ix

Preface

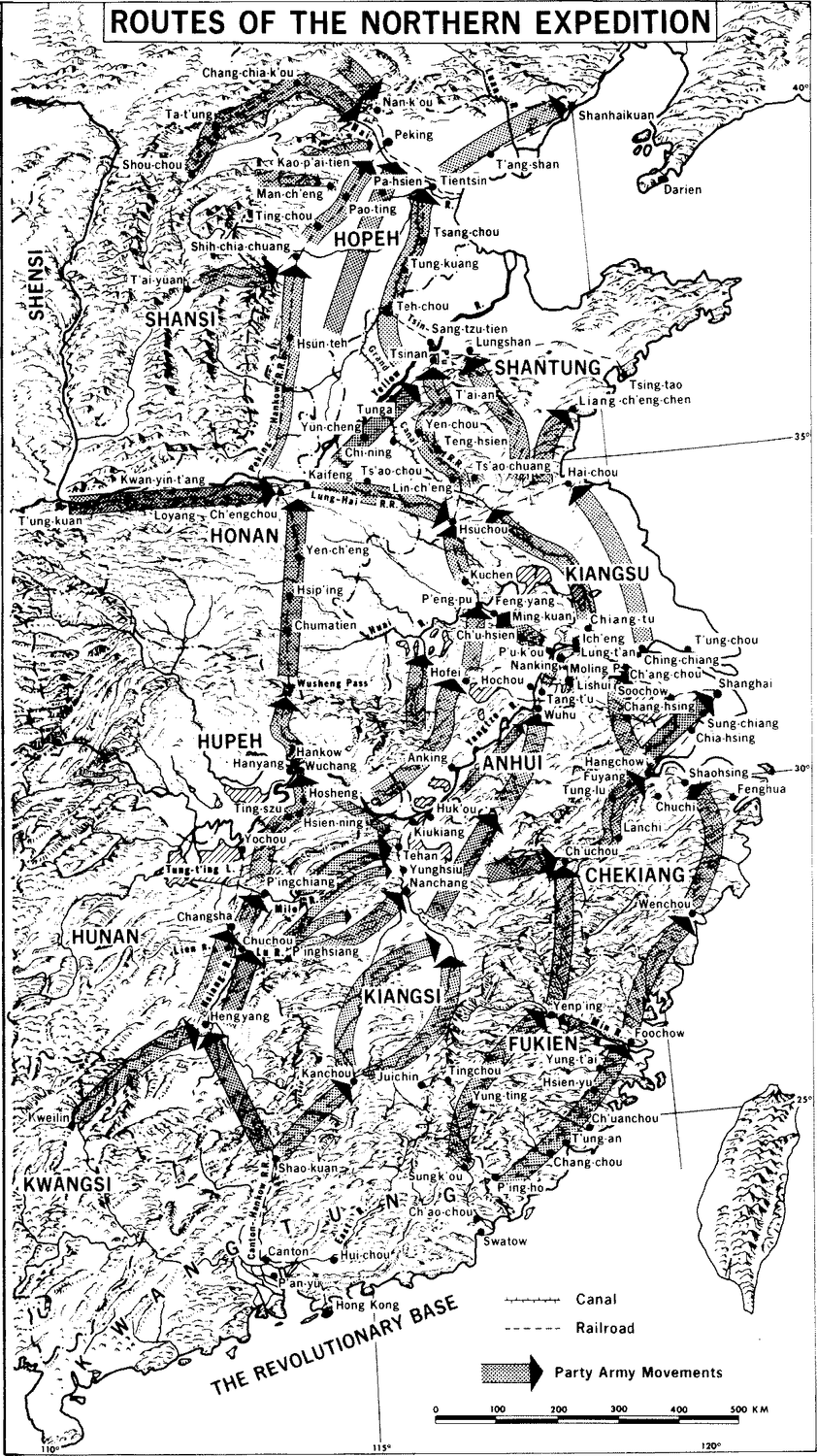

What was the Northern Expedition? Was it, as some acclaimed, the Great National Revolution? For some Marxists, the term national referred to a phase of necessary bourgeois development that would precede the more significant work of the Social Revolution. For Kuomintang members and others influenced by the West, nationhood was a state of community togetherness that strengthened the modern world powers. The goals of the Northern Expedition of 19261928 are as encompassing as was Chinese nationalism in the 1920s. The arguments favoring nationhood differed then widely according to individual levels of education, modernization, and politicization. It may be easier to describe what it was against than what nationalism was for. Those promoting the expedition and the national movement were opposed to the status quo. Dismal decades of defeat as the Ching regime fell apart had shattered the Chinese self-satisfaction. The failure of the revolutionaries after 1911 to reintegrate and reorder the Chinese state led to continuing disappointment and disillusionment. Both idealistic Chinese youth and their elders craved some improvement from the enervating disunity. The many military governors in their provinces marched their mercenaries and seemed more bent on grabbing from fellow Chinese than they were anxious over the greed of foreign imperialists. Chinas loss of face in the world community was sensed mainly by those most aware of the outside world. Keeping fresh the disgrace of Japans gains from Yuan Shih-kai, the nationalists who commemorated National Humiliation Day were not the peasants hoeing in the field. By the launching x of the expedition in 1926, the National Revolution was an inclusive multilevel movement.

In order to achieve national reunification, the Northern Expedition of necessity became a many splendored thing, gathering in as many dissident elements as possible. Judging the success or tragedy of such a union was left to a later period. The only demand shared by all the participants was for a new, more integrated political system for China, one that would replace the existing, defenseless, kaleidoscopic patchwork of warlord satrapies.

The young elite educated in modern ways who gathered in the treaty ports were among the most aware of nationalism. Although but a tiny part of Chinas millions, they were articulate, enthusiastic, and idealisticif rather inexperienced and impractical. But in the search for new alternatives, even this elite element lacked homogeneity, for some saw strength in national unity while others envisioned a social struggle among Chinese that would revitalize China. The symbol of their common desire for a stronger China and their divergence over means to that end was the United Front of the Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party from 1923 to 1927.

