Copyright 2022 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-64421-121-2

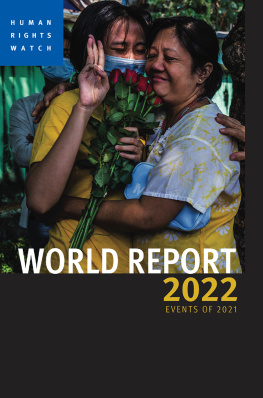

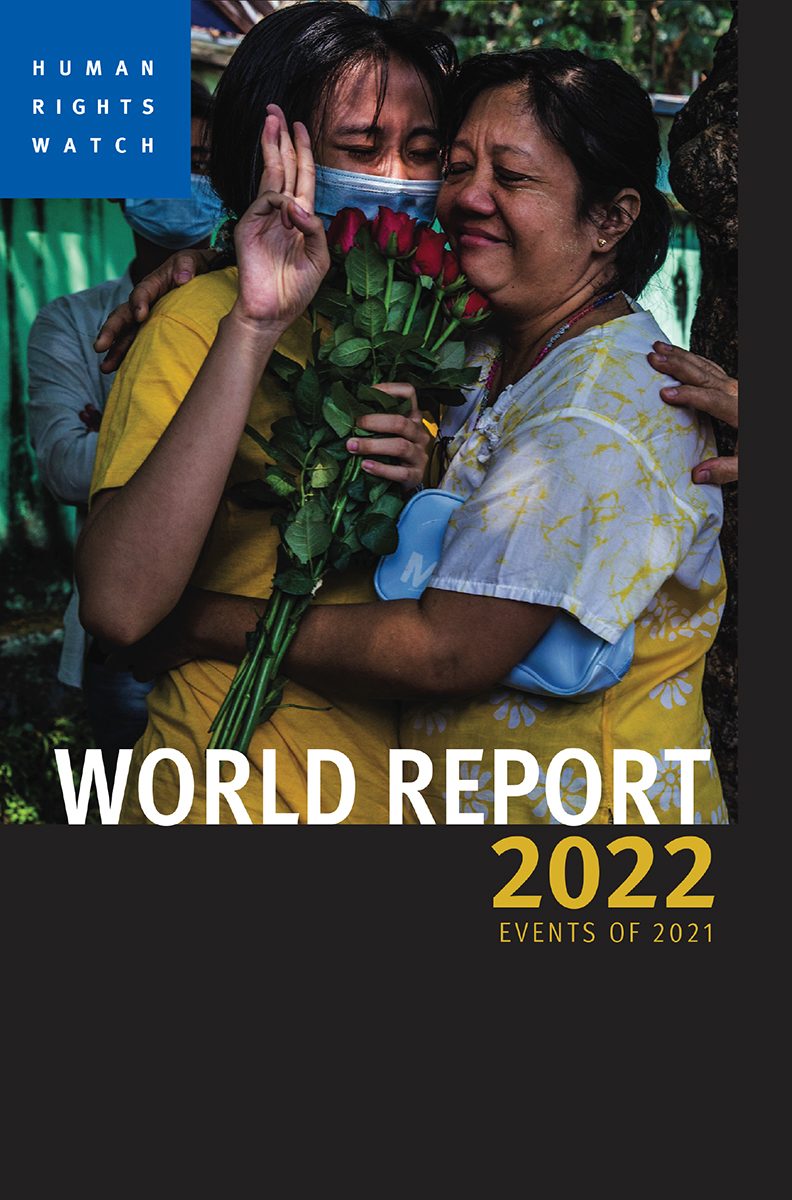

Cover photo: A protester released from prison after three weeks of detention is reunited with her mother in Yangon, Myanmar, March 24, 2021. The three-finger salute, adapted from The Hunger Games, is a widely used sign of civil disobedience.

2021 The New York Times/Redux.

Cover and book design by Rafael Jimnez

www.hrw.org

Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide.

We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice.

Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all.

Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Europe and Central Asia division (then known as Helsinki Watch). Today it also includes divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and the United States. There are thematic divisions or programs on arms; business and human rights; childrens rights; crisis and conflict; disability rights; the environment and human rights; international justice; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender rights; refugee rights; and womens rights.

