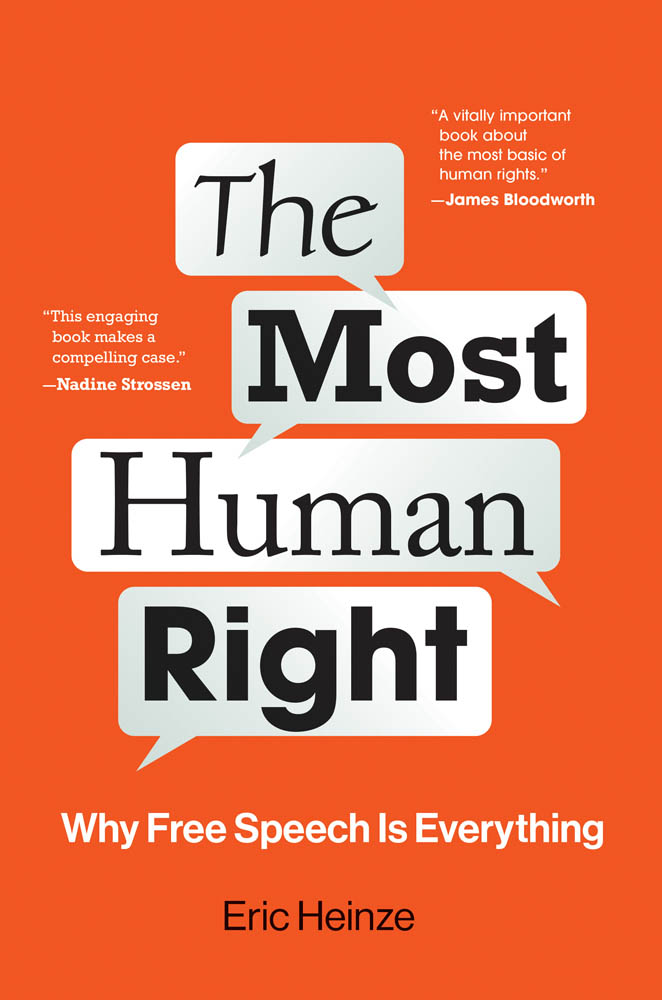

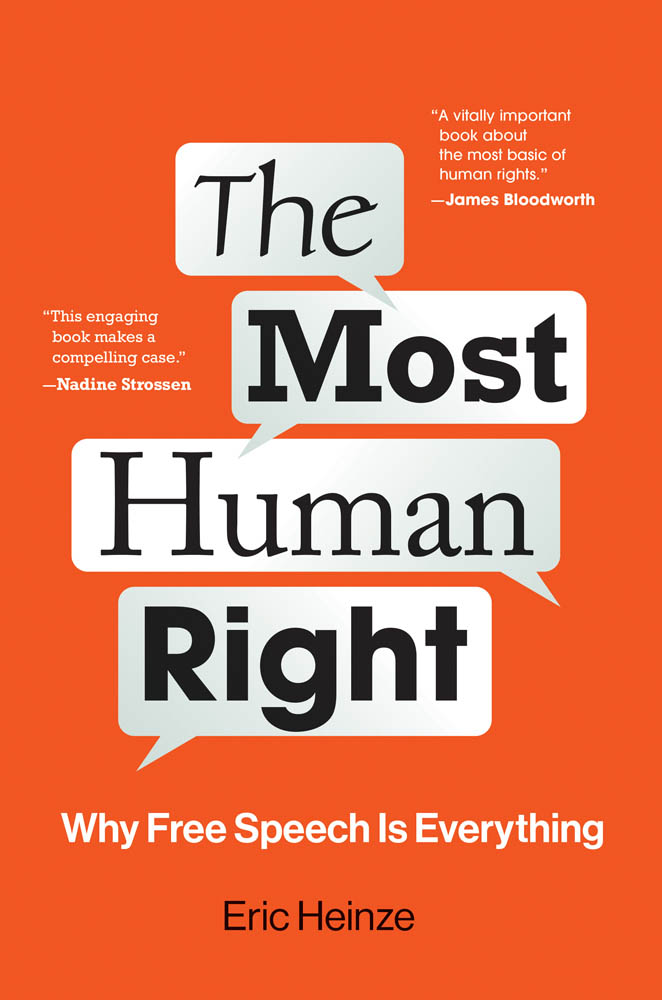

The Most Human Right

The Most Human Right

Why Free Speech Is Everything

Eric Heinze

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Eric Heinze

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the author.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Heinze, Eric, author.

Title: The most human right : why free speech is everything / Eric Heinze.

Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021010581 | ISBN 9780262046459 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Freedom of speech. | Civil rights. | Human rights.

Classification: LCC K3254 .H45 2022 | DDC 342.08/53dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021010581

d_r0

To Henry Steinerwithout his initiation into human rights this book could not have been written.

