Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

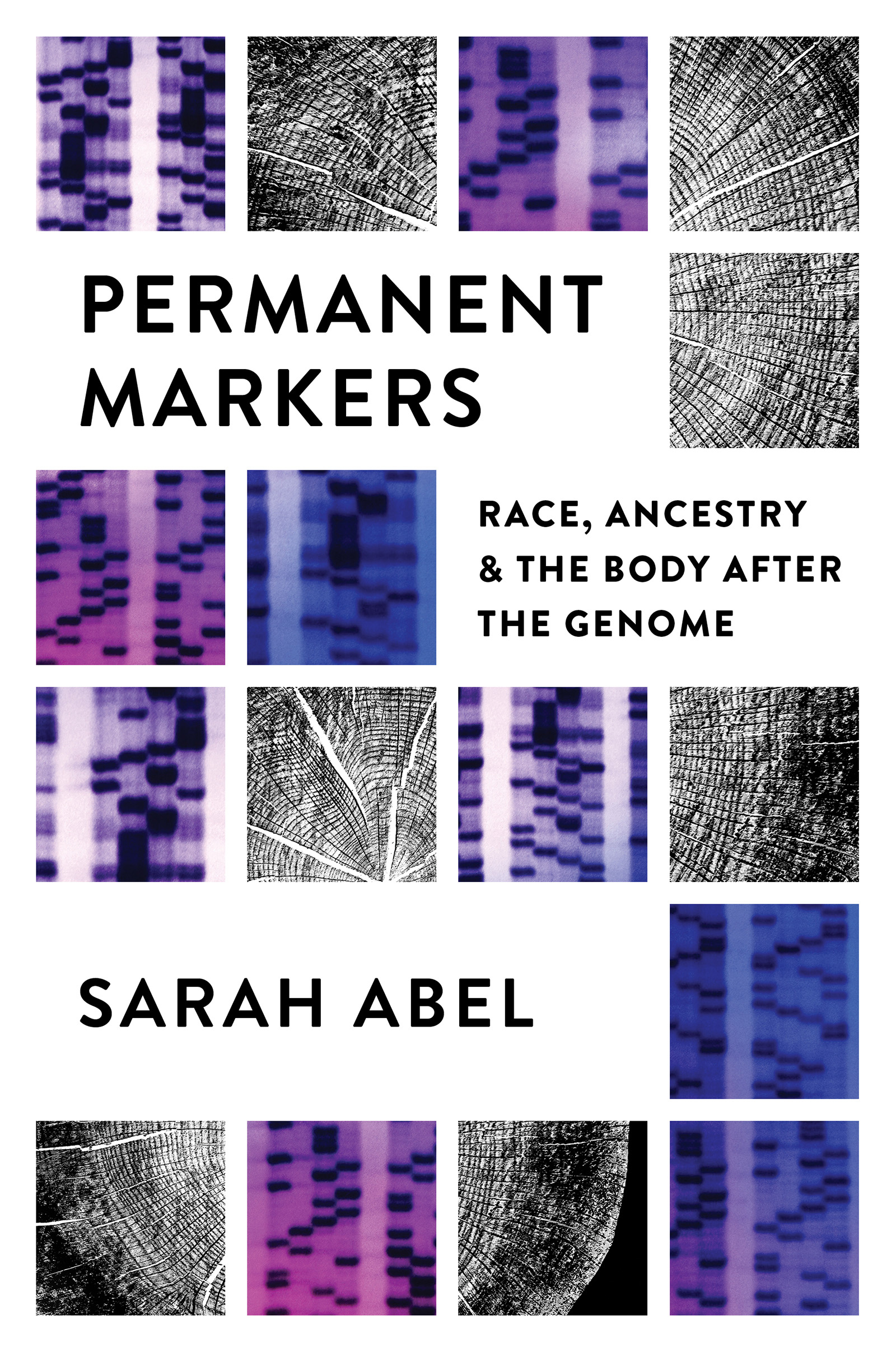

Permanent Markers

Permanent Markers

Race, Ancestry, and the Body after the Genome

SARAH ABEL

The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

This book was published with the assistance of the Lilian R. Furst Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2021 Sarah Abel

All rights reserved

Set in Charis by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Abel, Sarah (Cultural anthropologist), author.

Title: Permanent markers : race, ancestry, and the body after the genome / Sarah Abel.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021046312| ISBN 9781469665146 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469665153 (paperback ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469665160 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Genetic genealogyUnited States. | Genetic genealogyBrazil. | DNAAnalysisSocial aspects. | GenomicsSocial aspects. | Human geneticsSocial aspects. | Identity (Psychology) | Biotechnology industriesSocial aspects. | United StatesRace relationsHistory. | BrazilRace relationsHistory.

