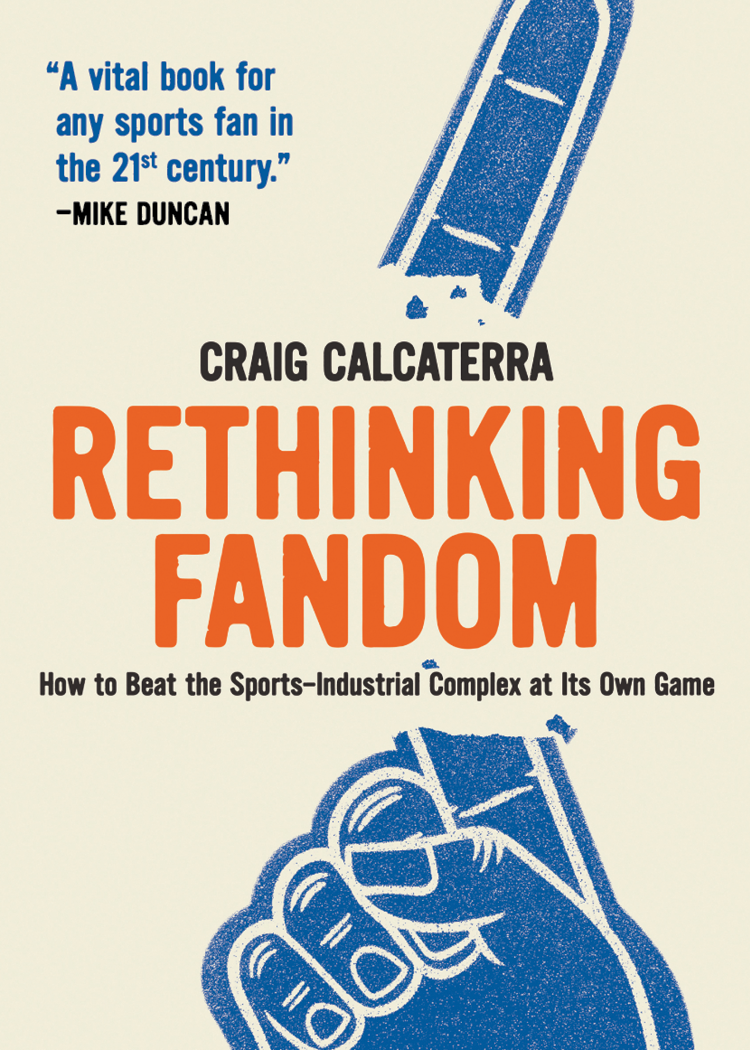

Copyright 2022 by Craig Calcaterra

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief

quotations in a book review.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition 2022

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-953368-24-9

Belt Publishing

5322 Fleet Avenue

Cleveland, Ohio 44105

www.beltpublishing.com

Cover art by David Wilson

Book design by Meredith Pangrace

For the people in the cheap seats who give far more than they get.

Contents

Y

Introduction

In early 2019, Geoff Baker, an investigative sports reporter for the Seattle Times whose work I admire, was given a new responsibility by the paper: he was assigned to cover the new National Hockey League expansion team in Seattle. The team did not yet have a name and certainly did not have any players. Indeed, it was still nearly 1,000 days before the team would even begin play. Despite that, there was obviously a lot to cover. News about the future teams ownership group. News about the massive ongoing renovation to Seattles arena, which would eventually be the teams home. News about the various rules and financial considerations that would directly impact the stocking of the teams roster and its competitive future in the NHL. Getting an expansion team going is pretty complicated, so it makes perfect sense that a major newspaper like the Times would dedicate someone to covering that beat.

But Bakers coverage also included something else: a weekly feature in which he responded to fan letters and emails. A great many fans had questions about those nuts-and-bolts issues on which Baker was reporting, of course, but there were often digressions by both the letter writer and Baker that revealed significant fan excitement around the new team. There was talk about the possibility of superfan groups like the Seattle Seahawks famous Twelth Man.

