Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

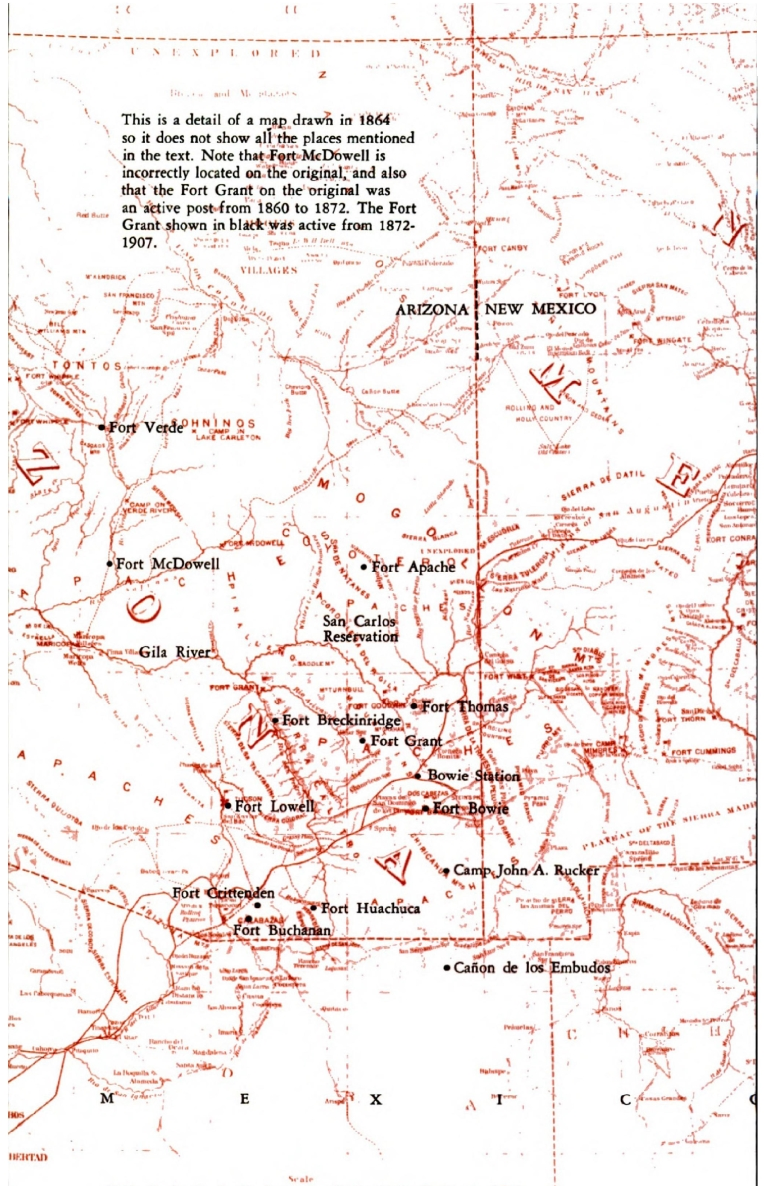

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

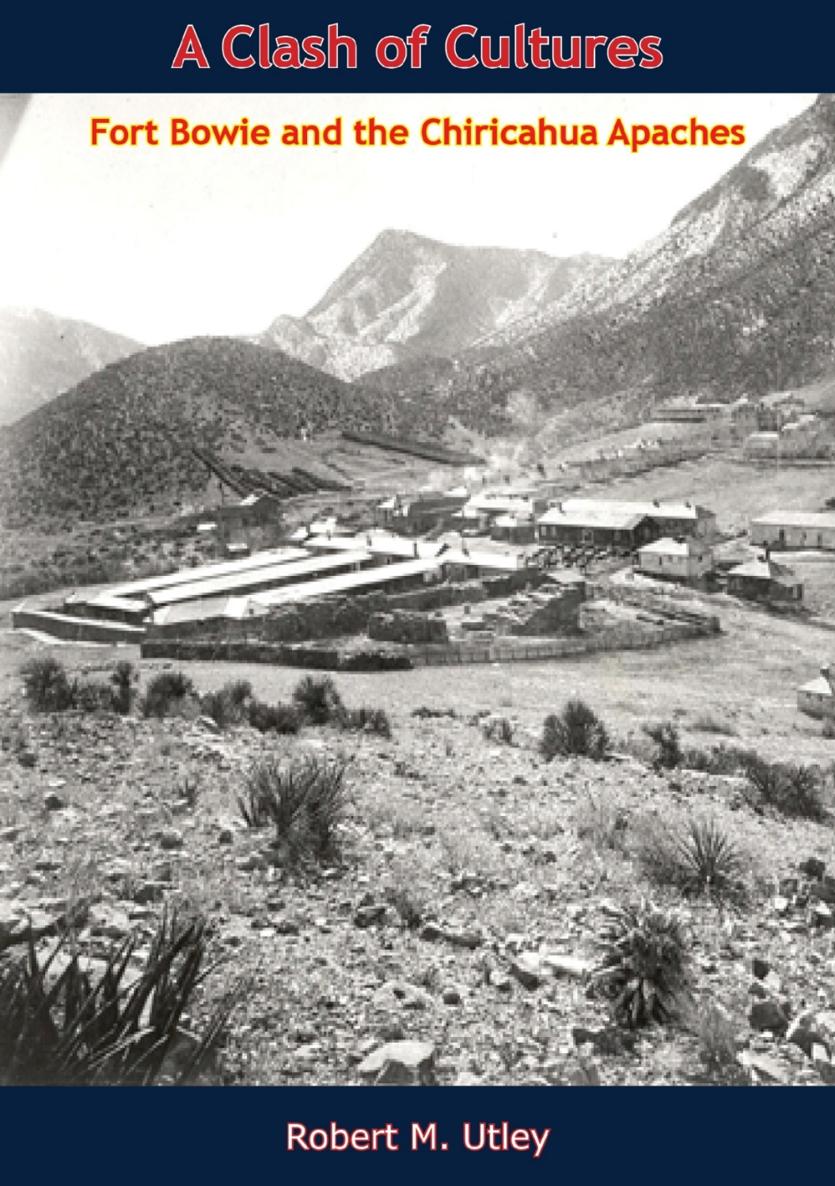

A CLASH OF CULTURES

FORT BOWIE AND THE CHIRICAHUA APACHES

BY

ROBERT M. UTLEY

Preface

On September 8, 1886, soldiers and Indians gathered on the parade ground of a frontier post nestled amid cactus-studded hills. A cordon of blueclad troopers formed around a train of open wagons loaded with Indian families. As a military band drawn up at the base of the flagstaff played Auld Lang Syne, the procession moved out of the fort and headed north.

The post was Fort Bowie, Arizona, for a quarter of a century a lonely bastion in Apache Pass, the heart of Apacheria. The Indians were Geronimo and his band of Chiricahua Apaches, for more than a decade scourges of the southwestern frontier. Now the warfare had ended, and with a touch of musical irony the victors bade farewell as the vanquished were escorted to the railroad cars that would bear them eastward to an uncertain future.

Today the gaunt ruins of Fort Bowie, set in an environment otherwise uncluttered by mans works, recall a dramatic and significant phase of the American pastthe struggle of a dynamic and aggressive people to conquer the wilderness, and the struggle of a proud and independent people to retain the wilderness and the way of life they had known.

The Land and the People