Also wanting a new chance for their plans were republicans, federalists, constitutionalists, and provincial autonomists. They, too, generally chafed under warlord rulers who were too strong for civilians to oust but too weak to resist the demands and bribes of foreign powers. Frustrated with his own impotence in Chinese politics, Sun Yat-sen had learned through bitter experience and forced exile that he would have to attract allies of all stripes. Although a symbol of nationalism for many, Sun allied himself with Kwangtung militarist Chen Chiung-ming and made overtures to regional overlords, such as Chang Tso-lin. Desperate to find means to pull Chinese together in a common cause, Sun had espoused provincial autonomy in federalism in 1921, but rejected them as the tide of nationalism swelled. In 1926 Chiang Kai-shek and other patrons of the military campaign resurrected them once again. With his experience in the outside world, Sun sought patronage from the United States, Great Britain, Japan, and finally from the Soviet Union. Sun then accepted Russias offer of aid free of imperialistic demands, but did not exclude the possibility of a rapprochement with the others.

The controversy as to whether Sun was a socialist, Communist, or a hybrid will be outside the scope of this study. Adherents of those ideological variants were gathered into the ranks of the national revolutionaries. The point to be introduced here is that the so-called National Revolution and its military phase, the Northern Expedition, cannot be labeled neatly as entirely nationalistic, socialistic, or opportunistic. Instead, the movement was a loose coalition of Chinese elites who were at least nationwide in their origins, if not nationalized according to Western specifications. They did share a righteous indignation over the treatment meted out to the disunited Chinese people by the foreign powers and their merchants. Only reunification could return to China the strength to determine her own destiny. Since it had become apparent that the armed forces of the warlords xi could only be overcome by military means, a new war would have to be waged to remove them as obstacles to reunification. Those militarists who would recognize the authority of the Kuomintang in national affairs could be eased into the movement as representing the interest of the people in their provinces.

The advantage of such an inclusive approach was its ability to quickly incorporate any who could contribute to the rapid reunification of China. Its weakness was to be the lack of a dynamic ideology that could keep the participants united and this led to misunderstanding and factionalism. Beyond the facade formed by these multifarious elites lay the vast masses of Chinese peasantry and the smaller clusterings of urban proletariats. How deeply did the desire for nationhood penetrate among them? Were the Chinese people as a whole responsive to the modern slogans of nationalism? The role of these peasants and workers received much publicity from Marxists and Trotskyites, which was what initially attracted my attention to the expedition. My evaluation of their role in the National Revolution is the most revisionistic or iconoclastic aspect of this study.

Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program.

Open Access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted.

Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non-commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copyrighted.