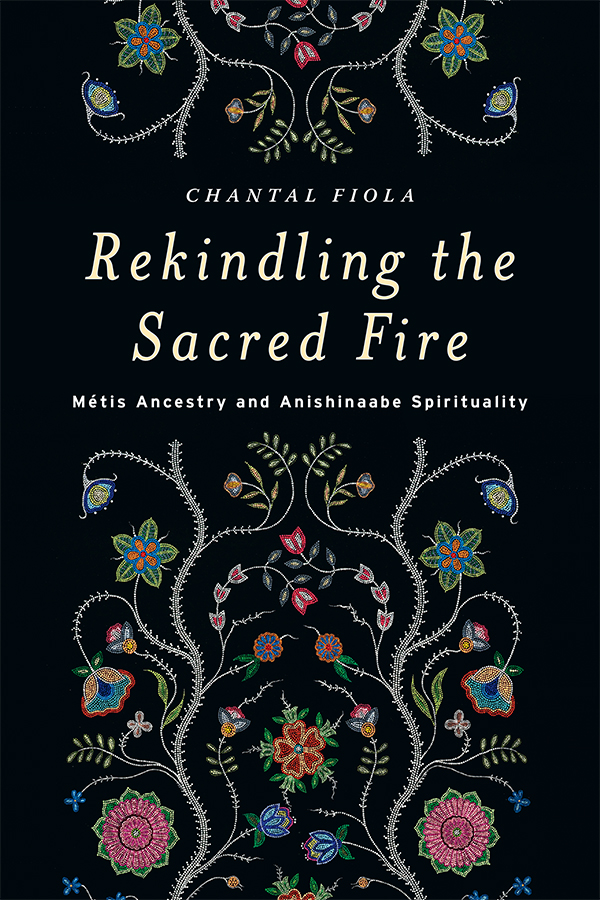

Rekindling the Sacred Fire

Mtis Ancestry and Anishinaabe Spirituality

CHANTAL FIOLA

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Canada R3T 2M5

uofmpress.ca

Chantal Fiola 2015

Printed in Canada

Text printed on chlorine-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper

19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the University of Manitoba Press, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca, or call 1-800-893-5777.

Cover image: Christi Belcourt, The Mtis and the Two Row Wampum (detail), acrylic on canvas, 48 x 72 in., 2002

Cover design: Frank Reimer

Interior design: Jess Koroscil

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Fiola, Chantal, 1982, author

Rekindling the sacred fire : Mtis ancestry and Anishinaabe spirituality / Chantal Fiola.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-88755-770-5 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-88755-478-0 (PDF e-book)

ISBN 978-0-88755-480-3 (epub)

1. MtisPrairie ProvincesRites and ceremonies. 2. MtisPrairie ProvincesReligion. 3. MtisPrairie ProvinceEthnic identity. 4. Mtis ColonizationPrairie Provinces. 5. Ojibwa IndiansPrairie Provinces Religion. 6. Ojibwa IndiansColonizationPrairie Provinces. 7. Prairie ProvincesEthnic relations. I. Title.

E99.M47F55 2015 971.200497

C2014-903277-3 C2014-903278-1

The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, Tourism, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

This book is dedicated to all the Mtis Anishinaabeg ancestors who worked tirelessly to ensure that we would still have our sacred teachings to guide us today. It is also dedicated to all those Mtis Anishinaabeg who are now rediscovering our rightful place in the sacred circle and picking up our work, and to all those Mtis Anishinaabeg who will come after us and continue this good work.

Contents

Note on Terminology

An indirect translation of Anishinaabe can be understood in English as the original people. I learned from Eddie Benton-Banai, Grand Chief of the Three Fires Midewiwin, that while the term Anishinaabe is often associated with Ojibwe/Saulteaux/Chippewa people, in its broader meaning it can encompass all Indigenous peoples and their spiritualities. My preference is to use the term Anishinaabe in this book; however, I sometimes use the terms Indigenous, Native, and Aboriginal interchangeably to mean Anishinaabe in its broader sense. As in the 1982 Constitution Act, I also use the term Aboriginal to refer to the First Nations, Mtis, and Inuit. As much as possible, I point out when I am using the more specific meaning of the term Anishinaabe (as belonging to the Ojibwe/Saulteaux/Chippewa cultures). Also, the double-vowel writing system for Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language) is used in this book except when referring to sources that use the phonetic system.

