Published in 2000 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Text copyright 2000 by Ian Barnes

Maps and design 2000 by Arcadia Editions Limited

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Routledge, Inc. respects international copyright laws. Any omissions or oversights in the acknowledgments section of this volume are purely unintentional.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barnes, Ian, 1946

The historical atlas of the American Revolution / Ian Barnes; Charles Royster, consulting editor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-92243-7 (alk. paper)

1. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783. 2. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783Maps. I. Royster, Charles. II. Title.

E208 B36 2000

973.3dc21

99-059920

Many writers have reminded us that the War of American Independenceknown in Britain at that time as the American Warwas not the same as the American Revolution. The revolution entailed innovations in government and new political ideas and institutions changing the role of the citizen, the nature of legislative representation, the power of the executive, and the relations between national and local governments. The war, on the other hand, was waged in a manner readily recognizable to veterans of previous conflicts, especially the Seven Years War, which began twenty years earlier. The War of American Independence was not revolutionary in military ideas or practice.

In the Seven Years War, Britain had dismantled much of Frances overseas empire. In the War of American Independence, France, by allying with the Americans, took its revenge, though at a heavy cost, which brought unexpected consequences upon the old regime. Americans, proud of their dedication to republicanism and liberty, nevertheless needed the army, the navy, the munitions, and the money of King Louis XVI in order to win independence from King George III. Americans claimed to have created a new kind of soldier for a new kind of war: a patriot, not a hireling, a thinking fighter, not an automaton. Yet the successes of George Washingtons Continental Army depended in large part upon his efforts to make it as reliable as the disciplined regular forces of European monarchs.

The War of American Independence lasted more than eight years, from the first shots in Massachusetts to the treaty of peace in France. The British cabinet led by Frederick North did not mount a sustained offensive for the duration of the war. At one time or another, British forces occupied every significant American city, but 95 percent of Americans did not live in cities, and their resistance, though fluctuating in its scale of effort, continued. The British tried first to isolate a supposed minority of rebellious agitators in the northeast. Then they tried to rally a supposed majority of loyal subjects in other parts of the continent. Neither effort succeeded because both were based upon false assumptions. The Royal Army and Navy repeatedly defeated the American forces or drove them to retreat. Yet these victories did not conquer a continent. And the crucial British defeatsTrenton, New Jersey, at the end of 1776, Saratoga, New York, in the autumn of 1777, and Yorktown, Virginia, in the autumn of 1781thwarted major offensives and, in the last two cases, lost entire British armies. The North administration took Britain more and more deeply into debt with fewer and fewer successes to justify these large expenditures. At last, North lost his majority in the House of Commons, and George III acknowledged in December 1782 that the treaty of peace must recognize the independence of the United States.

The American Revolution depicted and summarized by this historical atlas was, we can see, more than the military engagements of the War of American Independence. To understand that war and its outcome, the reader needs to know not only the dispositions of forces and materiel in combat, but also the motives underlying Americans effort to win independence and the difficulties inherent in the North administrations attempt to compel thirteen colonies to remain within the British Empire. For that reason, this historical atlas adopts a wide-ranging approach to its subject and strives to be as comprehensive as possible within the limits of its length.

It begins with a portrait of British North America and with the rivalry between Britain and France for control of North America. And it carries the story of American Independence into the first half of the nineteenth century. The revolution did not end with the departure of British troops. Americans had not yet fully agreed upon what kind of country they had created. Was its federal government perpetual and supreme or temporary and contingent? Would the nation continue human slavery indefinitely or confine and end it? Americans failed to resolve these questions through the mechanism of republican self-government which they so proudly created during the American Revolution. Instead, they found themselves fighting another warthis time not against British enemies but against one another.

The War of American Independence consisted not only of armies campaigns and naval engagements but also of a transatlantic struggle over trade and supplies. American privateering vessels and, eventually, the navies of France and Spain disrupted Britains commerce and supply lives. The British Navy tried to impede the flow of munitions and other goods from Europe to the Americans, by way of islands in the Caribbean. The armies fighting in North America were parts of vast and complex networks of logistics which made the Atlantic Ocean both a highway and a battlefield. In this contest, Britain failed. Americans kept their armies in the field until the North administration abandoned its effort to defeat rebellion.

The historical atlas which places the American Revolution in its broadest contextchronologically, geographically, culturallybest serves those readers seeking an introduction to the history of the period and those who use the atlas as a work of reference.

Professor Charles Royster

Louisiana State University

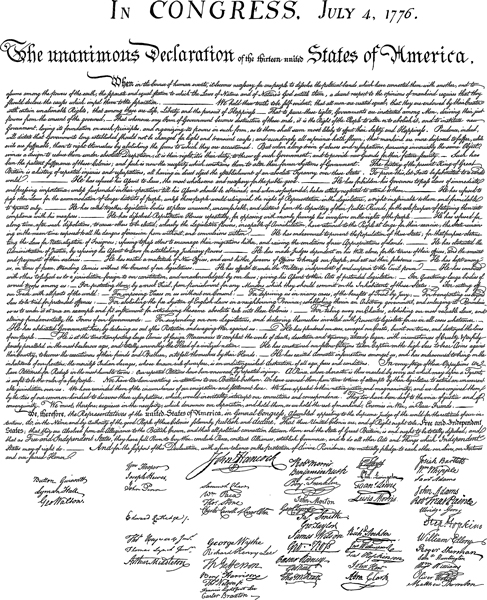

To celebrate Thanksgiving and the Fourth of July is to commemorate, first, the survival of a new society built upon the Mayflower Compact, an early form of the social contract and a social and political innovation. Second, the Declaration of Independence set in motion events leading to the 1787 Constitution, a document rooted in the Enlightenment with a separation of powers between the executive, legislative, and judiciary. Inspired in part by Montesquieus