Table of Contents

For my parents

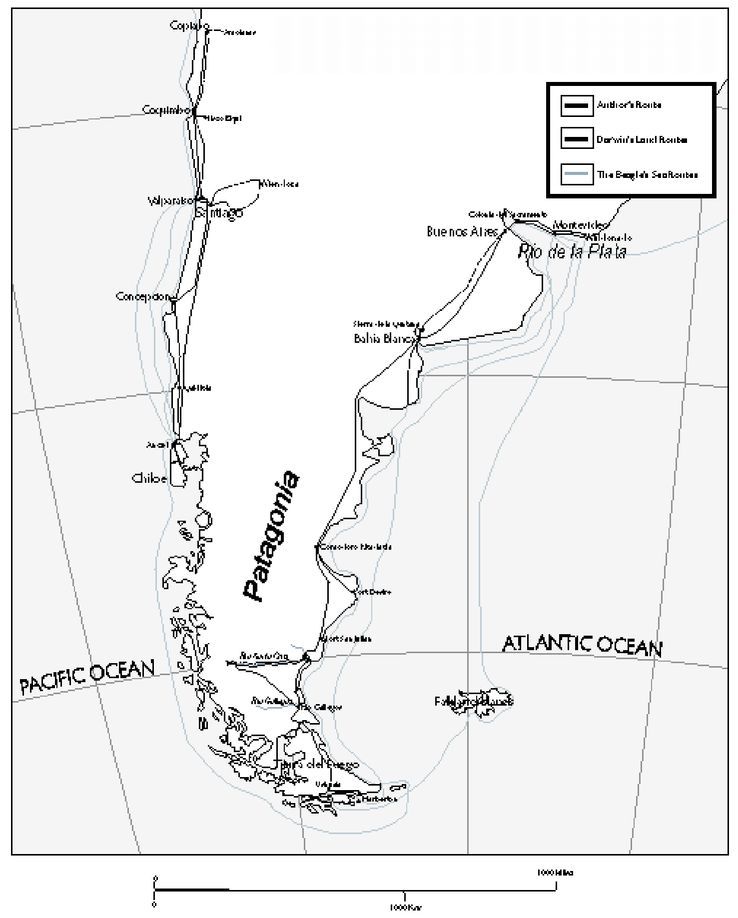

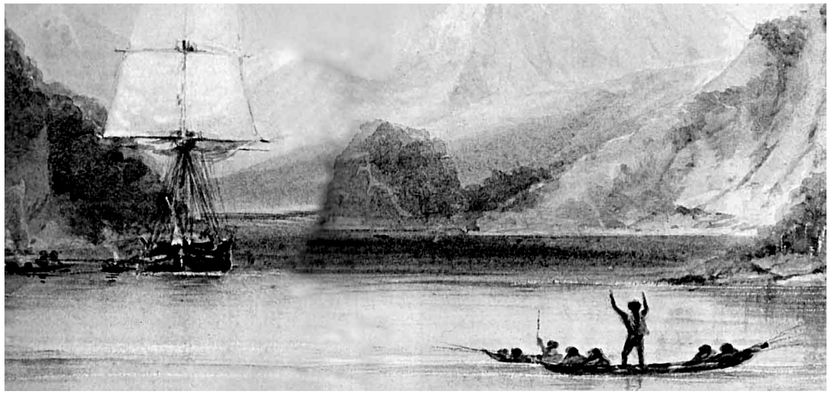

Following Darwin a Southern South America

INTRODUCTION

The Worlds Most Famous Iguana Hurler

Happiest at home with his notebooks and his microscopes.

INTRODUCTION TO AN EXHIBIT OF DARWIN ARTIFACTS NEW YORK MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY, MAY 2006

EVOLUTION HAD DONE THE THING RIGHT. The marine iguana of the Galapagos Islands swam well. Dined well. Lounged well. It basked in the sun, it munched seaweed, it strutted out for an occasional constitution-improving swim, all until one cloudless, sweltering September afternoon in 1835, when a young man stepped ashore and ruined everything.

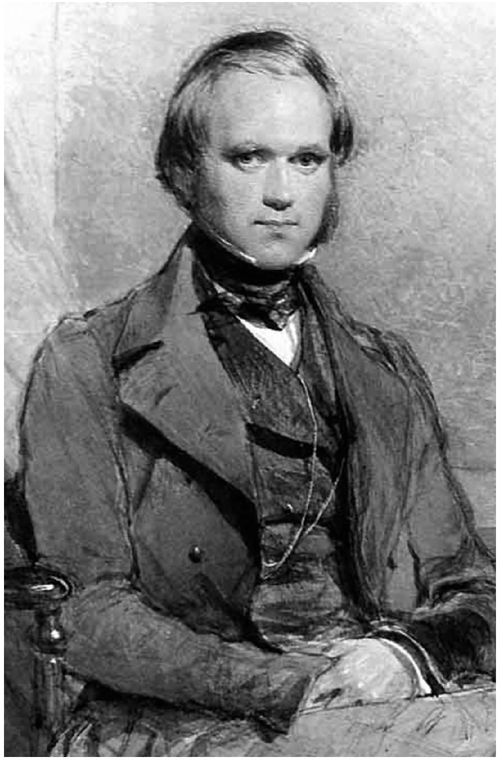

Charles Darwin had not yet conceived the theory of evolution by natural selection. Five months shy of his twenty-seventh birthday, tall and thin and already distinctively heavy browed, he had not yet acquired a reputation as a scientist, had not yet published a celebrated travelogue about South America (or an influential treatise on tropical corals), and had not yet had a species of ostrich named after him. His visit to the Galapagos came at the tail end of a five-year trip around the world, and it did not act on him as one of those Sistine-Chapel-ceiling, hand-meets-hand kind of moments. But Darwin was in the midst of a travel-induced transformation, combining his childhood love of exploration and biology with an increasingly sophisticated ability to catalogue nature. When he published The Origin of Species twenty-four years later, it was notable for the meticulous observational detail Darwin used to support his theory. For someone who delighted in scientific inquiry, the reptilian megafauna swarming the Galapagos was a scaly, ugly, crawlingand terrificlearning opportunity.

