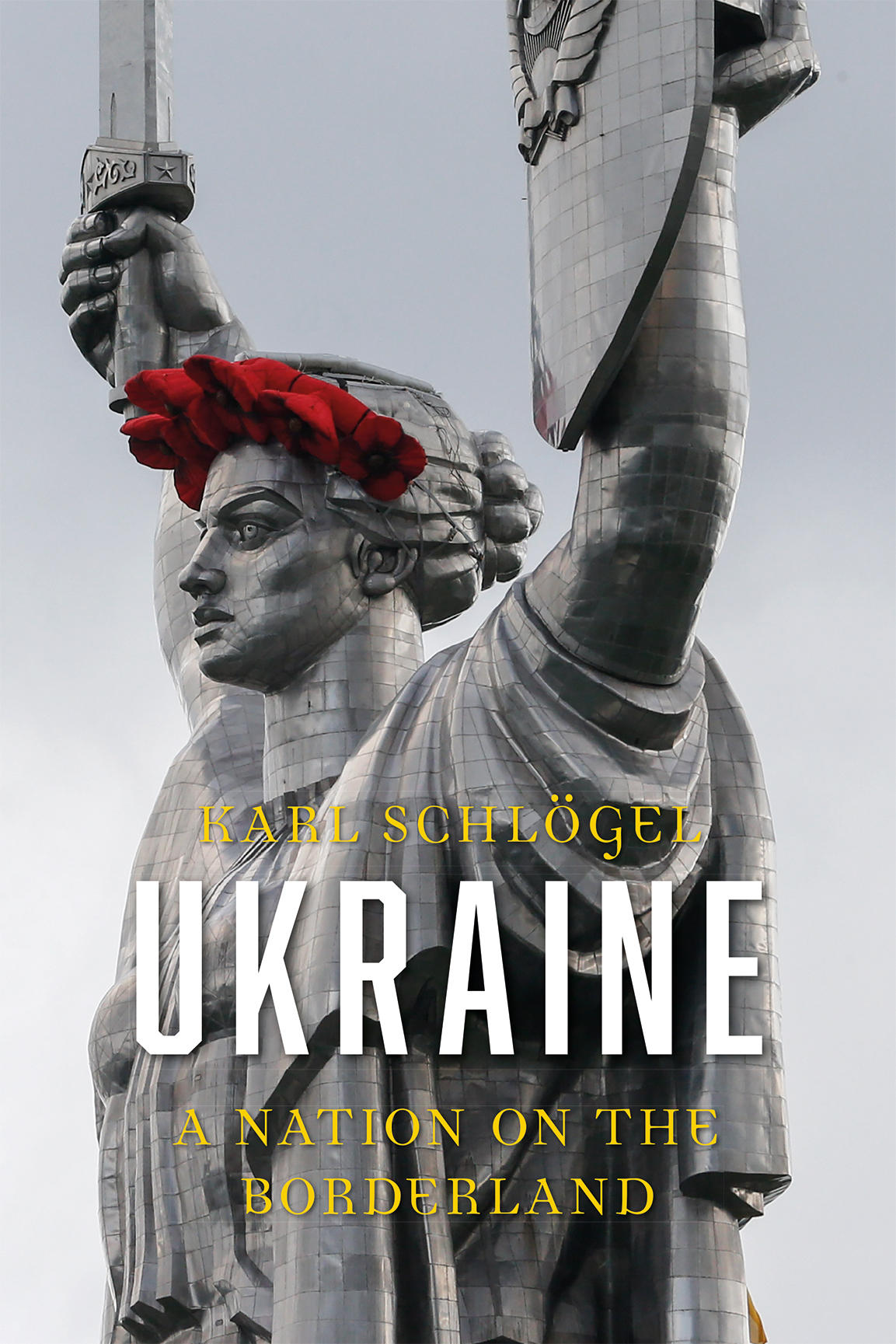

UKRAINE

UKRAINE

A NATION ON THE

BORDERLAND

KARL SCHLGEL

English translation by Gerrit Jackson

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

Unit 32, Waterside

4448 Wharf Road

London N1 7UX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published by Reaktion Books in 2018

English-language translation by Gerrit Jackson

Translation Reaktion Books 2018

Original title Entscheidung in Kiew. Ukrainische Lektionen

Carl Hanser Verlag Mnchen 2015

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut, which is funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International, Padstow, Cornwall

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781789140200

CONTENTS

UKRAINE, OR REMAPPING EUROPE: PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION

H ISTORY DOES NOT take breaks and rarely concludes with a happy ending. Still, the fall of the Wall and the Iron Curtain in 1989 inspired hopes, especially in Central Europe, that the decades-long Cold War dividing Europe into enemy blocs had been an extended state of exception now followed by a return to normal. Things turned out differently: Yugoslavias disintegration spawned new wars; the initial euphoria faded as nationalist and authoritarian regimes gained strength; corruption was endemic; Russia suffered from post-imperial phantom pains and proved ready to bully and attack neighbouring states.

