AFTER EIGHT years spent trying to understand General Husayn and his vanishing Ottoman-Tunisian world, it is my great pleasure to thank the institutions, colleagues, and friends who have been instrumental in the realization of this book.

For their tremendous support, I am indebted to the following institutions: Princeton Universitys Department of Near Eastern Studies and Department of History, the William Hallam Tuck Memorial Fund Summer Research and Travel Grant, and the Learned Travel Society Fund; the Department of Arabic Studies at INALCO (Paris); the European University Institute in Florence, where this research project was born in 2009 and where the first three chapters were written in 2015 thanks to a Braudel Fellowship; the Ecole Franaise in Rome, which has been a safe haven for writing the three last chapters; and the Institute of Advanced Studies in Paris.

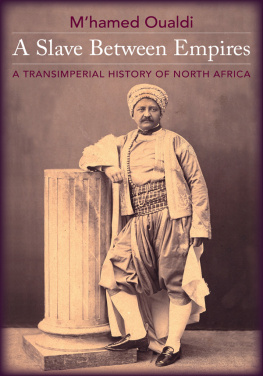

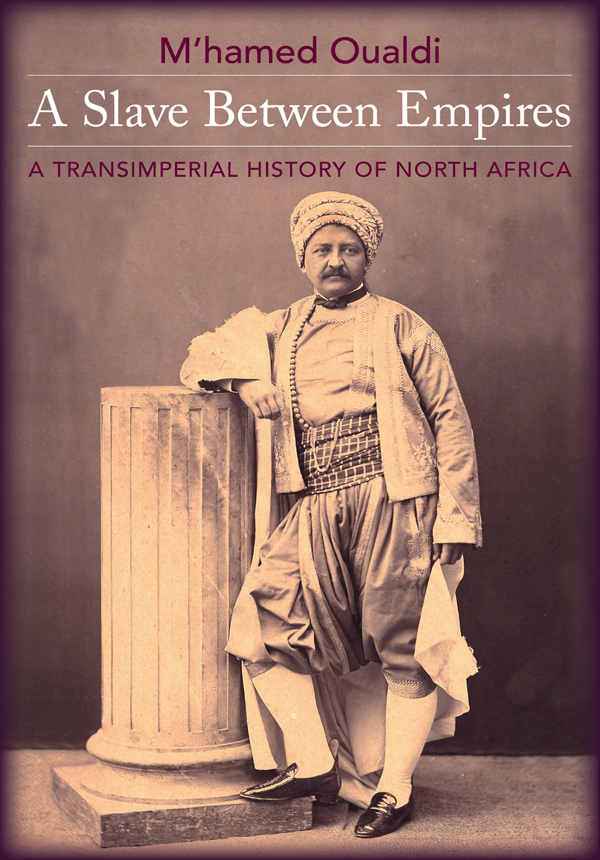

I also want to express my deep gratitude to the archivists and librarians who facilitated access to primary sources at the Archives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs in La Courneuve and Nantes, the French National Archives in Aix-en-Provence, the Public Record Office in London, the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, the Archives of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Rome, the State Archives in Florence and Lucca, the Tunisian National Library, and the Tunisian National Archives, where I could always count on the help and expertise of my friend and colleague Mabrouk Jebahi. I am also grateful to Youssef Ben Smail for sharing a file from the Ottoman consul in Florence that he found at Babakanlk Osmanl Arivi in Istanbul. Habib Bouhageb provided invaluable documents, information, and pictures from his private collection, including the fascinating picture used for this book cover: a portrait of Husayn taken by the famous Parisian photographer Felix Nadar.

During a five-hour defense and workshop in December 2016, the first version of this manuscript, written in French, greatly benefited from the critical insights and generous comments of Fatma Ben Slimane (Tunis I University), Olivier Bouquet (Paris-Diderot University), Catherine Brice (Paris Est Crteil-Val-de-Marne University), Simona Cerutti (EHESS-Paris), James McDougall (Oxford University), and Jocelyne Dakhlia (EHESS-Paris), to whom I owe particular thanks for her tremendous help, encouragement, and the thoughtful comments she tirelessly provided, page after page and chapter after chapter.

