Televised Redemption

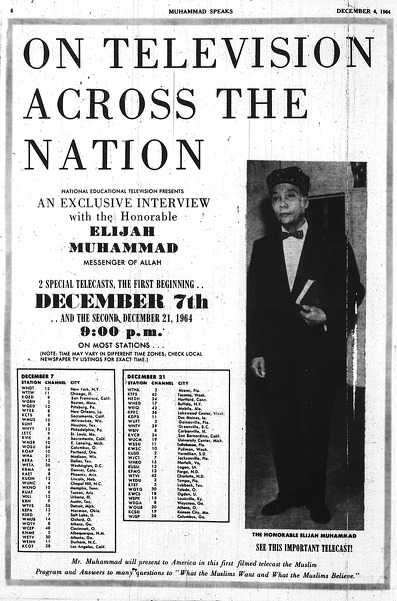

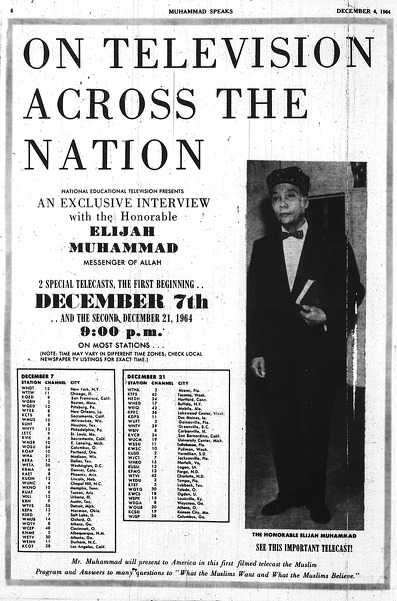

Muhammad Speaks, December 1964. This here is one of our best ministers.... You shouldnt throw away truth. If no one will buy it, just take it back home and give it away. Elijah Muhammad discussing the value of the Nation of Islam newspaper (quoted in The Messenger of Allah Speaks on the Importance of the Muhammad Speaks Newspaper, Nation of Islams Women Committed to Preserving the Truth, www.noiwc.org).

Televised Redemption

Black Religious Media and Racial Empowerment

Carolyn Moxley Rouse, John L. Jackson, Jr., and Marla F. Frederick

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2016 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rouse, Carolyn Moxley, 1965 author.

Title: Televised redemption : Black religious media and racial empowerment / Carolyn Moxley Rouse, John L. Jackson, Jr., and Marla F. Frederick.

Description: New York : NYU Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016023929| ISBN 978-1-4798-7603-7 (cl : alk. paper) | ISBN 978-1-4798-1817-4 (pb : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansReligion. | Religion on television. | Television broadcastingReligious aspects. | Television in religionUnited States.

Classification: LCC BR563.N4 R68 2016 | DDC 200.89/96dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016023929

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

This book would have been impossible without the incredible generosity of the many interlocutors with whom the three of us have worked over the years. Thanks to all the people who have graciously and courageously allowed us to examine their spiritual/religious beliefs and practices in our attempt to understand Africana religio-political possibility. Thank you for your time, meals, rides, and spare rooms. You were our teachers. Thank you, Jennifer Hammer at New York University Press for being willing to work with us on this projectand for always providing us with valuable feedback and encouragement. Thank you, Constance Grady and Alexia Traganas for your stewardship bringing the book to press. And thanks to the anonymous readers who helped us revise and clarify some of our claims. Diana Burnett, Carleigh Beriont, and Jasmine Reid helped us to prepare the final draft of this manuscript for submission. Thank you for your meticulous efforts. Finally, we want to thank our families, colleagues, and friends, whose counsel, company, and feedback have been critical throughout.

In Plessy v. Ferguson, the 1896 Supreme Court case affirming the legality of racial segregation in the United States, Justice Henry Billings Brown made a most extraordinary claim in his draft of the majority opinion. His legal argument was predicated on the belief that racism is natural and, therefore, not something the courts can effectively adjudicate:

Legislation is powerless to eradicate racial instincts or to abolish distinctions based upon physical differences, and the attempt to do so can only result in accentuating the difficulties of the present situation. If the civil and political rights of both races be equal, one cannot be inferior to the other civilly or politically. If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.

In the long, drawn-out march toward full citizenship, African Americans have had to push back against what Brown called racial instincts.

Humanization necessitated struggles over representation and recognition. Blacks had to find a way to write their own stories, define their own identities, and rearticulate concepts of justice in light of human difference.

Slavery, Jim Crow, convict leasing, and mass incarceration were all predicated on the idea that blacks were less intelligent, less moral, and less capable of pro-social behavior despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Notably, commonsenseness, a term capturing how we see our cultural beliefs as natural and irrefutable facts, continues to be the way by which black inferiority is made real. In hindsight, Justice Browns argument that racism is instinctually just seems outrageousat least it should. As a cultural process, race-making remains, for most, hidden in plain sight. As a result, race as a category of difference is naturalized and dehistoricized, with the construction of whiteness representing a vivid case in point. If we trace education, health, wealth, and incarceration disparities to these unmarked norms, we can recognize how assumptions about biological and cultural difference impact the ways in which people are treated and defined.

The dehumanization and reclassification of blacks as fundamentally different and/or inferior did not end with the Supreme Courts 1954 Brown v. the Board of Education desegregation ruling. Some writers continue to argue that genes and behavior mark clear borders between races, while others use culture of poverty arguments to explain contemporary racial inequalities of outcome and possibility. Many of these same writers are housed in elite think tanks and academic institutions, and often contribute to newspaper op-eds and television news talk shows. Notably, racial commonsense has continued to animate political discourse well into the twenty-first century, even though the majority of social scientists understand race to be a product of history as opposed to biology or cultural pathology. Regardless of how many Americans consider the race question settled in the United States, for the religious communities considered in this book, the project of redeeming the race through media has continued to be an urgent priority.

The purpose of this book is to demonstrate the powerful role black religious media has had since the eighteenth century in not only marking unmarked racial norms, but in altering racial instinct. Black religious media continues to challenge the taken-for-granted notions of white and European superiority not from a position of science and reason, but from a position of morality and justice. It has been central in humanizing African Americans, such that by the twenty-first century, around 40 percent of white voters chose a black president. We certainly do not argue that the election of a black president has marked an end point in the trajectory toward a post-racial America. Instead this book focuses on what black religious media has done to open a space for reconsidering what race means and for promoting racial justice.

Most historical representations of the struggles for racial justice avoid discussions of the critical subjective work required to change minds. Our goal as anthropologists in this book has been to unearth the motivations for the radical attitudinal changes toward race and racial identity

Next page