I dont follow hockey very closely, and I have little interest in Seattles sports, but whenever Id see Baker tweet out links to his mailbag, I was fascinated with the idea that a nameless, faceless team could have actual fans already, let alone budding superfans. By the time the team was finally dubbed the Seattle Kraken and given a logo and colors in the summer of 2020, there had already been a years worth of fan letters and emails crossing Bakers desk.

Upon even a little reflection, thats not terribly surprising. Fandombe it about sports, movies, comic books, TV shows, video games, or almost anything elseis about more than the basic activity that inspires it. Most sports fans dont spend a ton of time examining why were sports fans. Most of us havent run cost-benefit analyses of being a sports fan as opposed to, say, getting into needlepoint or birdwatching. Sports are just something we like. Watching sports is just something we do. Being a sports fan is just something we are.

At root, fandom is about community and belonging. Bonding, even. Its about watching the games and the movies and reading the books, yes, but its also about talking about them, even hypothetically. Its about forming connections and forging a tribe of people with similar interests. When those people with similar interests come from disparate backgrounds, it can create an all-too-rare convergence of people who may otherwise never interact, and thats a very good thing.

There can be negatives to fandom, as anything driven by passion can be taken to negative extremes. The term fan itself likely comes from this sort of unhealthy connotation. Though the words origins are a little murky, etymologists tend to credit the nineteenth-century baseball manager and scout Ted Sullivan for the terms origin. Sullivan said in the 1890s that fan was short for fanatic, putting it in league with the terms crank and bug. Whether sports fandom brings positives or negatives, though, it is hard to escape the notion that sports fandom is, to a very large degree, driven by a certain irrationality and is often an emotional exercise.

Fandom and, more specifically, identification with a particular team, tends to be inherited. To the extent that psychologists have studied sports fandoma very, very small field of study, it should be notedthey have discovered, perhaps not surprisingly, that a majority of sports fans, usually around 60 percent, say that their introduction to sports came via a family member, more often than not through a father or father figure. For this reason, fandom is best thought of as an identity as opposed to an allegiance asserted by conscious choice. An identity that is bolstered by friendships, social encouragement, geography, and personal and cultural inertia. Watching games, following sports news, and finding a place in our minds and in our hearts for all that surrounds sports is just a thing we do because, for the most part, weve always done it, not because were making objective decisions on the matter.

In a 2018 study, researchers found that fans of sports teams and supporters of political parties perceive news in much the same way, with fans viewing news stories accusing their team of wrongdoingsuch as the violation of rules or engaging in sharp dealingsas biased regardless of the substance of the report. This operated in much the same way, researchers concluded, as reactions political partisans had to stories about their party in media outlets perceived to be hostile to their interests. They concluded that sports fans, like political partisans, filtered new information through the lens of group affiliation, relying on it as a mental shortcut to help make decisions. Once sports fandom had become a part of their identity, using their group identification to make judgments when faced with controversies became a powerful motivator. It often caused fans to interpret objective criticism of their favorite teams as a personal attack or to assume the mindset that their interests and the interests of the teams they root for are aligned when they really are not.

This book is about that placethe place where a fans interests and a teams interests diverge. It is about how sports teams and leagues, often in concert with political actors, the media, and business interests, which I collectively consider to be a kind of sports-industrial complex, can and do use our often irrational devotion and loyalty for their own purposes, and actively hurting the teams we love, the cities we call home, the athletes we cant stop watching. Sometimes, they even hinder the progress of social justice. This book is about how to identify those moments when the sports-industrial complex is working against our interests and what, if anything, we can do about it.

In politics, weve increasingly seen the idea that the scoreboard is all that matters. Winning elections is the ultimate objective for candidates as opposed to a means to the end of policy and the shaping of society. Weve likewise increasingly seen the notion that our team and the opposing team is the proper way to view the parties to the relevant contest. These concepts, which make sense to varying degrees in the context of sports, have been imported into politics and have served to degrade them.