MMMM

This page intentionally left blank

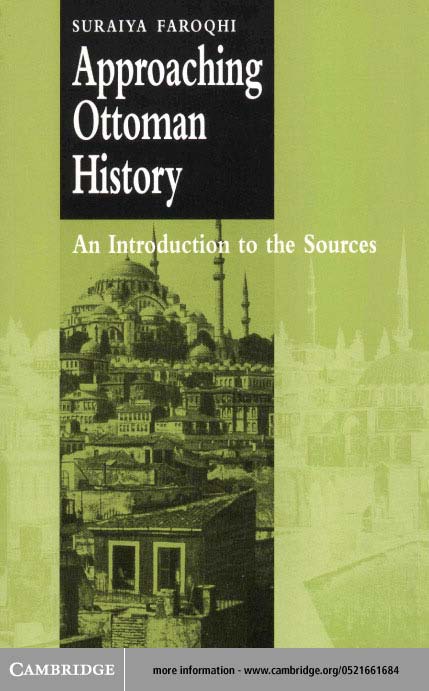

Approaching Ottoman History

An Introduction to the Sources.

Suraiya Faroqhi is one of the most important economic and social historians of the pre-modern Ottoman empire writing today. Her scholarly contribution to the field has been prodigious. Her latest book, ApproachingOttoman History: An Introduction to the Sources, represents a summation of that scholarship, an introduction to the state-of-the-art in Ottoman history, or as the author herself describes it, a sharing of her own fascination with the field. In a compelling and lucid exploration of the ways that primary and secondary sources can be used to interpret history, the author reaches out to students and researchers in the field and in related disciplines to help familiarise them with these documents. By considering both archival and narrative sources, she explains to what ends they were prepared, encouraging her readers to adopt a critical approach to their findings, and disabusing them of the notion that everything recorded in official documents is necessarily accurate or even true. Her critique of the handbook treatments of Ottoman history, quite often the sources students rely on most frequently during their undergraduate years, provides insights into the broader historical context. While the book is essentially a guide to a rich and complex discipline for those about to embark upon their research, the experienced Ottomanist can expect to find much that is new and provocative in this candid and sophisticated interpretation of the field.

S U R A I Y A F A R O Q H I is Professor of Ottoman Studies in the Department of Near Eastern Studies at Ludwig Maximilians Universitat in Munich. Her many publications include Pilgrims and Sultans (1994) and Kultur and Alltag im Osmanischen Reich (1995). She is a contributor to Halil Inalcik (with Donald Quataert), An Economic and Social History of theOttoman Empire, 13001914 (1994).

MMMM

Approaching

Ottoman

History

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE SOURCES

SURAIYA FAROQHI

Ludwig Maximilians Unversitat

The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom

The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK

40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcn 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain

Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org

Suraiya Faroqhi 2004

First published in printed format 1999

ISBN 0-511-03354-0 eBook (Adobe Reader)

ISBN 0-521-66168-4 hardback

ISBN 0-521-66648-1 paperback

To Tulay Artan and Halil Berktay, pursuing a common project of knowledge...

MMMM

C O N T E N T S

List of illustrations

viii

Acknowledgements

ix

Introduction

Entering the field

Locating Ottoman sources

Rural life as reflected in archival sources: selected examples 82

European sources on Ottoman history: the travellers 110

On the rules of writing (and reading) Ottoman

historical works

Perceptions of empire: viewing the Ottoman Empire through general histories

Conclusion

References

Index

I L L U S T R A T I O N S

Mevlevi dervishes. Roman Oberhummer and Heinrich

Zimmerer, Durch Syrien und Kleinasien, Reiseschilderungen undStudien (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, Ernst Vohsen, 1899), p. 259. 35

Waterwheel on the Kzlrmak, near C

okgoz bridge.

Oberhummer and Zimmerer, Durch Syrien und Kleinasien,Reiseschilderungen und Studien.

Windmills in Karnabad. F. Kantiz, Donaubulgarien und derBalkan, historisch-geographische Reisestudien aus den Jahren18601878, 3 vols. (Leipzig: Hermann Fries, 1875, 1877, 1879), II, p.374.

A Bulgarian peasant dwelling near Sucundol. Kanitz, Donaubulgarien, II, p. 84.

Turkish village house near Dzumali. Kanitz, Donaubulgarien, III, p. 41.

A Bulgarian peasant family winnowing (Ogost). Kanitz, Donaubulgarien, II, p. 374.

Manufacturing attar of roses. Kanitz, Donaubulgarien, II, p.123. 93

Khan and mosque in Razgrad. Kanitz, Donaubulgarien, III, p. 289.

Salonica, around 1900. Hugo Grothe, Auf turkischer Erde,Reisebilder und Studien (Berlin: Allgemeiner Verein fur Deutsche Litteratur, 1903), opposite p. 316.

The Suleymaniye, one of Sinans major works. Basile Kargopulo, late nineteenth century (IRSICA, Istanbul) 165

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S

Every scholar accumulates debts to his/her colleagues. This applies more specially to the present book, which is so largely dependent upon secondary literature. I am grateful to my friends and colleagues Marigold Acland, Virginia Aksan, Arzu Batmaz, Halil Berktay, Palmira Brummett, Eleni Gara, Erica Greber, Huricihan Islamoglu, Barbara Kellner-Heinkele, Markus Koller, Sabine Prator, Donald Quataert, Richard Saumarez Smith and Maria Todorova for the time they have taken to improve the finished product. Some of them have read chapters and commented on them, others have provided bibliographical references and much appreciated moral support. Special thanks are due to Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, who allowed me to reproduce the photograph of the Suleymaniye by B. Kargopulo, from the IRSICA collection. The four anonymous readers of Cambridge University Press have caused much soul-searching, which hopefully has improved the quality of the final product. Special thanks are due to Christoph Neumann, who not only read the whole manuscript but even put up with different drafts, and to Christl Catanzaro, whose attention, patience and skill with the computer made life a great deal easier than it would otherwise have been.

If I had been able to follow the guidance so generously given to me, this book would have been much closer to perfection. As things stand, it would be churlish in the extreme to make my friends responsible for the many imperfections which doubtlessly remain.

N O T E O N T R A N S L I T E R A T I O N

Modern Turkish spelling has been used whenever the place, institution or person in question belonged to the Ottoman realm or pre-Ottoman Anatolia, albeit in a marginal way. Only when dealing with Arab or Iranian contexts has the EIs transliteration been adopted; this concerns primarily

x

the names of modern archives and sections of archives. The Turkish letter (I) has been retained, except in personal names and geographic terms occurring in isolation, (thus: Inalcik, Izmir). The titles of journals contain the (I) where appropriate.

I N T R O D U C T I O N

In this book I hope to share with my readers the fascination with Ottoman sources, both archival and literary in the wider sense of the word, which have become accessible in growing numbers during the last decade or so.

The cataloguing of the Prime Ministers Archives in Istanbul advances rapidly, and various instructive library catalogues have appeared, both in Turkey and abroad. On the basis of this source material it has become possible to question, thoroughly revise, and at times totally abandon, the conventional images of Ottoman history which populated the secondary literature as little as thirty years ago. We no longer regard Ottoman officials as incapable of appreciating the complexities of urban economies, nor do we assume that Ottoman peasants lived merely by bartering essential services and without contact to the money economy. We have come to realise that European trade in the Ottoman Empire, while not insignificant both from an economic and a political point of view, was yet dwarfed by interregional and local commerce, to say nothing of the importation of spices, drugs and fine cottons from India.

Next page