The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

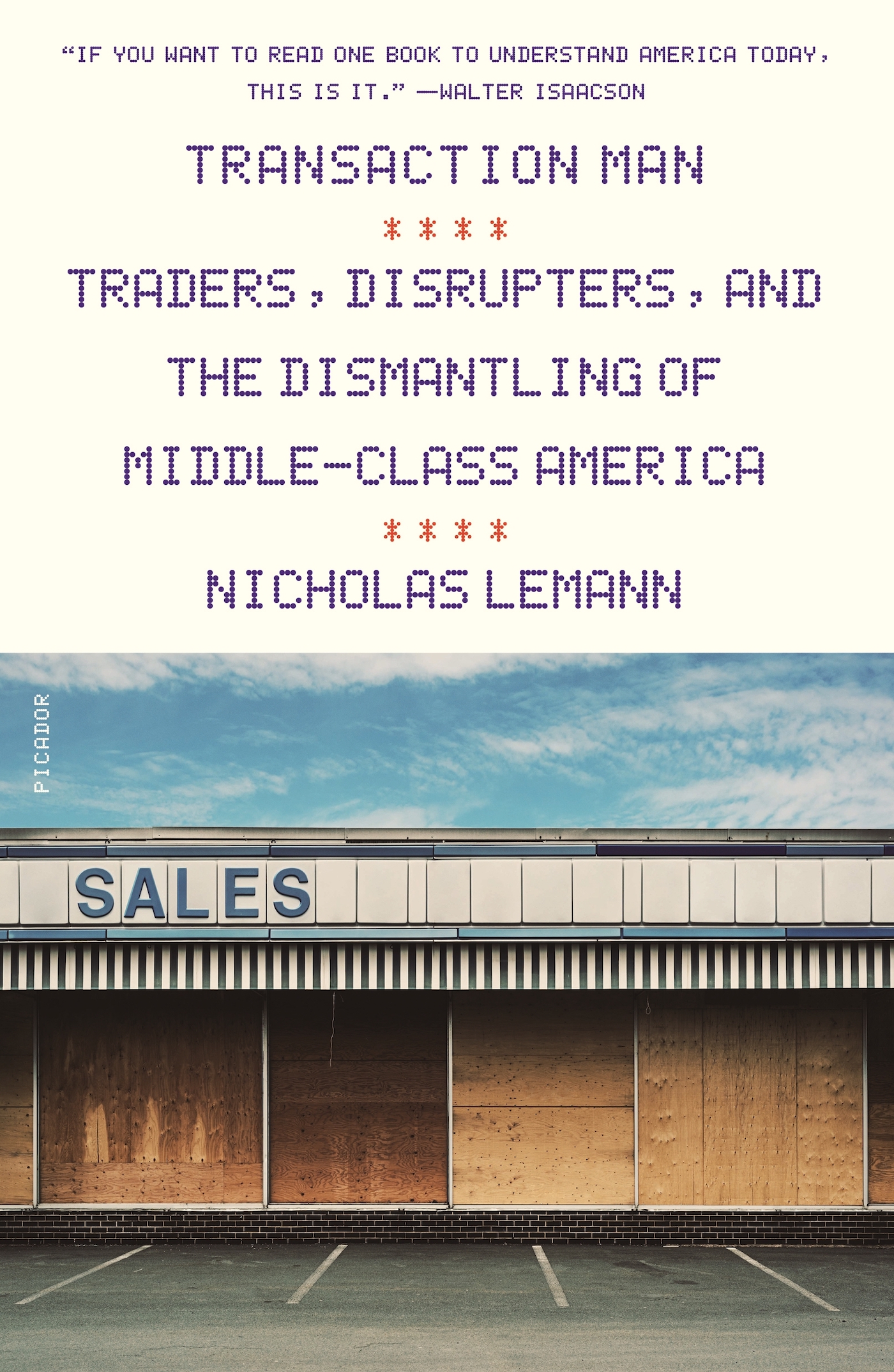

There are moments in history when everything seems calm, when there isnt obvious, bitter contention about big questions. It takes some effort now to remember that the dawn of the new millennium was like that, at least to the minds of fortunate people in the United States. As the portentous date approached, it was possible to believe that a happy age had begun. The great struggle over the Soviet Unions ambitions during the last half of the twentieth century had ended. There was no evident argument regarding the rightness of capitalism as the dominant economic system and democracy as the dominant political system; surely the places where they did not prevail would soon be brought into their warm embrace. The world was peaceful and prosperous, relatively speaking. American influence in every aspect of life, from banking and technology to movies and sneakers, had spread everywhere. The miraculous advent of the Internet was making instantaneous global communication and commerce possible.

Everything seemed calm and settledand then, boom, it wasnt. The two decades since the millennium have brought a series of unpleasant surprises wildly at odds with the way things seemed to be going. First came the September 11 attacks and the endless wars that followed from them; then the sudden collapse of the supposedly invulnerable financial system; then, substantially as a result of that collapse, a similarly unexpected disintegration of political consensus, leading to the rise to power of right-wing nativist politicians in the United States and many other places in the world. It wasnt long before every item on the optimists old checklist, including the most important onesconfidence in the future of capitalism and democracyhad begun to seem misguided.

