This edition first published in hardcover in the United States and the

United Kingdom in 2013 by Overlook Duckworth, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

NEW YORK

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact sales@overlookny.com, or write us at the above address

LONDON

90-93 Cowcross Street

London EC1M 6BF

inquiries@duckworth-publishers.co.uk

www.ducknet.co.uk

Copyright 2013 by Eric Simons

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN: 978-1-4683-0758-0

Darwin Slept Here

F ROM THE BREAK OF THE HUDDLE TO THE BREAK OF THE heart takes about ten seconds. Ten: The twenty-year-old University of California quarterback Kevin Riley, our champion and savior in just his first collegiate game, emerges from amid his teammates and strides confidently to the line of scrimmage. Down by three points, fourteen seconds to go, no time-outs, twelve yards away from a glorious victory. Riley has played brilliantly in the debut performance of a lifetime. In the stands we are in love, swooning with expectant joy.

Nine: Fifty rows high in California Memorial Stadium I stand with my father, my companion at Cal football games since he hauled me out on his shoulders when I was four months old. My dad has been going to Cal games since his first year at Berkeley in 1971, when he went to watch a high school acquaintance play wide receiver. For thirty years hes had the same seats, section TT row 50, and now were looking almost directly down on the action.

Eight: Riley snaps the ball and drops back to pass. Everyone is standing. Everything: the hairs on my arms and neck are standing. It is absolutely crackling in the stadium, the greatest electrical storm any of us have ever experienced. My heart is pounding. It is a foggy, atmospheric October night in Berkeley. Sweat drips down my arms.

Seven: Riley scans the end zone, looking for the game-winning touchdown pass that will blow this crumbling old structure off its foundation. He may not know it, but up in the gallery were aware that hes probably looking at the greatest array of Cal offensive talent any of us will ever see, with seven future pros on offense alone.

Six: None of the big names appears to be open. Riley moves to his left. A low murmur rumbles forth from the fans. Throw the ball away.

Five: Even if we dont get the touchdown here, its okay. Riley will throw the ball away; well go to overtime. Surely, we cannot lose at home in overtime when we are the number-two-ranked team in the country and Oregon State is unranked. Its homecoming. The crowd is delirious after an inspired comeback. Number-one-ranked LSU has already lost. We will winwe will be fans of the number one team in college footballif we just get it to OT. None of us alive in this stadium has ever seen Cal ranked at the top in college football. Only a handful of us alive in this stadium have ever seen Cal win the Pacific-10 Conference and go to the hallowed Rose Bowl, which last happened in 1959. The schools last Rose Bowl victory was in 1938. We want this to happen so, so badly. It is a desire beyond longing, beyond lust, beyond addictive craving. Throw the ball away, Kevin. Lets go.

Four: Riley runs forward. He does not throw the ball away. I gasp. Seventy thousand people gasp. The Rubicon looms, beyond which he will either run for the winning touchdown or get tackled and force us to watch helplessly as time runs out. Throw the ball away!

Three: The die is cast. Riley is running. The collective inhalation of seventy thousand souls freezes the moment forever in our brains. None of us will ever forget this exact second of hopeless, helpless terror.

Two: Oregon State defenders swarm to Riley. He thrashes forward eight yards from the goal line. His knee hits the turf. The clock rolls.

One: Final score Oregon State 31, California 28.

Zero: The coach winds up and slams his headset into the grass. Seventy thousand stunned spectators stand silent. I teeter with hands on my head, my mouth agape, my soul on the rack.

An hour later Im riding the train from Berkeley back to my home in San Francisco. Its Saturday night and the train is full of people going out to the city, people dressed in sophisticated theater clothes, people headed to pleasant restaurants with linen tablecloths and Napa cabernet, people headed for swanky cocktails and cheery friends. Im slumping by myself, crammed defensively in the corner, feeling like absolute shit. My clothes are sweat-stained and reeking. My head aches from the constricting grasp of my faded Cal hat. For dinner I had a six-dollar steamed hot dog and a three-dollar bottle of water.

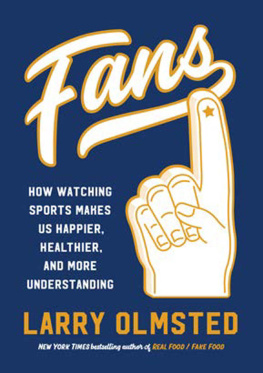

I describe this carefully because I think this sports experience was one of the most emotionally complicated moments of my life and it makes me more than a little curious about human biology to admit it. I think I had more of my brain active simultaneously in those ten seconds than I ever have in any other non-sporting circumstance. I say this, six years later and as soberly as I can, without judgment and certainly without pride. I loved my wedding. I loved being there for the birth of my daughter. Both were wonderful, rich, emotional occasions that Ill always cherish. Im just saying that diversity-of-feelings-wise, neither one held a candle to the raging pep-rally bonfire inside me on the night of October 13, 2007. And when you know that more than a billion people around the world can all say, Oh, dude, Ive sure been there before, youre no longer talking about some little quirk of human nature. Sports fandom appears to be a species-level design flaw.

In those ten seconds my hormone system blew up. My brain blew up. Neurons fired away like gangbusters in the brain centers for empathy, action, language, pride, identity, self, reward, relationships, love, addiction, perception, pain, and happiness. If youve seen those images at the end of heartbreaking games, where the fan is standing there with his hands on his head and his mouth yawningor if youve been that fanyou know that it feels like all this stuff is frothing around on the inside trying to beat its way out of your body like an alien chest-burster.

This book seeks to explain the science behind what actually happened to me in those few moments, and to explain why we feel the way we do about sports and why so many rational people follow them with such seemingly irrational passion. As human beings we come equipped with reflex responses to watching competition. But we also make a cultural choice to be sports fans, and from that choice a host of other related personal and societal consequences follows. Drawing from sciencemainly from fields far outside of sports psychologyas well as a bit of philosophy and sociology, the book answers the question of why we continue to make that choice even when the rewards often seem dubious. Watching sports is insanely complicatedand very personalbut underneath the layers of personality and culture lie the biological and psychological roots of a universal obsession.

WE TALK ABOUT SPORTS IN METAPHORS: AS WAR, AS LOVE, AS poetry, as ritual, as beastliness, as religion. It turns out that the quest to better understand those metaphors takes us to some delightful places. A lab in Portugal constructed a fish boxing-ring to learn about what happens to the testosterone of spectator fish. A researcher at Princeton created an elaborate ruse to get Yankees and Red Sox fans to lie in a brain scanner and revel in each others misery. Two endocrinologists in British Columbia designed their own game of competitive Tetris to see how aggressive people get when they win a video game. A relationship scientist in New York brought loving couples into his lab to test how much a lifetime of romance had made their brains think alike. A social psychologist in Scotland applied the lessons of soccer crowds to improve modern policing. A sociologist in the 1950s taught pigeons to lift their heads for a treat so that he could see how long it takes an animal to stop doing something when it stops getting a reward. Almost anything can help explain sports fandom, so thats what this book is about: weird creatures and strange behaviors found in the lab and in the bleachers. And I surely do not want to discount in any way the rare crossovers, like the man who has dressed in a gorilla suit for every Oakland Raiders game for the last sixteen years.