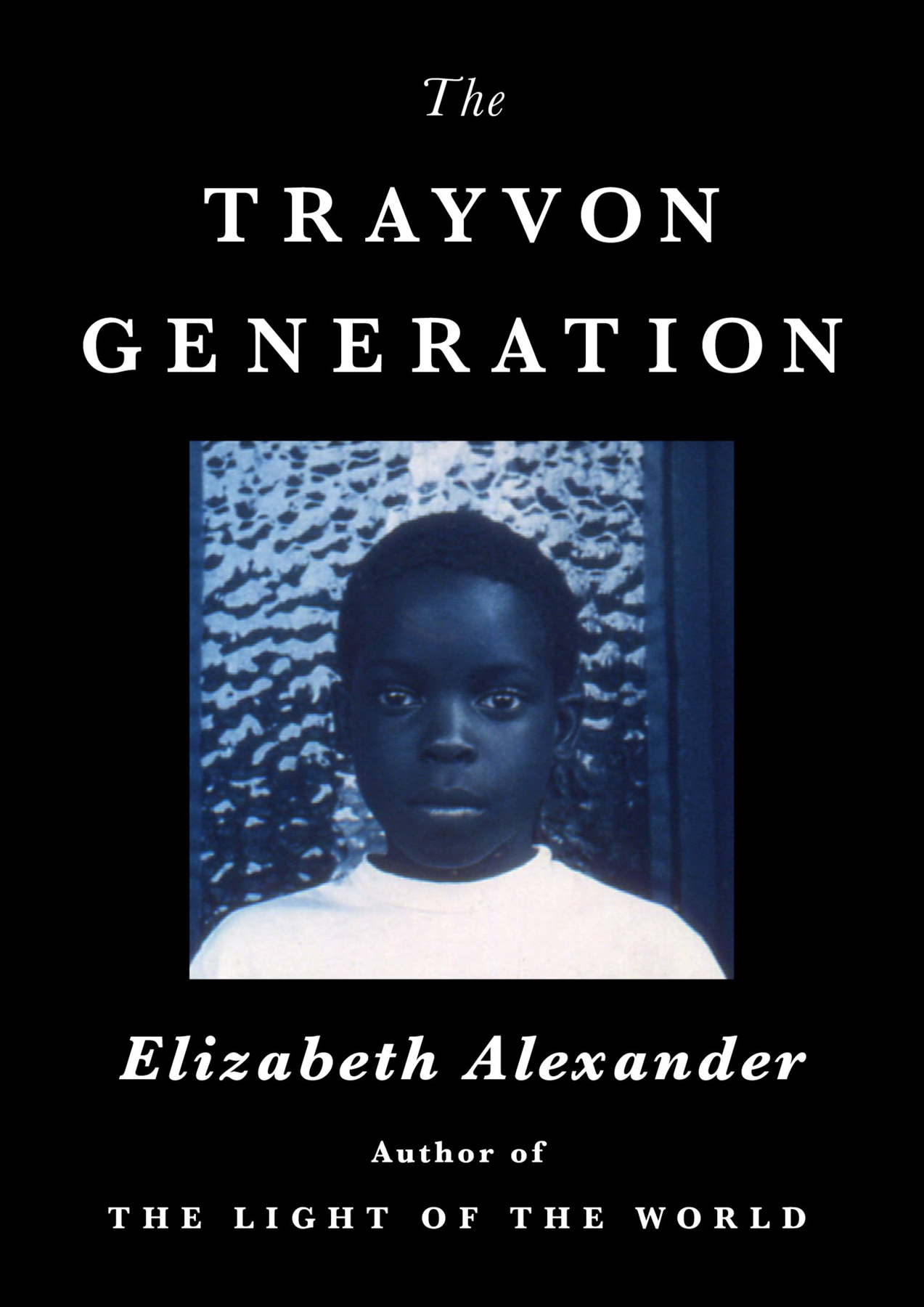

The problem of the twenty-first century remains the color line. Yes, we are mired in overlapping societal struggles and challenges. But white supremacy and its many manifestationssome of them sly and cloaked, some of them clear as a Confederate flag flown by marauders in the US Capitolhas been a fundamental problem for every generation in this country since Black people first came to this land. W. E. B. Du Boiss How does it feel to be a problem? is still the question implicitly and explicitly directed at Black people. The race work of the generations of my great-grandparents, my grandparents, my parents, and myself is the work of our childrens generation. I dont wring my hands that we didnt fix it; clearly it is unfixable by us alone. White supremacy is not the creation of Black people. I both lament and am enraged that this work is undone, and that our young people still have it to wrestle with.

Racial ideologies are insidious. They instruct in intricate, ambient teaching systems. The country is their classroom and everyone is in school, whether they choose to be or not.

Thus the color line is a fundamental, formative, constitutive American problem.

I was raised in troves of blackness: born in a Black metropolis, Harlem USA; reared in Chocolate City, Washington, D.C., which, in my childhood, was nearly three-quarters Black. From my family, I was given a sense of pride in our people and history, the need to understand myself as part of a larger whole and to be as helpful as I could to others, the familiar imperative to work twice as hard, and the responsibility to speak up when injustice was done.

When I found my professional path, it was as an educator, a scholar of Black culture, and an organizer of words, mostly poems. I wrote and thought and taught about the importance of witnessing; about the crucial functions of storytelling and history; about how the specter of violence hangs as constantly as the moon over Black people. I found knowledge and guidance in words, and possibilities in music, dance, and art, where I could go outside of words and access feeling and deep knowing. In Black history and culture, I encountered the full range of human experience, conundrum, perseverance, beauty, foible, and particularity. Here everything could be understood and I evangelized in my teaching and writing about this wellspring.

I believed that representation mattered, and that if more of us occupied spaces where justice-minded decisions could be made, power shared, and examples set, the race could move forward and, with that, all of society would strengthen itself and mend the corrosion of ignorance and racism.

Here is the thorny truth: while many sectors of society are now more integrated, violence and fear are unabated, and the war against Black people feels as if it is gearing up for another epic round.

This poem by Clint Smith gets to the perennialness and sorrow of race in America:

Your National Anthem

Today, a black man who was once a black boy

like you got down on one of his knees & laid

his helmet on the grass as this country sang

its ode to the promise it never kept

& the woman in the grocery store line in front

of us is on the phone & she is telling someone

on the other line that this black man who was

once a black boy like you should be grateful

we live in a country where people arent killed

for things like this you know she says, in some places

they would hang you for such a blatant act of disrespect

maybe he should go live there instead of here so he can

appreciate what he has & then she turns around

& sees you sitting in the grocery cart surrounded

by lettuce & yogurt & frozen chicken thighs

& you smile at her with your toothless gum smile

& she says that you are the cutest baby she has

ever seen & tells me how I must feel so lucky

to have such a beautiful baby boy & I thank her

for her kind words even though I should not

thank her because I know that you will not always

be a black boy but one day you may be a black man

& you may decide your country hasnt kept

its promise to you either & this woman or another

like her will forget that you were ever this boy & they

will make you into something else & tell you

to be grateful for what youve been given

The small word may is the devastation in this poem. In the scene at a supermarket, the precious Black boythe speakers sonis admired by a white woman who in the same breath decries the actions of a Black man asking better of his country, as we always have; she upends his belongingthat baby, in the words of his father, may grow up to be a black man. Not