Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

RACIALIZED MEDIA

Racialized Media

The Design, Delivery, and Decoding of Race and Ethnicity

Edited by Matthew W. Hughey and Emma Gonzlez-Lesser

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2020 New York University

All rights reserved

References to internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hughey, Matthew W. (Matthew Windust), editor. | Gonzlez-Lesser, Emma, editor.

Title: Racialized media : the design, delivery, and decoding of race and ethnicity / edited by Matthew W. Hughey and Emma Gonzlez-Lesser.

Description: New York : New York University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019041704 | ISBN 9781479811076 (cloth) | ISBN 9781479814558 (paperback) | ISBN 9781479807826 (ebook) | ISBN 9781479859924 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mass media and race relations. | Mass media and minorities.

Classification: LCC P94.5.M55 R35 2020 | DDC 302.23089dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041704

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

For Menaka, Bianca, Noa, and Liev

CONTENTS

- Matthew W. Hughey and Emma Gonzlez-Lesser

- Minjeong Kim and Rachelle J. Brunn-Bevel

- Catherine R. Squires and Aisha Upton

- Maretta McDonald

- Rachel Kuo

- Martin Gilens and Niamh Costello

- Justin de Leon

- Christopher Chvez

- Carlos Alamo-Pastrana and William Hoynes

- SunAh M. Laybourn

- Leslie Kay Jones

- Nadia Y. Flores-Yeffal and David Elkins

- Sonita R. Moss and Dorothy E. Roberts

- David J. Leonard

- Michael L. Rosino

- Tina M. Harris, Anna M. Dudney Deeb, and Alysen Wade

- Emma Gonzlez-Lesser and Matthew W. Hughey

Introduction

The Labor of Racialized Media

Stuart Hall and the Circuit of Culture

MATTHEW W. HUGHEY AND EMMA GONZLEZ-LESSER

In September 2018, the tennis star Serena Williams lost the final of the US Open to Naomi Osaka after receiving three code violations from the chair umpire. Williams was outspoken and expressive during the match, accusing the chair of unfair and biased calls and calling him a thief. Depicting the event, the veteran Australian cartoonist Mark Knight drew a cartoon showing Williams stamping on her racquet, with a babys pacifier on the ground nearby, and the umpire asking Osaka, Can you just let her win? The cartoon was published in the Australian-based Herald Sun. There was an eruptive response around the globe. The Irish Times asked, Outrage-mongering or old-fashioned racism? (OConnell 2018). A Washington Post article said the cartoon used dehumanizing facial features, while Brenna Edwards, a Black journalist who reports for Essence magazine, said that the cartoon dates back to the Jim Crow era. You have Serena in the foreground as a hulking mass, not even looking like a human (ABC News 2018). Knight rejected such characterizations and stated, I find on social media that stuff gets shared around. It develops intensity way beyond its initial meaning. No racial historical significance should be read into it (ABC News 2018).

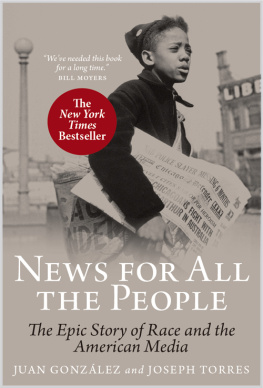

The incident reveals the social import of the concept of race and its relationship to varied mass media. From streaming broadcast tennis matches to newspaper cartoons, from journalism to social media debates, meaning-making and contestation over race and racism are pressing concerns of the media world (Hunt 1997). Such constructions and discourses are additionally imbued with notions of difference, identity, representation, inequality, power, agency, and ethics, gesturing toward how unsettled and uneasy the place of race is across a media-saturated globe.

For decades now, scholars have empirically investigated the influence of media exposure in issues related to race and racism and have cataloged how media impacts our thinking, emotions, and behaviors. Importantly, ample evidence shows how the manner of ethnic and racial representation in the media can result in either harm or benefit for different groups. For example, Patricia Hill Collinss notion of controlling images in Black Feminist Thought (1990), John Downing and Charles Husbands Representing Race (2005), Stephanie Greco Larsons Media and Minorities (2005), and Elizabeth Ewen and Stuart Ewens Typecasting (2011) are all landmark studies that concentrate on the frequency of racial depictions that litter the mediascape. Yet much less scholarship and fewer conclusive takeaways have been generated concerning the media production, regulation, and consumption of these representations. As such, the authors of the chapters in this book directly address the social dynamics that underpin the design, delivery, and decoding of the intersection of race and media.

What Is Race? What Is Media?

We take the social scientific constructionist approach that race is a meaningful category of human difference by virtue of the social significance with which it is imbued. That is, the concept has no biological validity, essence, or inherent ability to determine our lives (Morning 2014). From sociology to biology and from genomics to anthropology, experts in these fields do not deny that clusters of human populations carry particular genetic information. But clusters of genetic material do not provide the basis for social distinctions that society recognizes as race. As the sociologists Karen Fields and Barbara Fields (1994, 113) put it, Anyone who continues to believe in race as a physical attribute of individuals, despite the now commonplace disclaimers of biologists and geneticists, might as well also believe that Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny and the tooth fairy are real, and that the earth stands still while the sun moves. Even Craig Venter, one of the first scientists to map the human genome, stated, The concept of race has no genetic or scientific basis (Weiss and Gillis 2000, A1).

Race is, however, a social fact (Bonilla-Silva 1999). It operates over myriad social dimensions as powerful ideologies and dominant and central social institutions, through group interests and personal identities, and within the scope of everyday interactions (Hughey 2015; Roth 2016; Morning 2017). What we recognize as racial depends on arbitrarily selected and defined phenotypes, as well as practices, beliefs, customs, and many other random criteria we use as evidence. Importantly, the concept of race was birthed in the service of colonialism as a rationale for dominance and inequality. In many ways, the concept still serves that purpose, and racial inequality has become a hallmark of modern society and a scathing reminder of the hypocrisy of modernity. Simply put, Race is a biological fiction with a social function (Hughey 2017, 27).