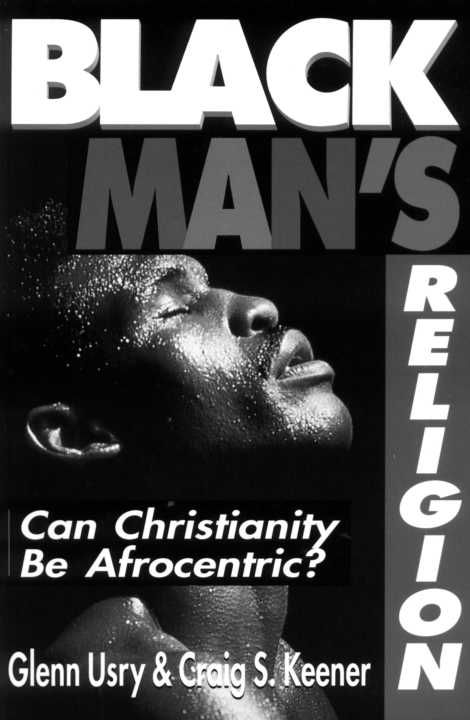

Glenn Usry - Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?

Here you can read online Glenn Usry - Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric? full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Glenn Usry: author's other books

Who wrote Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric? — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Glenn Usry & Craig S. Keener

The main title of this book is meant to be provocative more than precise. It responds to the historically inaccurate White idea (circulated today by some African-Americans as well) that Christianity is a "White man's religion." This is why our book is called Black Man's Religion-not, of course, to imply that non-Blacks are excluded, but to point out that biblical Christianity is a Black religion as much as a White one. Further, because the book addresses Black women as well as Black men, a more accurate title would be "Black People's Religion"-but choosing this title would have meant losing the deliberate contrast to the traditional phrase "White man's religion," which its users originally applied generically to White people. Although we intentionally address both men and women in our heritage, we retain the less accurate phrase solely to underline the contrast, because this book is a response to the charge that Christianity is a European and White American religion.

As most students of history recognize, the idea that Christianity originated as or remained primarily a European religion is unfounded. Christian history includes Asian, African and other representatives. In fact, we could never imagine that Christianity was ever strictly a European religion if we knew the facts of history-about the ancient church in East Africa, about the faith of our community's forebears on the plantations (though it was a Christianity quite different from that of the plantation owners) and so on. That is what this book is about: reminding African-American Christians of our firm place in history.

The authors of this book originally set out to write a brief manual on Afrocentrism and African-American history for use by New Generation Campus Ministries, an African-American Christian student movement. We especially wanted to respond to ill-informed objections against the Black church and selfconsciously African-American Christianity-objections raised both by White supremacists and by some Afrocentric ideologies that have opposed the Bible and biblical Christianity. The manual quickly grew in size and scope, and eventually, with NGM's blessing, we decided to make it available to a wider audience.

Although we have endeavored to make this book's answers as accurate as possible, we have also tried to make sure that it addresses the right questions. This is not a complete survey of Christians of color in history (a task both impossible in one volume and beyond our own training), nor do we address every issue raised by Afrocentric historians today. We choose to deal with a particular set of questions we are currently hearing among urban youth and college students. We also do not focus on the historic racism of many professed Christians; although the failure of many Christians to practice Jesus' teachings calls for serious comment, our work responds to those who associate Christianity more with White supremacy than with Jesus, so we are emphasizing the side of the evidence which our accusers have neglected. For the same reason, we have cited popular works of interest to the subject alongside scholarly works, and have focused less on scholarly theological works and more on works most relevant to the subject of the book. This is neither to denigrate the sources omitted nor to rank all works cited on the same level; it is to say that, as far as possible, we have focused on the purpose for which we wrote the book.'

To a great extent, the selection of information in this book thus reflects the original purpose for which the book was written: providing African-American Christian students with a deeper awareness of both their ethnic and their spiritual heritage, especially where those heritages coincide. One of the biggest issues is the objection (from members of the Nation of Islam and others) that Christianity is "a White man's religion"; second to that is the general accusation (held by White supremacists but not by the Nation of Islam) that everything noble in history is White. We respond to both, with most attention to the former objection. Too often we have found Christians unprepared to answer the objections that the Nation of Islam raises, despite the abundance of evidence that could answer these objections. But even though we respond to the Nation of Islam's critique of Christianity, we agree with them that African-Americans are right to affirm their African-American heritage.2 And as we respond to what we believe to be an inaccurate portrayal of our history, we do not intend any personal attack against those who hold contrary positions.3

We are in the process of completing a second volume responding to various specific objections to African-American Christianity, but we have devoted this entire first book to answering the inaccurate complaint that historically Christianity is not Black. This book thus grapples with two basic issues. The first, as noted above, locates precedents for our African-Christian heritage in history. The second issue is one we sometimes miss when discussing our heritage. If we are to identify with peoples in history, on what basis do we identify with them? We cannot very well write Afrocentric history (by which we mean history from an African-American perspective) unless we have decided the basis on which we as African-Americans actually identify with peoples in history. In actuality we identify with others on a number of grounds, and these various grounds will provide the different angles from which we can examine our place in history .4

To some extent we identify on the basis of common geographical origin (Africa), to some extent on the basis of common skin color (Black), to some extent on the basis of a common heritage of oppression and discrimination, and finally to some extent on the basis of a shared commitment to fight oppression and discrimination. Thus this book will address our heritage as African-American Christians in the following chapters: our African heritage (chapter two), race and U.S. history (chapter three), race and ancient Egyptian and Israelite history (chapter four), oppression, including medieval Arab and later Western slavery (chapter five) and justice through reconciliation (chapter six).

In all these respects Christianity still remains part of our heritage. If we identify with our heritage geographically, Christianity originated close to Africa and has maintained a strong presence in Africa from the beginning. If we identify with our heritage racially, Black Africans appear in prominent roles in the Bible (such as Jeremiah's rescuer and the first Gentile Christian), as well as in subsequent Christianity. If we identify with others who have been oppressed or who join with us in working for justice, the biblical gospel resonates most of all with the oppressed and summons its followers to work for justice. But of course ultimately we must choose Christianity not simply for these reasons but because we embrace its message of a God who embraced the need of all humanity in the cross.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?»

Look at similar books to Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric?. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Black Mans Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric? and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.