A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book can trace its deepest origins back to the summer of 1998. I probably would have remained blissfully unaware of Harry Garfield and the Institute of Politics were it not for Cheryl Shanks, a new colleague in the political science department at Williams College. She told me that I should look into the history of the Institute, which she said played an important role in the development of international relations in the interwar era. Since I had never heard of the Institute and E. H. Carr never referred to it in The Twenty Years Crisis, I was very skeptical of the claim, but I went downstairs to the archives to find out for myself. It turned out that the Institute records at Williams were completely unprocessed and off limits to researchers, but a kind librarian mistakenly allowed me unfettered access to the entire collection, an error for which I will be eternally grateful.

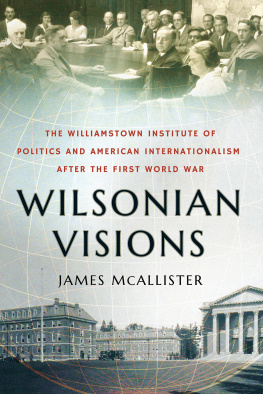

The debts that I have accumulated over the course of writing this book are substantial. The first round of appreciation must go to all of the archivists who have provided indispensable assistance and kindness. The biggest thanks go to Sylvia Brown and the wonderful staff at the Williams College archives. In addition to all of her work in making the Institute records and the Harry Garfield papers accessible to researchers, Sylvia played an invaluable role in helping find images for the book. I also need to thank Jennifer Comins at Columbia Universitys Rare Book and Manuscript Library for her assistance in locating materials related to the Institute in the records of the Carnegie Corporation.

I have had the remarkable good fortune to have Cornell University Press publish both of my books. In both cases, Robert Jervis played an indispensable role in the process. I will never forget his encouragement at a time when I was quite unsure if anyone would be interested in the Institute of Politics and the origins of postwar American internationalism. Roger Haydon provided equal doses of needed encouragement and tough love both times around. After Rogers retirement in September 2020, Michael McGandy played a crucial role in making it possible to publish the book in time for the centennial of the first session of the Institute in 2021. I would also like to thank Ellen Labbate, Susan Specter, and Mary Ribesky for all of the hard work they put in to the editing and production of the final version of the manuscript.

I was incredibly fortunate to have David Ekbladh and John A. Thompson as outside reviewers for this book. Their perceptive comments were greatly appreciated and resulted in a vastly improved final manuscript. Dusty Griffin, who has written a great deal about various aspects of the history of Williams College, generously read and commented on the entire manuscript within a few days of receiving it from me. Katie Sibley, who I had the great pleasure of working with on the State Departments Historical Advisory Committee, deserves special thanks for her comments on the manuscript. For his perceptive comments on the manuscript, as well as the model of his own scholarship, I would like to thank David Kaiser for all of his support.

I am especially grateful to all of my colleagues in the Department of Political Science at Williams College. I might have finished this book a few years earlier if I had spent less time discussing current political issues and college affairs with Justin Crowe, Galen Jackson, Darel Paul, Michael MacDonald, and Mason Williams, but I dont regret that tradeoff for a second. I also want to thank my departmental colleagues Sam Crane, Cathy Johnson, Jim Mahon, Mark Reinhardt, and Cheryl Shanks for putting up with me for so long. Finally, I owe a real debt to Sarah Campbell-Copp for all of the assistance she provided when I served as chair of the department. Special thanks also go to Paul MacDonald and Stacie Goddard, who for many years have been my partners in running the Summer Institute in American Foreign Policy program at Williams. Paul and Gordon's support has had a tremendous impact on the lives and career paths of countless Williams students over the last two decades.

Many students at Williams have provided invaluable research assistance on this book over the years. I thank all of them deeply, but a few students provided help that went above anything that I could reasonably expect. Emily Hertz spent an entire summer going through the voluminous scrapbook records of the Institute. Will Hayes did tremendous work documenting newspaper coverage of Harry Garfields service as Fuel Administrator. More recently, Asher Lasday, Gieben Na, and Zia Saylor have helped me in preparing the manuscript for publication. Zias superb efforts in helping prepare the index saved me a great deal of time and aggravation.

Finally, my extended family deserves recognition for all of the sacrifices they have made over the years that allowed me to finish this book. I thank Carrie, Catherine, and DJ for all of their love and support, as well as the encouragement I have always had from my parents, Maureen and Steve Tuck, and from my two sisters, Carol and Linda.

Introduction

A Wilsonian Life

European statesmen, Asiatic men of letters, South American Ambassadors are travelling from the uttermost parts of the earth toward a little village in the Berkshire foothills, where at the end of this month is to assemble a miniature Versaillesa Genoa, a Hague, a Lausanne, rolled into one.

Margaret de Forest Hicks, Nations Compare Notes under Berkshire Skies, New York Times, July 22, 1923

The little village in the Berkshire foothills is Williamstown, Massachusetts, home of Williams College since 1793. The physical beauty of the town and the surrounding mountains, as well as the isolation from the numerous distractions presented by a more urban environment, provides a nearly perfect setting for an elite liberal arts college. Henry David Thoreau, who traveled through the area in the summer of 1844, was memorably inspired by the sight of Williamstown as he stood at the top of Mount Greylock, the highest elevation in the state of Massachusetts. In words often quoted by Williams alumni, Thoreau proclaimed that it would be no small advantage if every college were thus located at the base of a mountain. Even though a few things have changed since Thoreaus visit, Williamstown remains the quintessential small New England village. The population is well below ten thousand people, and the town still gets by with a single traffic light. Relative isolation from the outside world continues to be one of the areas distinguishing features: students and faculty at Williams, most affectionately, still refer to Williamstown as the purple bubble and as a place where all world news is lost.