Joseph Allchin - Many Rivers, One Sea

Here you can read online Joseph Allchin - Many Rivers, One Sea full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Oxford University Press USA, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

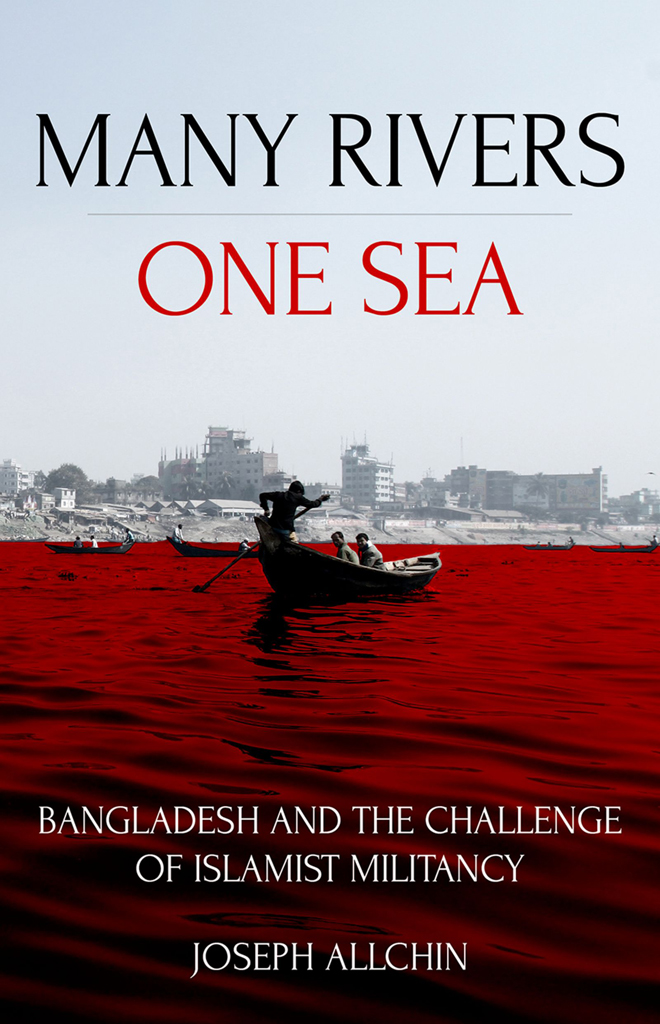

- Book:Many Rivers, One Sea

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press USA

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Many Rivers, One Sea: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Many Rivers, One Sea" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Many Rivers, One Sea — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Many Rivers, One Sea" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Islamist Militancy

First published in the United Kingdom in 2019 by

C. Hurst & Co. (Publishers) Ltd.,

41 Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3PL

Joseph Allchin, 2019

All rights reserved.

Printed in India

Distributed in the United States, Canada and Latin America by Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

The right of Joseph Allchin to be identified as the author of this publication is asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

A Cataloguing-in-Publication data record for this book is available from the British Library.

EISBN: 9781787382701

www.hurstpublishers.com

This book was conceived in the rubble of a hostage crisis. The crisis shook Bangladesh and drew international attention to the country, for all the wrong reasons. But it also happened at a strange time globally. I was not far away in Dhaka when the attack by five young men on the Holey Artisan Bakery took place on the evening of 1 July 2016. I had left the UK for Bangladesh only a few days before, on 24 June, the morning after that country, my country of birth, was convulsed by its shock vote to leave the European Union, in the so-called Brexit referendum. In hindsight, the mornings of 24 June and 2 July 2016 were strangely similar. When morning light returned to the corpse of a body politic, it seemed to reveal a hitherto less-than-well-understood angerseemingly populist and organic, but at the same time, at least in certain ways, deeply intertwined with the machinations of sections of the political classes. The relationship between these two types of force, the popular and the political, forms the basis of the analysis in this book.

