TO TURN THE WHOLE WORLD OVER

BLACK INTERNATIONALISM

Edited by Keisha N. Blain and Quito Swan

This series grapples with the international dimensions of the Black freedom struggle and the diverse ways people of African descent articulated global visions of freedom and forged transnational collaborations.

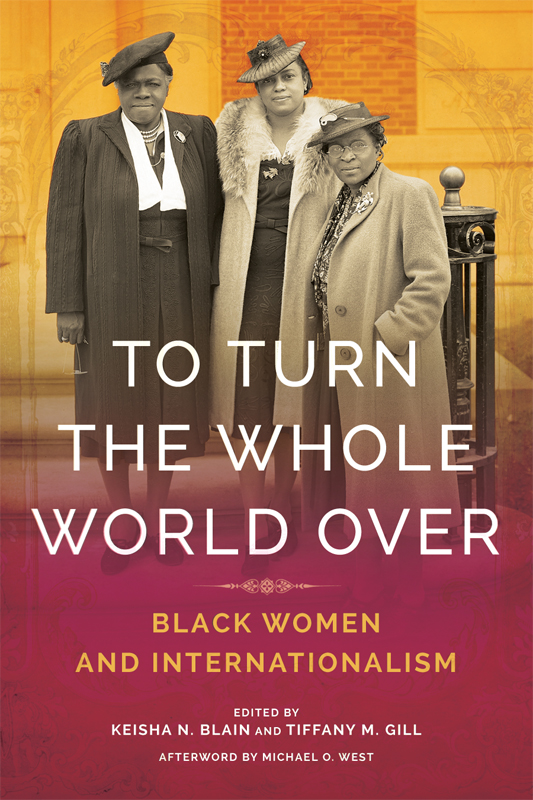

TO TURN THE

WHOLE WORLD OVER

Black Women and Internationalism

Edited by

KEISHA N. BLAIN AND

TIFFANY M. GILL

Afterword by Michael O. West

2019 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Publication of this book was supported by funding from the Cochran Scholar Fund.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Blain, Keisha N., 1985 editor. | Gill, Tiffany M., editor. | West, Michael O. (Michael Oliver), writer of afterword.

Title: To turn the whole world over : black women and internationalism / edited by Keisha N. Blain and Tiffany M. Gill ; afterword by Michael O. West.

Description: [Urbana, Illinois] : University of Illinois Press, [2019] | Series: Black internationalism | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018040431| ISBN 9780252042317 (hardcover ; alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252084119 (pbk. ; alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : African American womenPolitics and government19th century. | African American womenPolitics and government20th century. | African American women political activistsHistory19th century. | African American women political activistsHistory20th century. | InternationalismHistory19th century. | InternationalismHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC E 185.86 . T 6 2019 | DDC 305.48/896073009034dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018040431

E-book ISBN 978-0-252-05116-6

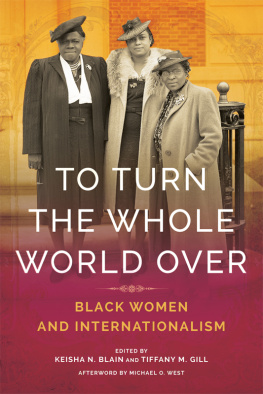

Cover image: Dr. Charlotte Brown, Mary McLeod Bethune, and an unidentified woman, 1942. (Scurlock Studio Records, ca. 19051994, Archives Center, National Museum of American History)

CONTENTS

| Keisha N. Blain and Tiffany M. Gill |

| Brandon R. Byrd |

| Annette K. Joseph-Gabriel |

| Kim Gallon |

| Tiffany N. Florvil |

| Anne Donlon |

| Nicole Anae |

| Stephanie Beck Cohen |

| Keisha N. Blain |

| Grace V. Leslie |

| Julia Erin Wood |

| Dayo F. Gore |

| Michael O. West |

INTRODUCTION

B LACK W OMEN AND THE C OMPLEXITIES OF I NTERNATIONALISM

Keisha N. Blain and Tiffany M. Gill

In 1927 Mary McLeod Bethune, renowned educator and black freedom advocate, boarded a ship to Europe. This was the first time this daughter of sharecroppers had ever left the United States. Her travel diary provides rich details of her impressions of the continentespecially its landscapes, architecture, and people. Bethune returned from her trip excited to share the news of her European adventures with those she encountered through her extensive work with black womens organizations and clubs. She admonished her organizational sisters to follow in her footsteps, claiming that traveling abroad was a way for black women to expand their understanding of the world beyond the United States and to make professional and political connections across the globe. Indeed, Bethunes four-month European excursion reaffirmed what she told the members of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) just one year earlier: that black women are not merely a national influence, but also a significant link between the peoples of color throughout the world.1 Among the women who caught Bethunes vision was beauty educator and entrepreneur Marjorie Stewart Joyner, leader of the United Beauty School Owners and Teachers Association, who planned to take a group of black beauticians to Europe in the 1930s. Joyner consulted extensively with Bethune while organizing the trip, and in one of their many sessions, Bethune proclaimed that if more black women embraced their vision, they could indeed turn the whole world over.2

To Turn the Whole World Over is the first scholarly attempt to assemble the most recent and innovative works on black womens internationalism. It highlights the range and complexity of black womens global engagements and centers their experiences as key historical actors in shaping internationalist movements and discourses from the 1870s to the present. By analyzing the gendered contours of black internationalism during this period, this collection of essays engages two key questions: How was black womens engagement in internationalism similar to or different from their male counterparts? And to what extent did black women merge internationalism with issues of womens rights and feminist concerns? The anthology also calls for a reconceptualization of black internationalism by asking how black womens lives and experiences alter the ways narratives of the global black freedom struggle are articulated. This anthology, then, does more than expand the paucity of scholarship on black women and internationalism. Indeed, this volume is both an assessment of the field as well as an attempt to expand the contours of black internationalism theoretically, spatially, and temporally.

Interventions

The rich and robust scholarship on black internationalism focuses on the global visions of black people in the United States and other parts of the African diaspora. It captures their sustained efforts to forge transnational and transracial collaborations and solidarities with people of color from various parts of the globe. More specifically, black internationalism is framed within most historical scholarship as a global political, intellectual, and artistic movement of African-descended people engaged in a collective struggle to overthrow global white supremacy in its many forms.3 As scholars have shown, this global racial consciousness is by no means static or monolithic. Historically, it has taken on various manifestations and been called by many names.4 In 1928 Afro-Martiniquean intellectual Jeanne Jane Nardal published her classic essay, Internationalism noir (Black internationalism), in La Despeche africaine a magazine cofounded and edited by her sister Paulette Nardal. In this groundbreaking essay, Jane called for the cultural rise of Afro-Latin and Francophone New Negro artists and writers across the globe.5 Inspired by the New Negro movement of the period, she argued that this new generation of black men and women would study the history of the black race. With time, Nardals black internationalism would come to signify much more than the study of the black race. By the mid-1940s, black activists, scholars, and intellectuals across the globe began to use the term in far more expansive waysas an insurgent political culture emerging in response to slavery, colonialism, and imperialism; to describe the political and cultural ways in which black communities collectively raised questions of struggle and liberation on a global scale; and to capture the various ways black people built relationships with other communities across the globe. Even before the term became used in common parlance, numerous writers, including Merze Tate, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Kwame Nkrumah, engaged black internationalism as an idea through various lenses including Pan-Africanism and communism.6

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.