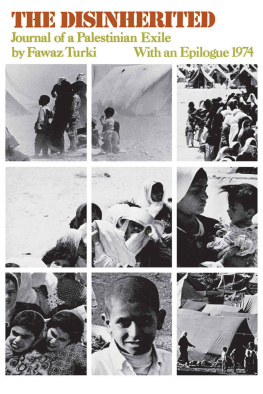

Fawaz Turki - The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248)

Here you can read online Fawaz Turki - The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1972, publisher: Monthly Review Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248)

- Author:

- Publisher:Monthly Review Press

- Genre:

- Year:1972

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Thank you for buying this ebook, published by NYU Press.

Sign up for our e-newsletters to receive information about forthcoming books, special discounts, and more!

Sign Up!

A publisher of original scholarship since its founding in 1916, New York University Press Produces more than 100 new books each year, with a backlist of 3,000 titles in print. Working across the humanities and social sciences, NYU Press has award-winning lists in sociology, law, cultural and American studies, religion, American history, anthropology, politics, criminology, media and communication, literary studies, and psychology.

The Disinherited

Journal of a Palestinian Exile

by Fawaz Turki

Copyright 1972 by Fawaz Turki

All Rights Reserved

ISBN-10 0-85345-248-2

ISBN-13 978-0-85345-248-5

Monthly Review Press

146 West 29th Street, Suite 6W

New York, New York 10001

www.monthlyreview.org

The major source for this book is my own recollections of what we have endured and my own conviction that ours is a just cause, a cause long forgotten by the Western world (self-righteous in its overly easy conscience) and long mutilated by the Arab world (self-satisfied in its mercenary games).

Consequently this is not an objective work. It is however a sincere narration of a phase in the history of the Palestinian people and of their response to the challenge of adversity that has confronted them over the past two decades. As I lived that phase and took a part in that response, what I have to say, subjective though it is, may offer some notes toward an understanding of what we are doing now and an insight into the why and the how of it.

I am neither concerned nor qualified to indulge in the game of quote and counter-quote adopted by those whose business or ideology drives them to espouse the position of one or the other. I have discovered that with enough diligence, the historian can present a devastatingly convincing version of the Zionist/Israeli/Jewish (call it what you wish) claim in modern Palestine. Another historian, with equal reserves of diligence and partisan to our own claims and grievances, can come up with a perfectly valid and at the same time diametrically opposite view.

The vexatious issue, as the problem of my people was called during the Truman and Mandate years, has now expanded and become the Arab-Israeli conflict; and it is felt that the solution of it by the big powers is as mandatory now as it was mandatory then.

Mine is not a vexatious issue, nor has it much to do with the conflict now raging between the Arabs and the Zionists. Nor is its solution dependent upon, nor will I allow it to be, the whims of the big powers. Mine is an existential problem having to do with the yearning for my homeland, with being part of a culture, with winning the battle to remain myself, as a Palestinian belonging to a people with a distinctly Palestinian consciousness.

If I was not a Palestinian when I left Haifa as a child, I am one now. Living in Beirut as a stateless person for most of my growing-up years, many of them in a refugee camp, I did not feel I was living among my Arab brothers. I did not feel I was an Arab, a Lebanese, or, as some wretchedly pious writers claimed, a southern Syrian. I was a Palestinian. And that meant I was an outsider, an alien, a refugee and a burden. To be that, for us, for my generation of Palestinians, meant to look inward, to draw closer, to be part of a minority that had its own way of doing and seeing and feeling and reacting. To be that, for us, meant the addition of a subtler nuance to the cultural makeup of our Palestinianness.

The experience of our growing-up yearsblame that experience on the Arab governments, blame it on the UN, blame it on God, for the cabalistic interpretation of political events does not interest mehas decidedly ravished our beings. It ravished the law and the order of the reality that we saw around us. It defeated some of us. It reduced and distorted and alienated others.

The defeated, like myself, took off to go away from the intolerable pressures of the Arab world to India and Europe and Australia, where they wrestled with the problem and hoped to understand. The reduced, like my parents, waited helplessly in a refugee camp for the world, for a miracle, or for some deity to come to their aid. The distorted, like Sirhan Sirhan, turned into assassins. The alienated, like Leila Khaled, hijacked civilian aircraft.

If there are still people around who call us Arab refugees or southern Syrians or terrorists, who want to subdue us, who want to resettle us, who want to ignore us and who want to play games with our destiny, then they are not tuned in to the vibrations and the tempo of the Third World, of which the Palestinians are a part.

Every writer and speaker wants to win his audience to his point of view, a point of view that is carried along by the weight of its supposed impartiality. I have no point of view to make. And I cannot pretend to begin to be impartial.

When I was a child, a few weeks after we left Palestine in 1948, I used to sit with a crowd of people at the camp, mothers and fathers and aunts and grandparents and young wives and children, to listen to the radio at precisely three oclock every day. The voice from Radio Israel (or Radio Tel Aviv, or whatever damn name it had) used to come on to announce The Messages. Silence would fill the space around us. Tension would grip even the children. From Abu Sharef, and Jameela, Samir and Kamal in Haifa, the words would come across the air. To our Leila and her husband Fouad. Are you in Lebanon? We are all well. A few moments pause, then: From Abu and Um Shihadi, and Sofia and Osama to Abu Adib and his family. Is Anton with you? We are worried. The dispassionate voice continues: From Ibrahim Shawki to his wife Zamzam. I have moved to Jaffa. Your father is safe with us.

One whole hour of this. During it an outburst of tears at the knowledge that loved ones are well. Despair that a relative is not yet located. Hope that in tomorrows broadcast a good word may be heard. Then a trip on the bus to the Beirut station to queue up at the message office to send your own twenty-six words across the ether to the other side. Because you could not go over there yourself to say them. Because an armistice line was drawn as a consequence of a war you did not understand, did not want, did not initiate.

A few years later, we were still in that refugee camp on the outskirts of Beirut where life was becoming harder and existence becoming more futile. The Lebanese authorities, conscious of the image of their capital as a Western city, made attempts to move our camp, as far away as they could, to avoid offending foreign visitors with the sight of it. Our camp was on the way to the airport.

For bureaucratic or other reasons, the initiative failed. But no one at the Ministry of the Interior, and no one in any editors office, bothered to consider or write about the hardship we would have endured had we in fact been moved forty miles out of town. Or the disruption this might have caused in the lives of children going to school, men going to work, the sick going to their doctors, and the women going to their shops. Or the indignity to a people already devastated by one uprooting from their homeland.

The story of these years is thus not offered as a point of view. It is not written with objectivity. Nor in the telling do I hope to win adherents to my cause. I merely wish to isolate our problem from the Arab-Israeli dispute, identify it and describe it in its human dimensions, for those who wish to know what it was like, what it will be like.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248)»

Look at similar books to The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Disinherited (Mr Modern Reader PB-248) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.