Ukraine is where, in the twenty-first century, war has returned to Europe. Crimea, annexed in 2014, is still occupied by Putins troops; pro-Russian separatists have established a reign of terror in the Donbass. The territorial integrity of Europes second-largest country is violated day after day, and in this situation of perpetual aggression the implementation of urgently needed reforms has slowed to a crawl. All of this is playing out no more than a few hours by plane from Warsaw, Berlin or London. It sometimes seems that Europe has resigned itself to the permanent military incursion on its periphery the continent is overwhelmed as it is by the many concurrent crises: the Euro crisis, Greek crisis, Brexit, terrorism, the refugee crisis.

For the longest time, Ukraine as an independent nation with its own culture and history was non-existent on most Europeans mental maps. Many regarded it as a province and backyard of far larger entities Russia and, earlier, the Soviet Union. Ukraines political and cultural identity and the Ukrainian language were thought of as variants of their Russian counterparts. This incuriousness became untenable with the Revolution of Dignity that erupted in Kiev and other major cities in 2014, and especially with the undeclared war Putins Russia has waged against Ukraine. Europeans had to admit to themselves that they had only the haziest notions of the country and nation if they had any idea at all. So a portrait of Ukraine and its people, of its cities, towns and landscapes, of the manifold cultural and historical influences that moulded them, remains an acute desideratum. The essays on Ukrainian cities collected in this volume represent an attempt to apprehend this diversity in selected examples. They were written at different times between 1987 and 2015 and so also trace a shift of perspective: from a Russian-centric view in which Moscow was the unquestioned vantage point and Ukraine part of the periphery, to a keen appreciation of the ways in which Ukraine is an autonomous and distinctive nation. This shift did not come easily for a writer whose academic socialization took place in Moscow and Leningrad, now St Petersburg, but it has certainly been instructive.

In its particular interests and concerns, this book is recognizably the work of a German historian. Wherever the traveller goes in Ukraine, he encounters traces of German involvement in the countrys history, of positive contributions as well as atrocities. In the German perspective, Ukraine has rarely figured as more than a part of the Russian Empire (Little Russia), a colonial possession and Eastern European breadbasket, or a battle zone and occupied territory where millions became victims: Soviet prisoners of war, forced labourers, Jews. With Belarus, Ukraine was the main theatre of war and the single largest source of forced labourers from Eastern Europe; scattered across it are innumerable mass graves from the genocide against the Jews of Eastern Europe. It took Germans a long time to acknowledge that Russia was not the only target of the Third Reichs campaign of conquest and annihilation, and to accept the special responsibility for the fate of todays independent Ukraine this history implies.

The situation after the end of the Cold Wars division of the world and the demise of the Soviet Empire is reminiscent of the period after the First World War, with its numerous newly independent states and newly formed alliances, its shifting boundaries, minority conflicts and volatile domestic politics. The disaffection of ethnic and linguistic minorities was harnessed for revisionist foreign policy schemes; governments flouted the rules of peaceful dispute resolution. The experience of Munich 1938 exemplifies the illusion of appeasement Peace for our time in the face of a political strategy in which the annexation Europe and the West more generally have a hard time defining their place in a changed world. They are virtually unprepared for the new kinds of hybrid and asymmetrical warfare and slow to respond to the novel instruments of todays information war. They seem stymied by the intellectual challenges these forms of aggression pose, not to mention by the need to rethink the Wests military defence capabilities.

No end to the Ukraine crisis is in sight. The war rages on, and the danger that Ukraine will be destabilized remains very real. This is not just about Crimea or the Donbass: the larger question is whether Europe will close ranks and make a stand against the International that Putin is forging with allies from the far left to the far right. One prerequisite for effective and sustained support for Ukraine is a better understanding of its emergence as a nation and its natural and cultural diversity. The most obvious tokens of this complexity are the multiple names by which most places are known, each of which stands for a different historical period and political affiliation: Leopolis/Lww/Lemberg/ Lvov/Lviv, Kharkov/Kharkiv. More than in virtually any other European country, bilingualism and multilingualism are an unremarked-upon fact of daily life in Ukraine which is why, depending on the historical context, some places appear under different names in the essays collected in the following pages.

I am most pleased that the book, which has been published in Ukrainian, Russian and Spanish translations in addition to the German original, is now coming out in English. My gratitude goes to Michael R. Leaman, publisher at Reaktion Books, and to Gerrit Jackson, who has translated it with his usual diligence.

AUTHORS NOTE