Economics and politics usually operate together as a societys main organizing principles. Somehow the connection between them broke. Dramatic events made its brokenness evident, but those events were effects, not causes. To find out what happened requires looking under the surface. Headline-making news is easy to see; the rules that shape our everyday lives are not. Obviously they changed, a great deal. When did that happen, and who did it, and why? As a result, who has more power now and who has less? Whose interests are taken care of and whose are ignored? What can you do to provide yourself with some security and hope, and what would be fruitless? These are the kinds of questions people often talk about at seminars and conferencesusually people who are not directly on the receiving end of what happened. To understand the urgency of these questions, it may help to meet some of the people for whom they are not interesting and abstract, but concrete and terrifying.

On May 15, 2009, FedEx dropped off an ominously slender package from General Motors at the parts department at DAndrea Buick, on the South Side of Chicago. Okay, maybe the FedEx guy didnt know what was in the package, but it was typical that nobody thought to make sure it went to the main office. The parts department got the package to Nick DAndrea, the owner, a strutting bantam rooster with a broad chest, a head of curly white hair, and sharp eyes that moved around, taking everything in. He tore it open and found that he was out of business.

What was happening? The world was falling apart. It had been falling apart gradually for quite a while, from Nick DAndreas point of view, and now it was falling apart quickly. General Motors, the Gibraltar of the American economy as far as Nick was concernedthe General!had gone bankrupt. It meant that the whole dense, built-up web of arrangements that gave some protection to a small one-store auto dealer like Nick was null and void. President Barack Obama had appointed a car czar, a guy from Wall Street who didnt know the car business, and he had decreed that in exchange for its $50 billion in government bailout money, GM, along with Chrysler, which was also bankrupt, would have to close more than a thousand dealerships all over the country. DAndrea Buick was one of them. The letter told Nick to sell his inventory and close his store in a month.

Nick had lived his whole life in Chicago. He thought he knew how life was supposed to work: it was far from perfect, but at least it was understandable. Showing loyalty, being straight with people, and maintaining connections was everything. If you did all that and something still went wrong, it meant that somebody somewhere didnt wish you well or had some kind of deal going that you were on the wrong side of. GM used to send a guy around to visit DAndrea Buick every so oftena good guy, who could see how well Nick was running the dealership. Then the Internet came along, and the visits were replaced by teleconferences. At one of the teleconferences it was announced that GM was going to start combining several brands into single dealerships; Buick was going to be put together with Pontiac and GMC trucks.

GM started putting heavy pressure on Nick to absorb a nearby Pontiac dealership that wasnt doing well. He resisted like hell, but in 2007 the company gave him an ultimatum: do this, or your business will be in jeopardy, because we control your supply of cars and, in the end, the franchise that lets you operate as a GM dealer. So Nick, whod been proud to operate a debt-free dealership, borrowed moneyfrom GMs credit company, GMACand bought out the Pontiac dealer. Then he had to get a floor plananother loan, also from GMto stock his dealership with new Pontiacs. And he had to renovate the building, using a GM-approved architect, again with money borrowed from GM. By the time he reopened, he was in debt to GM for close to a million dollars, with heavy monthly payments to meet, and he had mortgaged both the dealership and his house.

Nick started selling Pontiacs along with Buicks in August 2008. In September, the financial crisis hit. On the South Side of Chicago, everybody buys cars with borrowed moneybut suddenly you couldnt borrow, because the credit markets had frozen. The Pontiacs were just sitting there. Then, in October, Nick got a letter from GM saying that in a few months it was going to terminate Pontiac as a brand. (What had saved Buick? It was a status brand in China.) So he was fighting for his survival even before the termination letter arrived in May.

Nicks grandfather was an immigrant from a village in Southern Italy who had found work in Chicago as a pick-and-shovel guy, digging sewers and subway tunnels. His father was a maintenance electrician for Kodak. The family lived in an Italian neighborhood, went to church, sent its kids to Catholic schools, and served as foot soldiers in the mighty Chicago Democratic political machine. Experts can say what they want about the importance of civil society in neighborhoods like the one on the West Side of Chicago where Nick grew up, but that concept overcomplicates things: it was really just church (Catholic) and state (the machine) that had been the dominant forces in the lives of poor Italians for centuries. The police were Irish, and there was no love lost between them and the Italians, but as Nick liked to say, if you needed a cop, you called a cop and you got a cop. The local alderman was Vito Marzullo, a legendary, all-powerful Chicago politician. If you wanted something or if you had a problem, you went to your precinct captain and he went to Marzullo and made the case. Otherwise you kept your mouth shut. Your economic life was essentially an offshoot of your political life. Jobs, from the Chicago neighborhood perspective, came not from abstract concepts such as economic growth or innovation or entrepreneurship, but from Marzullo: either they were patronage jobs with the city or the county, or they were quasi-patronage jobs with large, stable corporate employers who knew it was a good idea to be on friendly terms with the machine. And on election day you repaid your debts by delivering votes for the Democratic Party.