Praise for

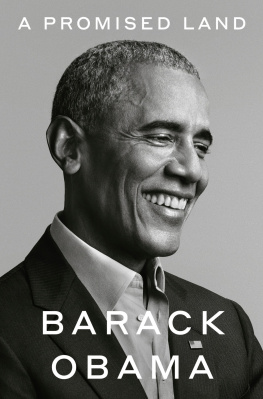

THE PROMISED LAND

Winner of the 1991 Los Angeles Times Book Award for History

Winner of the First Annual Southern Book Critics Circle Award, 1991

Winner of the 1991 Helen B. Bernstein Award for Excellence in Journalism

An absorbing chronicle of the past that shaped the present, The Promised Land is both gracefully written and heartfelt. Lemanns work has helped frame the national debate on some of the most vexing issues of the day.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Brilliant if we would understand the problemwhich is the first step toward fully wanting any programs to succeedThe Promised Land is, along with Taylor Branchs Parting the Waters, one of the two indispensable books.

Garry Wills, New York Review of Books

Nicholas Lemanns well-written, thoughtful, and controversial account of race, poverty and public policy in America will continue to provoke discussion. The Promised Land is must reading for anyone interested in the problems of urban migration and the way policy makers addressed them.

William Julius Wilson, University of Chicago

Indispensable The Promised Land is an important cornerstone in the effort to understand why so many travelers never reached the land of milk and honey.

Time

The Promised Land is a compelling and powerful book that should be read by anyone interested in the continuing history of racial oppression and conflict in the United States. Lemann successfully interweaves personal narratives of African-American migrants and their families with the discouraging story of politics and public policy in Chicago and Washington.

David Brion Davis, Yale University

Nicholas Lemann stirs ones conscience, and gets one wondering when the momentum of history will change once again and the promise of a less ironic meaning of his books title will finally be fulfilled.

The New York Times

The Promised Land is a fascinating and deeply moving book, a masterpiece of social anthropology. Lemanns account of the political history of the War on Poverty ranks with the very best contemporary history.

David Herbert Donald, Harvard University

A meticulous documentation of why some federal programs failed so miserably; why others have been perceived as failures even when they were not; and how the perceived success or failure of federal programs depends a lot on whether one is black or white this book is a valuable guide to an era that has shaped us as Americans, and about which little has been written in a comprehensive manner.

Patricia Williams, Boston Globe

An important book The Promised Land can be a first step on a journey toward an understanding of the relationship between the experience and perceptions of African-Americans, the impact of economic change on that experience and the formulation of public policy.

Chicago Tribune

NICHOLAS LEMANN

Nicholas Lemann was born and raised in New Orleans and has been a magazine writer since he was a teenager. He has worked at The Washington Monthly, Texas Monthly, and The Washington Post, and has been a national correspondent for The Atlantic. He is currently Dean of the School of Journalism at Columbia University.

Books by Nicholas Lemann

Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War

The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy

The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and

How It Changed America

The Fast Track

To my mother and father

Contents

CLARKSDALE

T HREE OR four miles south of the town of Clarksdale, Mississippi, there is a shambling little hog farm on the side of the highway. It sits right up next to the road, on cheap land, unkempt. A rutted dirt path leads back to a shack made of unpainted wood; over to the side is a makeshift wire fence enclosing the pen where the hogs live. Behind the fence, by the bank of a creek, under a droopy cottonwood tree, is an old rusted-out machine that appears to have found its final resting place. The vines have taken most of it over. It looks like a tractor from the 1930s with a very large metal basket mounted on top. Abandoned machinery is so common a sight in front of poor folks houses in the South that it is completely inconspicuous.

The old machine, now part of a hoary Southern set-piece, is actually important. It is the last tangible remnant of a great event in Clarksdale: the day of the first public demonstration of a working, production-ready model of the mechanical cotton picker, October 2, 1944. A crowd of people came out on that day to the Hopson plantation, just outside of town on Highway 49, to see eight machines pick a field of cotton.

Like the automobile, the cotton picker was not invented by one person in a blinding flash of inspiration. The real breakthrough in its development was building a machine that could be reliably mass-produced, not merely one that could pick cotton. For years, since 1927, International Harvester had been field-testing cotton-picking equipment at the Hopson place; the Hopsons were an old and prosperous planter family in Clarksdale, with a lot of acreage and a special interest in the technical side of farming. There were other experiments with mechanical cotton pickers going on all over the South. The best-known of the experimenters were two brothers named John and Mack Rust, who grew up poor and populist in Texas and spent the better part of four decades trying to develop a picker that they dreamed would be used to bring decent pay and working conditions to the cotton fields. The Rusts demonstrated one picker in 1931 and another, at an agricultural experiment station in Mississippi, in 1933; during the late 1930s and early 1940s they were field-testing their picker at a plantation outside Clarksdale, not far from the Hopson place. Their machines could pick cotton, but they couldnt be built on a factory assembly line. In 1942 the charter of the Rust Cotton Picker Company was revoked for nonpayment of taxes, and Mack Rust decamped for Arizona; the leadership in the development of the picker inexorably passed from a pair of idealistic self-employed tinkerers to a partnership between a big Northern corporation and a big Southern plantation, as the International Harvester team kept working on a machine that would be more sturdy and reliable than the Rusts. With the advent of World War II, the experiments at the Hopson plantation began to attract the intense interest of people in the cotton business. There were rumors that the machine was close to being perfected, finally. The price of cotton was high, because of the war, but hands to harvest it were short, also because of the war. Some planters had to leave their cotton to rot in the fields because there was nobody to pick it.

Howell Hopson, the head of the plantation, noted somewhat testily in a memorandum he wrote years later, Over a period of many months on end it was a rare day that visitors did not present themselves, more often than otherwise without prior announcement and unprepared for. They came individually, in small groups, in large groups, sometimes as organized delegations. Frequently they were found wandering around in the fields, on more than one occasion completely lost in outlying wooded areas. The county agricultural agent suggested to Hopson that he satisfy everyones curiosity in an orderly way by field-testing the picker before an audience. Hopson agreed, although, as his description of the event makes clear, not with enthusiasm: An estimated 2,500 to 3,000 people swarmed over the plantation on that one day. 800 to 1,000 automobiles leaving their tracks and scars throughout the property. It was always a matter of conjecture as to how the plantation managed to survive the onslaught. It is needless to say this was the last such voluntary occasion.