

Joseph W. Bendersky

Jean Cahan

Jrgen Matthus

Timothy Turnquist

Leonard Greenspoon

ukasz W. Niparko

R. Amy Elman

Shlomo Abramovich

Scott B. Littky

Ari Kohen and Gerald J. Steinacher

People all across the United States went to sleep on the night of August 11, 2017, with the sense that something about their country had been fundamentally altered. Earlier in the evening a conglomeration of far-right white supremacists groups, alongside members of the so-called alt-right, marched through the campus of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville carrying torches and chanting neo-Nazi slogans. It was a watershed moment, even for a country whose most politically conscious citizens felt radically divided from one another by the 2016 election of Donald Trump to the presidency on a campaign characterized by racist and antisemitic dog whistles. This feeling, of living in a divided and much-changed America, existed even before the murder of Heather Heyer by a white supremacist who drove his car into a crowd of counterprotesters the next day. Indeed, in announcing his campaign for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, former vice president Joe Biden released a video in which he referred to the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville as a defining moment for the nation.

The torchlit march was the unannounced opening of this rally, scheduled for August 12, whose organizers intended, broadly, to unify the white nationalist movement and, specifically, to protest the planned removal of the statute of Confederate general Robert E. Lee from Charlottesvilles Lee Park (now Emancipation Park). But while the earlier events drew dozens of white supremacists, the August rally was intended to bring together many hundreds of members of disparate groups from across the countryincluding the Klan; the National Policy Institute; Identity Evropa; neo-Nazi groups such as Vanguard America, Traditionalist Workers Party, and the National Socialist Movement; neo-Confederate groups such as Identity Dixie and League of the South; and othersthat all held a common belief in white supremacy.

Given the makeup of the rallys participants, it is interesting to look back from the distance of a few years and to wonder why anyone was surprised by what took place. What made the August 11 march such a watershed moment? Everyone knew that the people who descended on Charlottesville werent history buffs who cared deeply about Confederate monuments as symbols of American history. They were members of fringe groups who focused on white identity and who trafficked in fantasies about a restoration of the primacy of white Christians in America. Racial resentment and white grievance were expected from the speakers at the August 12 rally. What was unexpected, on the evening of August 11, was the unmistakable feeling of looking through a window into 1930s Weimar Germany, where everyday citizens, not simply the well-known racists, were comfortable marching through the streets chanting about their hatred of minority groups. Here, on the campus designed by Thomas Jefferson, were young men, well-dressed in khaki pants and white button-down shirts, marching and chanting messages of hatred. The mask had fallen off and the bigotry that had been covered by what suddenly looked like the thinnest veneer of respectability was on display for anyone who cared to look. The violence that followed immediately seemed predictable and obvious.

The expectations, prior to that torchlit march, were that the participants who traveled to Charlottesville were racists, and that their support for Confederate monuments was linked to their white identitarian beliefs. As such, their chanting of White lives matter! as they marched made sense to the people who watched on social media in real time as the march unfolded. But then the marchers began to chant the Nazi slogans Blood and Soil! and Jews will not replace us! The connection between racism and antisemitism was so surprising and seemingly bizarre that, in the initial media rundowns of the march, reporters published accounts in which they reported that the marchers chanted You will not replace us!

Replacement theory, the conspiracy that provides structural support for a good deal of the white supremacist activism we see today, can be traced back to antisemitic conspiracy theorizing in France in the late 1800s that imagined a Jewish plot to bring about the downfall of white, Christian Europe through miscegenation. The best-known version is douard Drumonts 1886 La France Juive, an immensely popular two-volume work that presaged not only Nazi antisemitic literature but also the contemporary work of Renaud Camus, Le Grand Remplacement, in which todays Muslim immigrants stand in for the Jews of Drumonts France. It was the same concept that motivated Robert Bowers to bring multiple weapons into the Tree of LifeOr LSimcha Congregation in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on October 27, 2018 and murder eleven Jewish worshippers, the deadliest attack on Jews in American history. In the weeks before the mass shooting, Bowers, a white supremacist who had been active on the fringe social media website Gab, complained that President Donald Trump was surrounded by too many Jewish people and blamed Jews for helping migrant caravans in Central America.

But perhaps the most alarming aspect is not simply that white supremacist terrorism is on the rise; its that replacement theory has been mainstreamed over the past few years so that people like Bowers hear their own beliefs spoken by those who reside at the pinnacle of power and influence. After another mass shooting committed by a white supremacist in El Paso, Texas, in 2019, the

Next page