Classification: LCC CS21.3 .A24 2021 | DDC 929.1072 23/eng/20211dc14

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021046312

Cover illustration: X-ray of wood texture Shutterstock.com/captureandcompose; colored DNA sequencing autoradiograph by Michele Studer, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0), courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

Contents

- The World in Our DNA

- Historically Modified Organisms

Figures

Note on Language

Throughout this book, I employ various familiar anthropological terms and concepts that, in the context of the burgeoning world of DNA ancestry testing, are fast acquiring additional meanings and usages. In the interests of clarity, I have tried to reserve the use of inverted commas for new or potentially ambiguous uses of concepts. As I explore throughout the text, the terms race and ethnicity are contested categories that can take on very distinct meanings in different scientific disciplines and cultural contexts. Where they appear without inverted commas, they should usually be interpreted (unless signaled otherwise) as shorthand for the concept of race/ethnicity. Conversely, I use quotation marks to signal when they are used to convey an idea of concrete biological essences (human races, genetic ethnicities, racial mixture). The word color appears in quotation marks when it refers to the Brazilian concept cor (meaning an ensemble of racialized physical traits typically used as a basis for subjective evaluations about a persons ancestry, social standing, attractiveness, etc.). Throughout the book, citations of Brazilian interviewees and authors appear in my own English translation; in some cases, however, Portuguese words and phrases appear in italics, either to signal that no direct equivalent exists in English or to retain a particular nuance found in the original language. With regard to the various categories (racial, ethnic, genetic) that appear throughout my work, I have generally retained the original labels and nomenclatures used by DNA testing companies, scientists, and other social actors. One exception is my decision to capitalize the racial labels Black and White in the body of the text (original typographies are maintained in citations), to underline that these terms are not merely adjectives denoting skin color but sociopolitical categories with specific histories and local meanings.

Permanent Markers

Introduction

The World in Our DNA

The camera focuses in on a young woman with a mass of curly hair. She is facing forward, her eyes downcast, gazing fixedly on something in her lap. Behind her, slightly out of focus, rows of people sit facing the camera, some leaning forward expectantly. The woman blinks, her forehead creases, her lips purse and tremble; she is holding back tears.

The image cuts to a young man already wiping a tear from his eye. He stares transfixed at a piece of paper, his mouth hanging open in awe.

Cut again, and now we see a woman whose face is suddenly transformed from a nonchalant grin to a mask of shock. An envelope lies open on the table in front of her. The scene cuts to a black screen, with the words: Would you dare to question who you really are?

These scenes began to appear on various social networking websites in June 2016. They were the product of a short film made by Danish travel company Momondo and the U.S. genetic testing company AncestryDNA. Titled The DNA Journey, it featured a group of sixty-seven people from around the world and all walks of life receiving the results of their personalized DNA ancestry tests. After discussing their own national or ethnic identity and laying bare their personal prejudices toward other nationalities, the participants were invariably shown laughing and shedding tears as their preconceptions were blown away by the diverse array of origins displayed in their DNA results. An Englishman who expressed a dislike for Germans grinned wryly as he discovered he had 5 percent German ancestry, while a Frenchwoman who was attributed zero percent French ancestry exclaimed that genetic tests should be made compulsory, because if people knew their heritage like that, who would be stupid enough to think of such a thing as a pure race? At its climax, the video showed two of the participants embracing joyfully, to the applause of the others, as they learned they were cousins. Imparting these genetic results, over and over again, were two White, bespectacled scientists whose air of benevolent authority seemed to sum up the power of genetics to reveal deep and awesome truths about human identity.

The film closed with a final uplifting message: You have more in common with the world than you think. An open world begins with an open mind. For many viewers, the film represented a ray of hope amid a rising tide of political nationalism and a growing refugee crisistopics that dominated global headlines that summer. It also epitomized a belief that the spread of genetic knowledge has the potential to eliminate prejudice and transform human relations for the better. But is combating xenophobia and racial oppression really as simple as taking a DNA test?

Self-Discovery through the Genome

This is a book about the relationships between bodies and identities, and the collision between a century of anthropological thought about race with the arrival of consumer genomics. It follows in the wake of a long-standing body of scholarship that has sought to separate out the influence of biology and culture on human identities. According to the orthodoxy established by the UNESCO Statements on Race in the 1950s, religion, nationality, language, and ethnic affiliation are all cultural constructs: fluid, mutable, and overlapping, and by no means determined by, or even fundamentally linked to, a persons physical features or genetic inheritance. While patterns of genetic variation have been found to reflect underlying biological structuresthe relics of the migrations of early modern humans into different world regionsfundamentally, all living humans are understood to be members of one extended family.