The Apaches originally lived in the Great Plains, but in the 16 th century they began to drift westward. Two hundred years later they had spread into the desert-and-mountain country we know as the American Southwest and had claimed Apache Pass as their owna long time before white men gave it the name it bears today. The dry, sun-baked tangle of rocky slopes and gullies supporting a profusion of vegetation equipped with thorns and other armaments called for a sturdy people, and that the Apaches were; the people and the land complemented each other.

The Apaches move westward coincided with the northward thrust of Spanish conquistadors from Mexico. By the 1700s, when the Apaches finally reached the limits of their migration, Spain had held the Rio Grande Valley for 100 years.

Like the rivers and mountains of their new homeland, the various Apache groups came to be known by names the Spaniards gave them. The Indians of Apache Pass were Chiricahuas. One of three Chiricahua groups, they roamed over much of what is now southeastern Arizona. Another band, usually called Warm Springs or Mimbres, lived to the east, among forested mountains near the Rio Grande. A third group, the Nednhis, emerged in the 1800s after some Chiricahuas took refuge in the towering wilderness of Mexicos Sierra Madre, to the south. Altogether, the Eastern, Central, and Southern Chiricahua probably numbered 1,000 to 2,000 people.

The total Apache population in the middle 1500s stood at about 8,000. On the west and northwest of the Chiricahuas were Pinals and Aravaipas. To the north lived the powerful Coyotero, or White Mountain, Apaches. Jicarillas inhabited mountains in northern New Mexico, north and east of the Spanish settlements of Santa Fe and Taos. Mescaleros occupied the Sierra Blanca and Sacramento Mountains of southern New Mexico and extended southward into Texas and Mexico.