The organization maintains offices in Amman, Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Bishkek, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Hong Kong, Johannesburg, Kiev, Kinshasa, London, Los Angeles, Miami, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, So Paulo, Seoul, Silicon Valley, Stockholm, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich, and field presences in more than 50 other locations globally.

Human Rights Watch is an independent, nongovernmental organization, supported by contributions from private individuals and foundations worldwide. It accepts no government funds, directly or indirectly.

Table of Contents

COUNTRIES

This annual World Report is dedicated to the memory of our beloved colleague Dewa Mavhinga, Southern Africa director at Human Rights Watch, who died on December 4, aged 42. Dewa was a respected and principled human rights researcher, a fearless advocate and an indefatigable champion for human rights victims across Southern Africa. Colleagues and partners remember him for his unwavering dedication and depth of knowledge, but most of all for his warmth, generosity and unfailing kindness.

With Autocrats on the Defensive, Can Democrats Rise to the Occasion?

By Kenneth Roth,Executive Director

The conventional wisdom these days is that autocracy is ascendent, democracy on the decline. That view gains currency from the intensifying crackdown on opposition voices in China, Russia, Belarus, Myanmar, Turkey, Thailand, Egypt, Uganda, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. It finds support in military takeovers in Myanmar, Sudan, Mali, and Guinea, and undemocratic transfers of power in Tunisia and Chad. And it gains sustenance from the emergence of leaders with autocratic tendencies in once- or still-established democracies such as Hungary, Poland, Brazil, El Salvador, India, the Philippines, and, until a year ago, the United States.

But the superficial appeal of the rise-of-autocracy thesis belies a more complex realityand a bleaker future for autocrats. As people see that unaccountable rulers inevitably prioritize their own interests over the publics, the popular demand for rights-respecting democracy often remains strong. In country after country, large numbers of people have recently taken to the streets, even at the risk of being arrested or shot. There are few rallies for autocratic rule.

In some countries ruled by autocrats that retain at least a semblance of democratic elections, opposition political parties have begun to paper over their policy differences to build alliances in pursuit of their common interest in ousting the autocrat. And as autocrats can no longer rely on subtly manipulated elections to preserve power, a growing number are resorting to overt electoral charades that guarantee their desired result but confer none of the legitimacy sought from holding an election.

Yet, autocrats are enjoying their moment in the sun in part because of the failings of democratic leaders. Democracy may be the least bad form of governance, as Winston Churchill observed, because the electorate can vote the government out, but todays democratic leaders are not meeting the challenges before them. Whether it is the climate crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic, poverty and inequality, racial injustice, or the threats from modern technology, these leaders are often too mired in partisan battles and short-term preoccupations to address these problems effectively. Some populist politicians try to divert attention with racist, sexist, xenophobic or homophobic appeals, leaving real solutions elusive.

If democracies are to prevail in the global contest with autocracy, their leaders must do more than spotlight the autocrats inevitable shortcomings. They need to make a stronger, positive case for democratic rule. That means doing a better job of meeting national and global challengesof making sure that democracy delivers on its promised dividends. It means standing up for democratic institutions such as independent courts, free media, robust legislatures, and vibrant civil societies even when that brings unwelcome scrutiny or challenges to executive policies. And it demands elevating public discourse rather than stoking our worst sentiments, acting on democratic principles rather than merely voicing them, unifying us before looming threats rather than dividing us in the quest for another do-nothing term in office.

Most of the world today looks to democratic leaders to solve our biggest problems. The Chinese and Russian leaders did not even bother showing up at the climate summit in Glasgow. But if democratic officials continue to fail us, if they are unable to summon the visionary leadership that this demanding era requires, they risk fueling the frustration and despair that are fertile ground for the autocrats.

The Perils of Unaccountable Autocrats

The first goal of most autocrats is to chip away at the checks and balances on their authority. Democracy worthy of its name requires not only periodic elections but also free public debate, a healthy civil society, competitive political parties, and an independent judiciary capable of defending individual rights and holding officials to the rule of law. As if autocrats all read from the same playbook, they inevitably attack these restraints on their powerindependent journalists, activists, judges, politicians, and human rights defenders. The importance of these checks and balances was visible in the United States where they impeded President Donald Trumps attempt to steal the 2020 election, and in Brazil where they are already working to impede President Jair Bolsonaros threat to do the same in the election scheduled for 2022.