CHAPTER 1

Seven Fires Prophecy and the Mtis: An Introduction

Many years ago, seven prophets came to the Anishinaabeg. Each foretold a prediction of what the future would bring. Each prophecy was called a Fire, and each Fire referred to a particular era of time that would come in the future....

The first prophet said to the people, In the time of the First Fire, the Anishinaabe nation will rise up and follow the Sacred Shell of the Midewiwin Lodge. The Midewiwin Lodge will serve as a rallying point for the people and its traditional ways will be the source of much strength.

The Fourth Fire, given by two prophets who came as one, told of the coming of the Light-skinned Race. It was said that the future of our people will be known by the face of the Light-skinned Race. If they come wearing the face of brotherhood, there will follow a time of wonderful change and the two nations will join to make a mighty nation. But, if they come wearing the face of death, there will follow a time of great suffering.

The seventh prophet said to the people, In the time of the Seventh Fire an Osh-ki-bi-ma-di-zeeg (New People) will emerge. They will retrace their steps to find what was left by the trail. Their steps will take them to the elders who they will ask to guide them on their journey. The task of the New People will not be easy. If the New People will remain strong in their quest, the Waterdrum of the Midewiwin Lodge will again sound its voice. There will be a rebirth of the Anishinaabe nation and a rekindling of old flames. The Sacred Fire will again be lit.

It is at this time that the Light-skinned Race will be given a choice between two roads. If they choose the right road, then the Seventh Fire will light the Eighth and Final Firean eternal Fire of peace, love, brotherhood and sisterhood. If the Light-skinned Race makes the wrong choice of roads, then the destruction which they brought with them in coming to this country will come back to them and cause much suffering and death to all the Earths people.

Edward Benton-Banai, The Mishomis Book, 8993

The Seven Fires Prophecy (above) was given to the Anishinaabeg in the distant, pre-contact history by a series of prophets and triggered a great migration among the Anishinaabeg who would heed its warnings. Some Anishinaabe Elders believe that each of the fires (or eras of time) that were predicted has come to pass and that we are currently in the time of the Seventh Fire. They believe that the two paths mentioned in the Neesh-wa-swi ish-ko-day-kawn (Seven Fires Prophecy) are interpreted as the path of technology and the path of spiritualismthe former representing the rush to technological development (devoid of spirit) leading to destruction, and the latter representing the slower path of the traditional spirituality of our ancestors, which many are seeking anew and which does not lead to a scorched earth (Benton-Banai, 93). Our traditional teachers are encouraging us to recognize modern challenges to mino-bimaadiziwin (good, balanced life) and the ongoing importance of our ancestral ways of seeing, sometimes termed 360-degree vision, a holistic, interdependent world view (Dumont 1979, 11). A return to traditional spirituality among Anishinaabe people today represents one form of contemporary agency, as well as the unfolding of an ancient prophecy. As foretold in the prophecy, such a return is not easy.

Many Aboriginal families today, including Mtis people, are disconnected from our ancestral spiritual ways as a result of colonization. Mtis people have sometimes been referred to as the New Peoplefor instance, in Jacqueline Peterson and Jennifer Browns 1985 book, The New People: Being and Becoming Mtis in North America, which remains one of the most seminal academic sources on Mtis studies to date. It would likely come as a shock to many to learn that Louis Rielarguably the most famous Mtis leader, the Father of Manitoba and a devout Catholicwas, according to oral history, adopted by a Midewiwin family and became Midewiwin himself (Chapter 2). The Seventh Fire speaks of the importance of the work of the Oshkibimaadiziig as contributing to the potential for an Eighth (and final) Fire, an eternal fire of unity to be lit by all humans (Simpson 2008b, 14). Mtis people can contribute significantly to this work in contemporary times. Hence the title of this book; it refers to Mtis participation in the work of the Oshkibimaadiziig (rekindling our sacred ancestral ways) spoken of in the Seven Fires Prophecy.