The Chiricahua Mountains formed the homeland of the Central Chiricahua group. Trending from southeast to northwest, the mountains rise 1,000 meters {1} above the surrounding countryside. Pine and spruce fir forests cover the heights, while scrub oak and desert plants such as mesquite, agave, yucca, ocotillo, prickly pear, and various other cacti grow on the lower slopes. On both flanks rocky canyons plunge precipitously to the desert floor. A great stone promontory crowns the range. Viewed from a distance, it suggests a masculine face upturned to the sky and has been named Cochise Head, in honor of the Chiricahuas greatest chief. Nearby is a dazzling geological display known as the wonderland of rocks, now set aside as Chiricahua National Monument. Beyond the richly grassed Sulphur Springs Valley, 48 kilometers to the west, lie the Dragoon Mountains, also a favored Chiricahua haunt and site of another rocky fantasyland, called Cochises Stronghold. Visible across the barren trough of the San Simon Valley, 32 kilometers east, lie the Peloncillo Mountains and the borders of the Eastern Chiricahua domain.

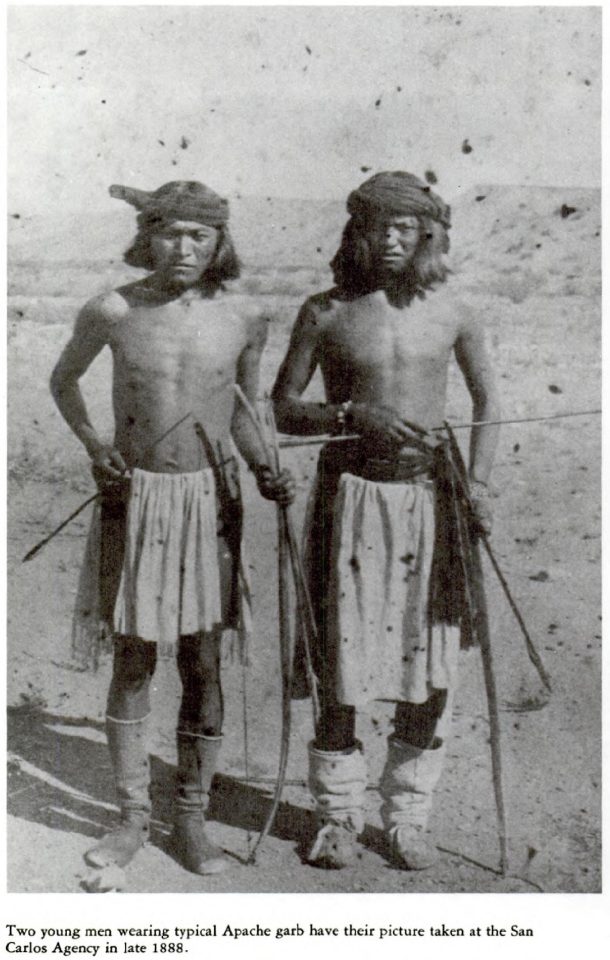

The Chiricahuas blended easily into this harsh land and made it support a satisfying if sometimes precarious way of life. In family bands of a dozen or more people, they moved constantly about their homeland in a perennial quest for food and as a defense measure. Although traveling in small groups, usually on foot, they could swiftly unite in larger gatherings for ceremonies or war. Dome-shaped dwellings of thatched beargrass laid on a framework of upright posts joined with willow branches, called wickiups, provided shelter. Furnishings included beds of grass and skins, woven baskets, skin containers, and utensils fashioned from bone, stone, and wood. Men wore buckskin shirts and long loincloths belted at the waist; two-piece buckskin dresses made up the womans outfit. All sported sturdy high-topped moccasins. Thick, shoulder-length black hair and a headband instantly identified the wearer as Apache.

The land usually yielded enough food. Men hunted deer and small game, and stole horses, mules, sheep, and cattle from Mexicans and, later, from Americans. Women gathered desert foodsyucca stems, agave heads, cactus fruit, pion nuts, berries, sunflower and other seeds, and mesquite beans. Sometimes the Chiricahuas planted corn, beans, and squash, but their nomadic habits made agriculture a minor occupation. Corn formed the base for tiswin, a weak beer of which they were very fond. Fermented mescal produced another popular beverage.