Adrian Morfee translated the first version of the manuscript into English during summer 2017. Some sections were presented at various conferences and venues, where Etty Terem (Rhodes College), Pascal Menoret (Brandeis University), Jane Hathaway (Ohio State University), Fahad Ahmad Bishara (University of Virginia), and Emmanuelle Saada (Columbia University) provided constructive and engaging feedback. Particular thanks are owed to Michael Laffan, Molly Green, Linda Colley, Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Skr Hanioglu, Michael Reynolds, William Chester Jordan, Max Weiss, Cyrus Schayegh, Phil Nord, and all of my colleagues in the departments of History and Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University, who shared their questions and comments after presentations of this project or after having read chapters of the translated manuscript.

I am grateful to my editor at Columbia University Press, Caelyn Cobb, for having understood the project, its use of microhistory, and its intervention in the historiography of North Africa. Monique Briones, Susan Pensak, and Ben Kolstad were also instrumental in the production of the book. My heartfelt appreciation goes to the two anonymous reviewers who provided invaluable advice for revising, restructuring, and rewriting the manuscript. At this stage, S. C. Kaplan was also instrumental in copyediting the revised English version of the manuscript. Troy Tice and Jakub Novk read the revised version. As always, my colleague Nilfer Hatemi has been more than generous with her time, translating three documents from Ottoman Turkish into English for me.

To complete this project, over the years, in North America, North Africa, and Europe, I was able to count on the support of students, colleagues, close friends, and thoughtful people.

At Princeton, since 2013, these include Muriel Cohen and Emmanuel Szurek, Eugenia Palieraki and Angelos Dalachanis, Jessica Metcalf and Sean McMahon, Elsa Devienne, Julien Ayroles and Sarah Kocher, Samia Henni and Pascal Schwaighofer, Miriam Lowi and Abdallah Hammoudi, Sadaf Jaffer and Dan Sheffield, Lara Harb and Fulvio Domini, Giulia Puma and Guillaume Calafat, Jonathan Gribetz, the admirable Lucette Valensi and Abraham Udovitch, Jakub Novk, and my dearest friend Nadia Benabid, all of whom reminded me that there is a life outside of campus and academia, inviting me and my partner to their warm places for lavish dinners and lively discussions. I am also more than indebted to the efficient staff of our departments, especially to Bill Blair, who has read and edited my papers and chapters. I have learned from many of the students who enrolled in my classes, particularly from Yasmina Aidi, Edna Bonhomme, Brahim Guebli, Peter Kitlas, Joshua Picard, Matthew Schumann, and Julian Weideman, with whom I have worked closely on their fascinating projects in recent years.

In Tunis, I had the chance to discuss Husayns legacies with Anne-Marie Planel and Sadok Boubaker, Kmar Bendana and Khaled Kchir, Fatma Ben Slimane, Sami Bargaoui, and Isabelle Grangaud, who has been hugely influential in reshaping my understanding of nineteenth-century North Africa, the issue of archives, and the notion of context. On the other side of the Mediterranean, Muriam Davis, Thomas Serres, Nadia Marzouki, Marie, Luca, Valentina, Sasa, and Ariana illuminated my stays during two semesters in Florence and Rome. For this research project, I learned a great deal from Catherine Mayeur-Jaouen, Julia Clancy-Smith and Amy Kallander.

I have enjoyed every minute of my discussions with my colleagues and friends Camille Lefebvre and Natividad Planas, and my friend Marie Fradet, who was kind enough to quickly edit the French manuscript. But in each and every one of these places, nothing would have been the same without the understanding and support of Augustin, to whom I dedicate this book.

Archival Collections and Libraries Consulted

Aix-en-Provence

Archives Nationales dOutre-Mer. Algeria 1H29, 26H13 (10), 26H13 (11).

Courneuve

Ministre franais des Affaires trangres (Courneuve). Correspondance politique et commerciale 18861917. Tunis files 1, 93, 460, 462, 602, 62728, and 62930 (Husayns legacy).

Florence

Archivio di Stato: Repertorie sentenze corte dappello 188689.

Archivio Notarile Provinciale: Registers 24045.

Istanbul

Babakanlk Osmanl Arivi: HR.H171/13.

Livorno

Archives of Livorno: Birth Certificate Register.

Biblioteca Labronica.

London

Public Record Office, Foreign Office 335/166; FO 102/170, 171, 172; FO 881/5594.

Lucca

Archivio di Stato.

Nantes

Ministre franais des Affaires trangres. Tunisia boxes 31215, 9012, 1071, 1179, 1180, 1211a, 1217, 1477, 1488, 1495; Florence boxes 12, 100, 100bis; Livorno boxes 13133; Istanbul boxes 80, 84.

Rome

Ministero degli Affari Esteri, Archivio storico registers 122325, 143945.