Darwin spent one day studying tortoises, chasing them, riding them, and upending them to see if they could right themselves. He spent another day with the marine iguanas, and it was not a good day to be a member of the lizard kingdom. He cut up the iguanas to see what they were eating (seaweed), and in his journal, he disparaged their color (dirty black), their disposition (stupid and sluggish), and their looks (hideous). He and a co-conspirator tied one animal to a rock and dropped it off their boat, the Beagle, to see what would happen (when, an hour afterwards, he drew up the line, it was quite active). He also noticed that some of the iguanas seemed to like the water, and he wondered: How well did they swim?

On the morning that Darwin chose to answer this question, it became evident that in one way, at least, evolution had failed the iguana: It had given it no recourse at all for dealing with thrill-seeking British naturalists. Darwin strode across the craggy rocks toward a napping imp of darkness, cornered it, snatched it by the tail, and hurled it into a pool left by the receding tide. The iguana, no doubt wondering what had gone wrong on a day that had started so pleasantly, swam straight back to its sunning rock.

Charles Darwin was a scientist at heart, and a good scientist always repeats his experiment. As the aggrieved beast climbed dripping from the pool, Darwin jumped forward again, clasped the iguana firmly in hand, and drew back. And then, in the name of science, discovery, and swimming iguanas, he hurled it into the sea.

In his five-year stint as geologist, naturalist, and traveler on the HMS Beagle, a gloriously happy Darwin galloped with Patagonian gauchos, stormed Montevideo armed with cutlasses and a knife between his teeth, beat his bare chest to properly greet an indigenous man in Tierra del Fuego, chased exotic birds, beetles, and butterflies through the jungles of Brazil, and, of course, took up iguana-tossing. He lived the swashbuckling explorer s life that modern travelers desire and almost never achieve, and he penned the book detailing the places and adventures that travelers hope to experience. A sense of exhilaration pervades The Voyage of the Beagleexhilaration totally dissonant with the Charles Darwin we remember today as a wrinkled, heavy-eyebrowed, white-bearded, finch-beak measurer. In the United States, at least, Darwin exists as an almost mythical figure: praised or reviled, overemphasized or over-criticized, beyond personality and beyond the affable cheeriness that defined most of his life. Critical creationists want to see Darwin as an old tormented evolutionist, unhappy with his work and shut up in his country house in England. Many evolutionists want to see him as a rigid scientist, a pristine visionary beyond the petty events of daily life. Biographers tend to approach the young, happy, excitable Darwin as merely a training ground for what would come later, picking apart his journals for clues to his thinking on evolution and discarding many of his early energetic adventures.

Darwin never forgot these experiences. The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career, he wrote in his autobiography. I feel sure that it was this training which has enabled me to do whatever I have done in science.

The science was pretty much the extent of what I knew until I happened across The Voyage of the Beagle for the first time, and read about the iguana-lobbing, and immediately went green with nineteenth century naturalist envy. The guy got to chase, catch, and throw iguanasrepeatedlyand call it research! But Id seen the pictures Darwin was some old tormented guy with facial fungus like Santa Claus. Well, how the hell did that happen?

My introductory encounter with The Voyage of the Beagle came in the late afternoon of a snowy day in Ushuaia, Argentina, the self-proclaimed southernmost city in the world. I was there in the very last days of a long trip, trying to put as much distance as possible between myself and a frustrating post-college stab at employment. Trying, in fact, to put seven thousand, one hundred, forty-three-point-four miles between usI really loathed that job. For two years Id worked the 4 P.M.-1 A.M. shift as a newspaper copy editorthe most soul-leeching job in an industry that operated on the principle that the more leeches dangling from employees the better. On nights when I couldnt indulge my primary form of relaxation (hurling dirt clods at the SLOW sign in the parking lot), I turned to a secondary method of stress relief: thumbing through the atlas. Retreating into the corner of my cubicle, I would dream of faraway lands, of reaching that glorious level of understanding where the Brazilian forest was more than little orange lines and squiggly blue rivers on a map, but a vast, green, three-dimensional place full of real people living real lives and chasing real lizards. So one miserable nightprobably as I was bumping the headline size on a car crash storyI bought plane tickets. Which was how I found myself a few months later, idling through my savings account in Tierra del Fuego, and stumbling into a bookstore that stocked English-language books on the same afternoon a pair of friends and I had bounded through snowy mountains overlooking the Beagle Channel. I decided on impulse to learn more about the ship that gave its name to the channel, and that provided Darwin with lodging for nearly five years. That evening I curled up in the hostel common room, watched snow swirling over the channel, and started to readand kept reading for the next two weeks as I stumbled back to Santiago, Chile, and returned home. But I could not leave that image of Darwin, and the snow falling over the Beagle Channel, behind. Back in California, with no burning ambition to return to graveyard-shift proofreading, I started to map out a new voyage.