I started out trying simply to tell the story of a sequence of events in Bangladesh that spawned the modern phenomenon of militancy in the country. In doing so, through snapshots of, on occasion, disparate times, events and actors, I also delve into how historical movements and ideologies forged anxieties and the grounds on which militancy has arisen. Extremism and subsequent terrorism or militancy are intensely social activities. They cannot simply be understood through grand political or historical acts or formal organisations. This is particularly the case in Bangladesh, where politics and mobilisation are characterised by great informality, in a society comparatively un-governed by formal institutions. This informality is vital to understanding Bangladesha young country, where through the vicissitudes of recent centuries the land and people have so often been viewed as subordinate or peripheral. Here, societal structure, institutions and behaviours seem to be deeply traditional and ingrained, but are in reality dynamic, contested and fluctuating. Bangladesh, for example, adheres little to traditional social constructs such as caste. With centuries of foreign domination, institutions of sovereign statehood are also newer and less rigid. As a result, they are less durable and effective.

In many analyses of contemporary Bangladesh, this informality is most often seen as a challengeat bestand otherwise as a crippling Achilles heel. But the view of this phenomenon as necessarily negative is mistaken. It could be argued that it has helped encourage some of the improvements that Bangladesh has made in human developmentthe country did well in meeting most of the UN Millennium Development Goals, for instance, through greater inclusion of women in the economy and womens empowerment more broadly. While this book does not set out to examine these issues per se, it is also worth noting that these characteristics of informality and dynamism make Bangladesh important and worthy of greater consideration from scholars and the global public.

The phenomenon of modern-day extremism, whether with Islamic characteristics or not, is imbued with the fragmented informality that globalisation, increased connectivity and the post-Cold War global political economy have created. Thus, while most analyses of development and politics would suggest that Bangladesh is converging or attempting to converge with the world, through the endeavours of the state and attendant stakeholders, it could be argued that the world is in fact converging with Bangladesh. In a world of intense economic competition and growing ecological fears, small states are often felt to be failing their citizens. Bangladeshs informality means that it has lived through and faced many of the worlds emerging challenges.

Bangladesh is increasingly described as emerging, and it is in a sense doing so from unimaginable tribulations in recent centuriesfrom colonialism to famines to genocides and more. Once seen as being at the wrong end of the Gangetic plain, Bangladesh now sits at a fulcrum point between the worlds two most populous nationsIndia and Chinain the middle of a region that is ever growing in importance. It could be argued that young people in Bangladesh are living a more quintessentially twenty-first-century existence than any group of people anywhere else, emerging rapidly from traditional agrarian existences into more interconnected and more deeply competitive, yet informal and crowded, urban lives. Their reality will come to be the norm for people all over the world. While the worlds attention is drawn to the denizens of cities such as New York or Singapore, the reality of our collective future as a species is far more tangibly exemplified by the young people of Gazipur or Mohammadpur. The anxieties, cultures and movements that are thrown up by the paradigms of those communities will affect far more people than those of the aforementioned bastions of wealth and magnets of global attention.

It is no doubt a challenge writing a book such as this as an outsiderneither a Bangladeshi citizen, nor a Muslim, nor even a scholar of that great world religion. Islam has so shaped the region, governed its peoples behaviours, and given faith and guidance to multitudes through hard and less hard times. Of this I was very aware when writing, researching and thinking about this book. But here and in other writing, I hope that the perspective of a relative outsider, invested only as a passive observer to tell stories of political significance, can add something to telling the story of the region. However, as the great thinker Edward Said observed in the introduction to his seminal work Orientalism:

No one has ever devised a method for detaching the scholar from the circumstances of life These continue to bear on what he does professionally, even though naturally enough his research and its fruits do attempt to reach a level of relative freedom from the inhibitions and the restrictions of brute, everyday reality.

Indeed, detaching oneself from the brute, everyday reality of Bangladeshi politics can be particularly difficult. The countrys informality creates what is commonly referred to as a culture of zero-sum politics. It is deeply confrontational, and, by necessity and definition, one in which a winner-takes-all paradigm must prevail. It can thus be hard to freely analyse and engage with multiple perspectives on issues that arise in this book: power, identity, religion, state and society. It is difficult to escape from the convenient labels that are used to rapidly ascribe friend or foe in the fraught debates that rage on social media, on the street, in offices of state, and beyond. Veracity can often be the victim, from official government denials of fact to tropes that circulate on social media.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Many Rivers, One Sea»

Look at similar books to Many Rivers, One Sea. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Many Rivers, One Sea and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.