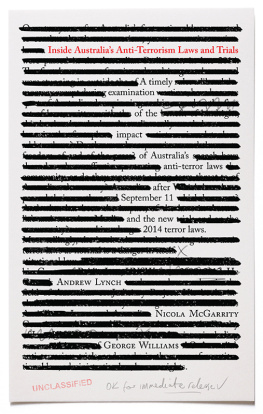

Copyright 2021 by Fernanda Pirie

Cover image ROMAOSLO via Getty Images

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Basic Books

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.basicbooks.com

First Edition: November 2021

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942287

ISBNs: 9781541617940 (hardcover), 9781541617957 (ebook)

E3-20210929-JV-NF-ORI

I n 1497 the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and into the Indian Ocean. He was on a mission to open up a sea passage to the rich eastern trading networks. His journey also opened European eyes to the rich and sophisticated world of Asia, with its extensive commercial and technological developments, complex governing structures, and laws. The Portuguese docked at Calicut, on the west coast of India, where grains, sugar, spices, coffee, textiles, metals, and horses were loaded and unloaded every day on their way to and from the Spice Islands, the Indian plains, and ports in East Africa and the Arabian Gulf. Eager to participate in this trade, da Gama visited the court of the local ruler. The Zamorin was none too impressed by his gifts and sent the European delegation packing. But the Portuguese persisted, and after further missions and threats of violence, they established trading posts on the Indian coast.

The merchants and adventurers who followed da Gama were impressed by the goods brought by Chinese traders, dazzled by the luxury and sophistication of the Muslim courts at Isfahan and Delhi, and intrigued by reports of the ancient Asian laws. In their distant capital at Beijing, Chinese rulers maintained a legal system that dated back to the third century bce . The Zamorin of Calicut, like other Hindu rulers, took advice from religious scholars, brahmins, who consulted the Dharmashastras. These centuries-old legal texts had their origins in the philosophical and ritual traditions of Indias Vedic period. Muslim legal experts referred to an extensive textual jurisprudence based on Muhammads revelations in the seventh century ce . In the courts of the sultans, well-trained judges dispensed justice, while scholars issued legal opinions and jurists conducted esoteric debates over ancient legal texts. The Europeans had nothing to compare in legal sophistication. Their own laws were still little more than heterogeneous collections of local customs and courts interspersed with the remnants of Roman jurisprudence.

By the early eighteenth century ce , everything had begun to change. The Qing had established a powerful new dynasty in China, the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan had built the Taj Mahal and extended a network of roads throughout India, and the Ottomans had threatened Vienna. But the Asian regimes were already faltering. The French legal philosopher Montesquieu still spoke with admiration of Chinas sophisticated and stable legal system, but he also condemned it as despotic. Enlightenment philosophers had persuaded European rulers that their political systems followed the most rational principles, while their laws promoted superior regimes of private property. And, as their industrial and military achievements outstripped those of Asia, European rulers became convinced that their political, educational, and legal systems were the best in the world. The intricate scholarship of the Muslim jurists, the learning of the Hindu brahmins, and the elaborate codes of Chinese law were, to their minds, the irrational and outdated institutions of a degenerate Orient.

The national legal systems now found throughout the world are almost all modeled on those developed by European nations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. During two hundred years of colonial rule, they exported and imposed their laws throughout the world and promoted a new international order of clearly demarcated states. Today, the leaders who take their seats at the United Nations are expected to maintain their own systems of laws and courts, as well as upholding democracy, human rights, and the rule of law. But within the long history of human civilizations, the rise and dominance of the state and systems of national law form just the latest chapter. The Europeans displaced legal systems that were already ancient when da Gama arrived in India, and even the Romans were inspired by earlier precedents. There is nothing inevitable about the shape that most legal systems take around the world today.

Most laws throughout history were very different from those considered appropriate in a modern state. For a start, laws have not always recognized territorial boundaries. Often, they travelled with merchants or religious scholars to new lands, where they generally came to coexist with local customs and rules. What is more, law and religion have often not been distinct. Particularly within the Hindu, Jewish, and Islamic traditions, legal rules have shaded imperceptibly into moral and religious guidance. Many ancient, and even quite recent, laws also defy the apparently basic requirements of efficiency, authority, and efficacy. Historically, many judges ignored the laws of their rulers, and plenty of laws were never enforced. Yet, highly impractical rules, which could hardly have contributed to the smooth running of their societies, were carefully written out on expensive parchment or chipped onto stone slabs. Time and again, historians have puzzled over what ancient laws were intended to do. Sometimes they have seemed little more than attempts to copy an older or grander civilization. Yet the Chinese traders, Hindu kings, and Muslim sultans that da Gama encountered all respected the rules of ancient legal systems. Their laws were just the latest examples of a technique that had been taken up repeatedly since it first emerged over four thousand years ago.

The oldest laws were created in Mesopotamia, the fertile lands lying between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in what is now Iraq. In the third millennium bce , the king of Ur ordered his scribes to write out a code of laws on a clay tablet. It followed a bold statement about the justice he could promise his people. Several centuries later, warlike leaders in central China inscribed ideograms onto bamboo strips and bronze vessels, which set out long lists of crimes and punishments. Their successors adopted the same methods to impose discipline on the officials and people of their expanding empires. On the plains of the Ganges, meanwhile, Indian scholars were crafting ritual texts based on the ancient wisdom of the Vedas. By the early centuries of the common era, brahmins were inscribing Sanskrit characters onto palm leaves to create the Dharmashastras, the foundational texts of Hindu law. Their successors travelled throughout South Asia, persuading rulers such as the Zamorin of Calicut to follow their rituals and adopt the Dharmashastras as codes of law. They were seeking to guide a body of religious adherents along a moral path.