The true goal of politics is not merely the least worst administration of the public good.

Pierre Viansson-Pont

Contents

In 2005 Rakhmonberdi Ernazarov was imprisoned in Kyrgyzstan, accused of raping his former girlfriends father. He was confined along with six other men to a cell measuring thirty square feet. Ernazarov was denied visits from his family and was seen by a lawyer only once. After a few weeks he was found dead from cuts to his body.

In the autopsy report, Ernazarovs death was recorded as a suicide, but his brother Mamatkarim had doubts. A prison guard told the familys lawyer that Ernazarov had been subjected to constant insults after cellmates heard about the charge of sexually assaulting another man. The guard claimed that Ernazarov had been forced to eat and sleep near the toilet, that his dish and spoon had been damaged by his cellmates to make it difficult for him to eat, and that he had been forced to inflict injuries upon himself with metal cutlery. According to Mamatkarim, the prison guards had known about the abuse but failed to prevent it. The Boston-based organization Physicians for Human Rights later cast doubt on the verdict that Ernazarov had taken his own life.

In another case, from 1998, an illiterate Iraqi, named Q to protect his identity, had fled Saddam Husseins regime to seek humanitarian protection in Denmark. Danish authorities issued residency permits to him and his family. Medical examinations later confirmed that he had been tortured and suffered from ongoing physical and emotional trauma. In 2005, Q applied for Danish citizenship but was turned down for failing to complete his training in Danish culture and language. Under national guidelines, both physically and mentally disabled applicants could be excused from the language requirement, but those rules did not include individuals suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Denmark rejected Qs application, leaving him uncertain about where he and his family would live.

Finally, consider the case of Alexander Kazulin, a former rector of the Belarusian State University and Deputy Minister of Education. In March 2005, Kazulin became chairman of the Belarusian Social Democratic Party. The following year he ran for president of Belarus, publicly condemning the dictatorship headed by Alexander Lukashenko since 1994. In the run-up to the March 2006 election, Kazulin was attending the national legislature as one of his partys representatives when unknown agents beat him, then tossed him into a police van. He was forced to sit between the seats with his legs against his head, choking on his own blood.

Later that month Kazulin took part in a national Freedom Day assembly in the capital Minsk, marching with others toward a jail in support of political prisoners being held there. Soldiers sought to disperse the crowd with batons, smoke bombs, and sound grenades. Kazulin was again beaten by officers and subsequently charged with hooliganism and public order offenses. After a flawed trial he was sentenced to five-and-a-half years in a penal colony, living in substandard conditions and denied basic medical care as well as contact with lawyers or with family and friends.

These cases were all examined by the United Nations Human Rights Committee, one of several international bodies charged with monitoring how governments treat their citizens. The committee concluded that Kyrgyzstan, Denmark, and Belarus had violated the three mens human rights.

Conflicts Old and New

In one sense, such conflicts are as old as humanity itself. From time immemorial governments have abused their powers. Ancient belief systems responded by holding rulers to high standards of justice. Over two thousand years ago, Confucius (ca. 551479 BCE) sought to explain that government must follow principles of righteousness (y, ) and integrity (xn (). He encouraged officials to observe rn (or jn, ), by acting in benevolent and humane ways.

Yet in another sense, Ernazarov, Q, and Kazulins stories are very new. Traditionally the relationship between a government and its population had been viewed as a domestic matter. I shall frequently mention that document, so you will find a copy in this books appendix.

The Universal Declaration states essential principles in simple language. For example, according to Article 5: No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. According to Article 7: All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination. To be sure, the more we contemplate even those two seemingly easy articles, the more complex they become. Does it count as slavery when people are so poor and wages so low that workers end up beholden to unscrupulous employers? Is it true that All are equal before the law if the wealthy can afford better legal services than the poor, or if mens courtroom testimony carries greater weight than womens?

For some people, those types of questions reveal deep flaws in the idea of human rights. Human rights, they argue, are framed in open-ended language, and can say whatever you want them to say. Nothing in the concept of a right per se rendered one interpretation self-evident and the other unthinkable. Could it be that the malleability of rights, the possibility of interpreting their broad language in conflicting ways, precludes the possibility of human rights having any reliable meaning?

Not at all. The rights set forth in the Universal Declaration are no more or less pliable than the types of norms we would find in many justice systems. Justice systems throughout history have relied upon values conceived in general terms that can be interpreted in conflicting ways, such as fairness, reasonableness, respect, dignity, honor, decency, utility, prudence, welfare, necessity, progress, rationality, public interest, collective good, or righteousness. Here are some easy examples. We read that one of Confuciuss disciples asked how to serve ones ruler. Confucius responded, Do not deceive him, and only then will you be able to confront him directly [and deliver your admonishment]. Yet hasnt acquiescence led to regimes that killed and brutalized millions?

Next page